To be included on this list, the birth control had to be at least plausibly effective to some degree. Records exist of women in ancient Rome and Greece relying on dances and amulets to prevent pregnancy, and we can safely assume that those probably didn’t do much. At the risk of stirring up controversy, I’ve listed both contraceptives—which prevent sperm from fertilizing egg—and abortifacients, which induce abortion. For the sake of interest, I’ve focused on methods that would be unusual today, and not on methods that are still regularly practiced—like abstinence, coitus interruptus, or fertility awareness—to similar effect now as a few centuries ago. These items are in no particular order.

Citric acid is said to have spermicidal properties, and women used to soak sponges in lemon juice before inserting them vaginally. Mentioned in the Talmud, this was a preferred method of birth control in ancient Jewish communities. The sponge itself would act as a pessary—a physical barrier between the sperm and the cervix. The great womanizer Casanova was said to have inserted the rind of half a lemon into his lovers as a primitive cervical cap or diaphragm, the residual lemon juice serving to annihilate the sperm. Lemon- and lime-juice douches following coitus were also recommended as a form of birth control, but this method was likely less effective, since sperm can enter the cervix—and hence out of reach of any douching—within minutes of ejaculation. Incidentally, some alternative medicine practitioners today suggest that megadoses of vitamin C (6 to 10 g a day) could induce an abortion in women under 4 weeks of pregnancy, but there’s no evidence that citrus fruits were used in this way in ancient times.

Queen Anne’s Lace is also known as wild carrot, and its seeds have long been used as a contraceptive—Hippocrates described this use over two millennia ago. The seeds block progesterone synthesis, disrupting implantation and are most effective as emergency contraception within eight hours of exposure to sperm—a sort of “morning after” form of birth control. Taking Queen Anne’s Lace led to no or mild side effects (like a bit of constipation), and women who stopped taking it could conceive and rear a healthy child. The only danger, it seemed, was confusing the plant with similar-looking but potentially deadly poison hemlock and water hemlock.

Pennyroyal is a plant in the mint genus and has a fragrance similar to that of spearmint. The ancient Greeks and Romans used it as a cooking herb and a flavoring ingredient in wine. They also drank pennyroyal tea to induce menstruation and abortion—1st-century physician Dioscorides records this use of pennyroyal in his massive five-volume encyclopedia on herbal medicine. Too much of the tea could be highly toxic, however, leading to multiple organ failure.

Blue cohosh, traditionally used for birth control by Native Americans, contains at least two abortifacient substances: one mimics oxytocin, a hormone produced during childbirth that stimulates the uterus to contract, and a substance unique to blue cohosh, caulosaponin, also results in uterine contractions. Midwives today may use blue cohosh in the last month of pregnancy to tone the uterus in preparation for labour. The completely unrelated but similarly named black cohosh also has estrogenic and abortifacient properties and was often combined with blue cohosh to terminate a pregnancy.

Dong quai, also known as Chinese angelica, has long been known for its powerful effects on a woman’s cycle. Women drank a tonic brewed with dong quai roots to help regulate irregular menstruation, alleviate menstrual cramps and help the body regenerate after menstruation. Taken during early pregnancy, however, dong quai had the effect of causing uterine contractions and inducing abortion. European and American species of angelica have similar properties but were not as widely used.

Rue, a blue-green herb with feathery leaves, is grown as an ornamental plant and is favored by gardeners for its hardiness. It is rather bitter but can be used in small amounts as a flavoring ingredient in cooking. Soranus, a gynecologist from 2nd-century Greece, described its use as a potent abortifacient, and women in Latin America have traditionally eaten rue in salads as a contraceptive and drunk rue tea as emergency contraception or to induce abortion. Ingested regularly, rue decreases blood flow to the endometrium, essentially making the lining of the uterus non-nutritive to a fertilized egg.

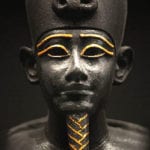

In the ancient medical manuscript the Ebers Papyrus (1550 BCE), women were advised to grind dates, acacia tree bark, and honey together into a paste, apply this mixture to seed wool, and insert the seed wool vaginally for use as a pessary. Granted, it was what was in the cotton rather than the cotton itself that promoted its effectiveness as birth control—acacia ferments into lactic acid, a well-known spermicide—but the seed wool did serve as a physical barrier between ejaculate and cervix. Interestingly, though, women during the times of American slavery would chew on the bark of cotton root to prevent pregnancy. Cotton root bark contains substances that interfere with the corpus luteum, which is the hole left in the ovary when ovulation occurs. The corpus luteum secretes progesterone to prepare the uterus for implantation of a fertilized egg. By impeding the corpus luteum’s actions, cotton root bark halts progesterone production, without which a pregnancy can’t continue.

In South Asia and Southeast Asia, unripe papaya was used to prevent or terminate pregnancy. Once papaya is ripe, though, it loses the phytochemicals that interfere with progesterone and thus its contraceptive and abortifacient properties. The seeds of the papaya could actually serve as an effective male contraceptive. Papaya seeds, taken daily, could cut a man’s sperm count to zero and was safe for long-term use. Best of all, the sterility was reversible: if the man stopped taking the seeds, his sperm count would return to normal.

Silphium was a member of the fennel family that grew on the shores of Cyrenaica (in present-day Libya). It was so important to the Cyrenean economy that it graced that ancient city’s coins. Silphium had a host of uses in cooking and in medicine, and Pliny the Elder recorded the herb’s use as a contraceptive. It was reportedly effective for contraception when taken once a month as a tincture. It could also be used as emergency birth control, either orally or vaginally, as an abortifacient. By the second century CE, the plant had gone extinct, likely because of over harvesting.

Civilizations the world over, from the ancient Assyrians and Egyptians to the Greeks, were fascinated by mercury and were convinced that it had medicinal value and special curative properties, using it to treat everything from skin rashes to syphilis. In ancient China, women were advised to drink hot mercury to prevent pregnancy. It was likely pretty effective at convincing a woman’s body that she wasn’t fit to carry a child, leading to miscarriage, so in that sense, it worked as a contraceptive. However, as we know today, mercury is enormously toxic, causing kidney and lung failure, as well as brain damage and death. At that point, pregnancy would probably be the least of your worries.