These premonitions are actually more common than you might think. And it’s not just doom-filled calendars and ancient textbooks from the middle ages; there are plenty of contemporary premonitions that have been published, funnily enough, in works of fiction. Most literary forecasts that pop up in books are often brushed off as purely coincidental or chalked up to being educated guesses, but some of them are almost too unsettling for words. So let’s take a look.

10 Super Sad True Love Story by Gary Shteyngart

The novel Super Sad True Love Story, published in 2010, follows the romantic entanglement of Lenny Abramov and Eunice Park in a near-future dystopian New York, where life is dominated by technology and bad debt. Credit rating is broadcasted to the world through “apparats,” which bear a striking resemblance to the iPhone 4. In the novel, economic chaos reigns. The U.S. is hopelessly in debt to China, the dollar is devalued, America has defaulted on its debt, and China scolds the country publicly. This exact event was mirrored in real life across international news channels when China stated that Washington must “cure its addiction to debt” less than a year later.[1] Shteyngart also managed to predict the Occupy Wall Street Movement in 2011. And though his predictions are parodic for sure, most of them have come true, proving, perhaps, that we live in a world where reality takes its cues from fiction.

9 2001: A Space Odyssey by Arthur C. Clarke

Although many consider 2001: A Space Odyssey a film and solely that, there was, in fact, a book that was written concurrently alongside the screenplay by Arthur C. Clarke, based on his short story, “The Sentinel.” It roughly follows a similar plotline but is based more on the revised version of the script and not the deviation the film eventually took. However, in both versions, we get a glimpse of the “newspad,” a device that features instant access to periodicals and other information all across the world. It looks like an iPad and works like one too. The book was published in 1968, and the iPad was introduced in 2010, 42 years after the film and movie came out, so it’s no wonder that Kubrick is regarded as the sci-fi seer of his time.[2] Then again, perhaps it wasn’t Kubrick who saw the future but Steve Jobs who copied Kubrick?

8 Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift

In the world-famous Gulliver’s Travels, Swift takes us on several fantastical adventures across the hidden corners of the globe, where Lemuel Gulliver meets the Lilliputians in a far-off country, encounters the giants in Brobdingnag, and then goes on to visit the flying land of Laputa, where Swift’s premonitions rapidly come into play. It turns out that Laputa’s astronomers had discovered that Mars has two moons, 150 years before Asaph Hall observed them in 1877. The fact that his prediction was based on mere conjecture is far more impressive than someone who makes an educated and informed guess, as even their proximity and orbit are fairly accurate.[3] Hall named the moons Phobos and Deimos. In a nod to Gulliver’s Travels, a crater on Deimos was named Swift after the writer himself, a tribute as remarkable as the premonition that inspired it.

7 Looking Backward: 2000–1887 by Edward Bellamy

Living in a time of social and economic turmoil in the late 19th century, Edward Bellamy grew embittered by the slow creation of labor unions, the violence surrounding the working-class majority, and hostility toward the privileged minority. Therefore, the American writer outlined his opinions and advice for the future in his novel Looking Backward: 2000–1887. In it, protagonist Julian West falls into a hypnotized deep sleep and wakes up a century later in 2000. The world has become a socialist utopia, where all of America’s goods are distributed equally to its citizens. It was Bellamy who first introduced the concept of credit cards to the world before they were ever invented when his character is taken to a store and given one that works like a debit card.[4] They acquire all the products and services necessary to lead a comfortable life, depending on the buyer’s situation. Although not exactly the same as the present day, it’s still with remarkable foresight that Bellamy created this concept—now adopted by banks all over the world. And to think that far ahead in the late 1880s was something only a very forward-thinking individual could conceive. That, or a time traveler.

6 Farhenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

Although a personal stereo didn’t appear until 1977, Ray Bradbury described earphones aimed at distracting one’s mind from the outer world in his dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451, published in 1953. The people in the Fahrenheit 451 society frequently use “seashells” and “thimble radios,” which bear a striking resemblance to the earbuds and Bluetooth headsets of our modern life. When the novel came out, headphones were large and cumbersome things. Nevertheless, Bradbury imagined these tinier headphones, which rested in the ear canal and played music to Montag’s sleeping wife. These “seashells” went from science fiction to science fact in 2001, when Apple designer Jonathan Ive debuted earbuds. When Ray Bradbury was asked whether he expected the future to be like the nasty one he described in Fahrenheit 451, he answered, “I don’t try to predict the future. All I want to do is prevent it.[5]

5 From the Earth to the Moon by Jules Verne

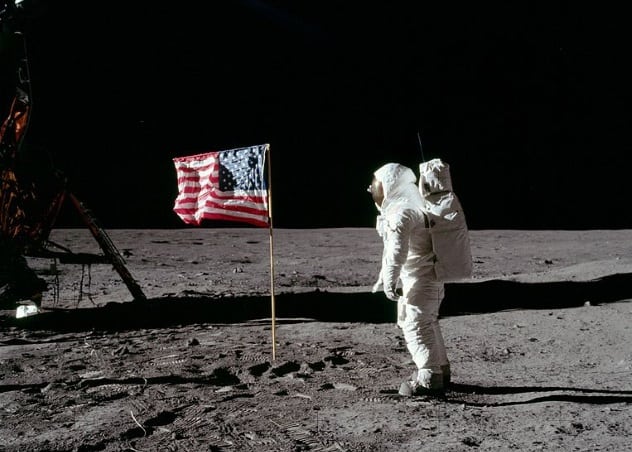

It’s not that out there for science fiction to feature on this list because the genre is, by default, so very ahead of its time—or any time for that matter. Futuristic cities, societies, technology, and transportation methods all form part of sci-fi’s integral allure. The forward-thinking individuals who come up with these tales can’t help occasionally visualize events that come true. But to predict something a whole century before it actually happened, and in 1865 no less, a time when plumbing wasn’t even a regular fixture in most residences? That’s a feat that can only be credited back to revolutionary author Jules Verne, the father of modern science fiction. In his book From the Earth to the Moon, Verne predicted the Moon landing, sparking interest in space travel across the world. Aside from the sheer improbability of such a prediction so early on in human technology, some parallels are simply disturbing. Verne’s main character believes he can shoot a cannon all the way to the Moon and, despite skepticism, raises enough funds to have the rocket built. Amazingly, the result looks a lot like the real-life Apollo capsule, even containing enough space to hold three people—just like the real one built over 100 years in the future. In the book, this launch cannon was named Columbiad by the main character, and as you’ll know, the real-life command module was later dubbed the Columbia—a probable nod to Verne’s literary work. Another of Verne’s astounding premonitions is that of location. As if dictating real life, Texas and Florida fight over who gets to launch the cannon, eventually settling on Florida as the launch site, while Texas gets the command center.[6]

4 Debt of Honor by Tom Clancy

When Condoleezza Rice, then the national security adviser for the Bush administration, claimed after rel=”noopener” target=”_blank”9/11 that no one could have predicted an attack involving aircraft, it was very much a proverbial foot-in-the-mouth scenario because long before the 9/11 attacks happened, Tom Clancy predicted a similar act of terrorism in his 1994 thriller novel Debt of Honor. In it, a terrorist hijacks a jetliner and crashes it into Washington’s Capitol Building to take out the whole government and an entire chain of command. This is, of course, reminiscent of the actual September 11th attacks, only in the book, the events lead up to radical governmental change. The book might seem uncannily prophetic, though not many people seemed eager to point out the similarities, and even Clancy himself was quick to dismiss the claims of his being a modern seer. Predictive power or not, Clancy said the similarities arose as a result of his ability to observe facts from his research and understand human nature.[7] Right.

3 The Plot Against America by Philip Roth

The late Philip Roth’s 2004 masterpiece The Plot Against America doesn’t stand out just because of its literary prowess, although that would be a solid enough reason in itself. Instead, what makes this novel remarkable are the startling similarities between the protagonist’s presidential campaign and Donald Trump’s actual election, which took place 12 years after the book was published. In his alternate universe, Roth reveals how a demagogic celebrity could launch a presidential campaign—perceived as a joke by the other party—and still win.[8] Although he wasn’t called Trump, Charles Lindbergh (also a real person), an aviator stunt sensation, beat Roosevelt in the 1940 election by gaining the votes of thousands of Republicans and right-wing supporters. Like Trump’s own campaign, which was sustained by promoting the inadequacy of the other party and not through advocacy of his intended objectives, Lindbergh’s appalling campaign wins by a landslide, and it’s considered the “end” of democracy. This was believed to be an impossible feat, as both Lindbergh and Trump went up against people who were better-funded, qualified, and educated; this puts in question the very nature of politics. Both the fictional and real-life presidents’ morals are twisted: Lindbergh supports Hitler’s doctrine of thinking and openly blames the Jewish community on their “natural” propensity for war and disaster, something that mirrors Trump’s scapegoating of Muslims and Mexicans. Whatever the case may be about Roth and his foreshadowing a future presidency, there are definite echoes of Lindbergh in Trump’s fearmongering speeches on foreign threats.

2 The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket by Edgar Allen Poe

The story of Richard Parker is next up on our list. There was a time when Edgar Allen Poe wasn’t half as well-known as he is today, a time when his name didn’t inspire horror or illicit awe in those who came across his (back then nonexistent) stories. In essence, it didn’t generate much of anything to anyone except those privileged few who were acquainted with him. Yet his first (and only) full-length novel was published in 1838, elevating his status from unknown writer to unknown author (not that this title stuck, as you very well know). The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket was an odd tale, unlike Poe’s more famous short stories, as it didn’t feature any ghosts, vengeful or otherwise, and not one single raven. Instead, the plot followed the maritime misadventures of Arthur Pym, who went from mutineer to murderer in a few short (illicit) boat trips across the Atlantic. No story that involves cannibalism is going to have a happy ending, so it should come as no surprise that the Grampus floods and leaves its crew lost at sea without food or water. Desperate, the crew members draw lots to identify the poor sucker who will sacrifice himself—and his flesh—to the starving crew. But, unfortunately, it was 17-year-old Richard Parker, one of the ship’s mutineers, who lost. Forty-six years later, Britain’s last trial for cannibalism at sea caused a stir in English courts, the details of the morbid events inspiring horror in all those who heard it.[9] Edgar Allen Poe’s story came alive when the Mignonette, a small yacht which had set sail to Australia from England, sank at sea, leaving the four-man crew to fight for their lives aboard a small wooden dinghy. Weakened and on the brink of death, the captain and mate killed a young lad who’d caved and overdosed on saltwater, using him as sustenance to survive. The unfortunate lad’s name? Richard Parker. Two days later, the straggling survivors were rescued by a passing German ship. Twisted irony? Check. Perverse coincidence? Check. If Poe was indeed gifted with a touch of clairvoyance, it was never openly or publicly spoken about. In fact, after his short stories started gaining momentum in literary circles, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket faded into obscurity. Perhaps reality is a little harder to take than fictional ravens…

1 The Wreck of the Titan: Or, Futility by Morgan Robertson

The sinking of the Titanic is undeniably one of the most written-about events in human history. And that’s not even taking into account the scores of news features, documentaries, films, and, of course, chart-topping ballads that were inspired by the passenger liner’s tragic demise. There is one particular Titanic tale, however, that stands out. That’s because it was written before the Titanic sank. That’s right! A mere 14 years before the famous ship struck an iceberg one chilly night in April 1912, Morgan Robertson sat down and penned a story so unnervingly similar to its real-life counterpart that one can’t help but wonder if he was, in fact, a clairvoyant, rather than a writer with an overactive imagination.[10] In 1898, The Wreck of the Titan: Or, Futility hit bookstores across the United States and Europe, regaling readers with a chilling story of a terrible maritime disaster, of which there were only a few survivors. Morgensen tells the story of John Rowland, a down-on-his-luck deckhand working aboard the Titan, the largest cruise ship ever built, a ship that was declared unsinkable by experts and the public. Ring any bells yet? The boat’s name itself should be enough to make you do a double-take, but there’s more. In the book, the Titan was described as a modern marvel—the largest ship ever built, ahead of its time, even. When it comes to the boat’s physical features, that’s where things get really odd. Where the Titan was measured at 244 meters (800 ft) long, the Titanic was only 25 meters (82 ft) longer. Where the Titanic carried 20 lifeboats, the Titan carried 24. These are physical resemblances so striking it’s almost as if the White Star Line used Robertson’s creation as a blueprint for the Titanic’s design. Yet the resemblances don’t end there. Both the Titan and the Titanic struck an iceberg on the starboard side of the deck in the North Atlantic. In April. Robertson denied the ability to predict the future, attributing the coincidence instead to his being an experienced seaman. Although this could account for the Titan’s similar size and an insufficient number of lifeboats, the fact that the Titan was struck in practically the same spot in the North Atlantic—in the same month—is still one hell of a coincidence. Elena Alston is a content writer based in London. Both her fiction and nonfiction has featured in IMIS, the Drabble, the Daily News Service, and the Prisma.