10The Awesome New Cannon (That Accidentally Killed The Secretary Of State)

While it still had sails, the USS Princeton was the first steam warship with a screw propeller in the United States Navy (earlier steam-powered vessels had been pushed along by a paddlewheel). Like any new technology, the Princeton had a few kinks to work out. In this case, the kinks were devastatingly fatal. On February 28, 1844, President John Tyler decided to show the new ship off. He and 400 other dignitaries boarded the Princeton for a cruise down the Potomac. Also on board was an extremely large new cannon nicknamed “the Peacemaker.” The captain of the Princeton, Robert Stockton, was eager to demonstrate the weapon, against the wishes of artillery designer John Ericsson. The first shot went well, garnering the applause of the audience, as did the second. The third shot—well, that caused one of the worst naval peacetime disasters in history. The gun exploded, killing six people: Secretary of State Abel Upshur; Secretary of the Navy Thomas Gilmer; Beverly Kennon, the Navy’s Chief of Construction; Virgil Maxcy, the American diplomat to Belgium; President Tyler’s slave, Armistead; and David Gardner, the father of Julia Gardner, the woman Tyler had just proposed to. There’s a good chance Tyler himself would have been killed (or at least severely injured) had he not been drinking below deck during the first two shots. He was on his way back up when the third shot was fired. Just in case you were wondering, Julia Gardner did end up marrying President Tyler.

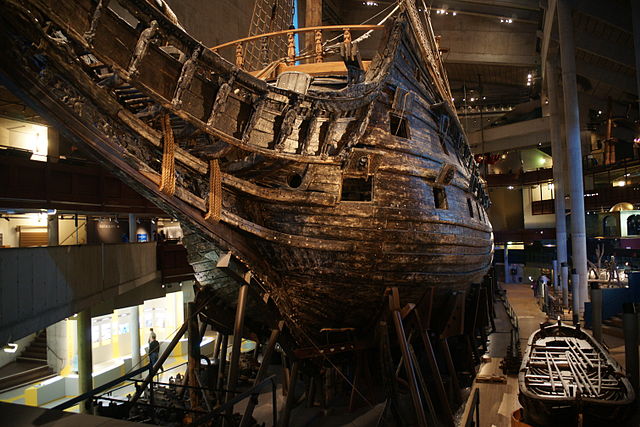

9The Embarrassing Single Voyage Of Sweden’s Greatest Ship

In 1628, Sweden was at war with Poland. Desperate for an advantage, King Gustav II Adolph of Sweden had commissioned the construction of an extremely powerful ship—the Vasa. Intended to be the pride of the Swedish fleet, no expense was spared in her construction. Unfortunately, Gustav II Adolph proved to be less than competent in the ways of shipbuilding. He changed the design and armament orders so frequently that the ship became a hodgepodge of often-contradictory ideas. To add to the mess, the builders of the time did not fully understand how to test for ship stability. On August 10, 1628, the Vasa grandly set sail on its maiden voyage from Stockholm, cheered by a crowd of patriotic onlookers. After a few minutes, a small gust of wind knocked the ship over and it sank. Unfortunately, the consequences were anything but comical. Around 150 people were on board the ship, including women and children, and around 30 of them died. Additionally, the construction costs, which were astronomical, were a total loss. The ship’s captain survived—only to be unceremoniously thrown in jail. He and his crew were suspected of incompetence, but an inquiry revealed they were innocent. Ultimately, no one was blamed for the disaster, but the Vasa had been an embarrassing and expensive failure. It wasn’t raised until 1961.

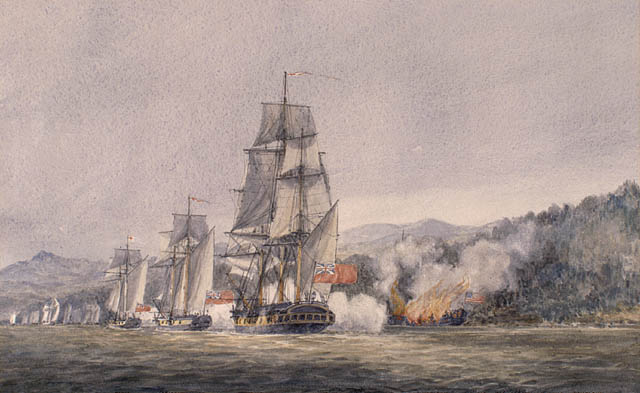

8When Benedict Arnold Took On The British Navy With Barges

Benedict Arnold’s name is synonymous with betrayal, but before becoming an infamous turncoat, Arnold was actually one of America’s best generals. Case in point: the Battle of Valcour Island. In 1776, in the midst of the Revolutionary War, the British were planning a naval invasion of the colonies via the Hudson River from Canada. A successful invasion would have been absolutely disastrous for the rebels. To counter it, they set to work building a ragtag navy. Benedict Arnold had plenty of pre-war naval experience, so he was placed in charge of construction, which wasn’t exactly a walk in the park. Shipbuilders weren’t plentiful in upstate New York and experienced sailors were almost as hard to come by. But by October, Arnold had managed to assemble a fleet of 16 ships. Sixteen isn’t a bad number considering Arnold’s time and monetary constraints. But half the fleet were actually small, flat-bottomed river barges known as gundalows, with guns slapped on wherever they would fit. They were powered by a mixture of sails and oars. Imagine going up against the most powerful navy in the world in a boat you have to row. The British fleet was nearly twice as large. In October 1776, the two navies clashed near Valcour Island in Lake Champlain. Unsurprisingly, the American fleet was defeated soundly, losing 11 of its ships. But tactically, Arnold’s bold stand was a victory for the Americans—the battle forced the British to delay their invasion until 1777. By that time, the Continental Army was large enough to actually put up a fight.

7When Holland Became An Island

The Netherlands could be considered the forgotten superpower of the Age of Sail. Their naval prowess was comparable to Britain, and at one point the small European nation even owned a sizable chunk of North America (creatively called New Netherland), which extended through parts of modern-day New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Maryland, and Delaware. Back in the 17th century, the Netherlands consisted of several provinces, most of which formed the Dutch Republic. However, a minority of provinces were actually held by Spain, an area which correlates to modern-day Belgium and Luxembourg. France wanted the Spanish Netherlands. The problem? The Dutch Republic wasn’t okay with that. Thus began the Franco-Dutch War, which lasted from 1672–1678. At the time, the Dutch Republic was led by William III of Orange. You might be familiar with him from British history—he was such an effective leader that the British asked him to come and rule them in 1689. To combat the threat of invasion, William actually opened the dikes and flooded a huge area around the city of Amsterdam. Known as the Dutch Water Line, this essentially turned the province of Holland into an island. The idea had been conceived and prepared a few decades earlier by Maurice of Nassau and his brother Frederick Henry. The Water Line instantly made the Netherlands almost impossible to invade, as William was able to use the formidable Dutch navy to fend off attacks from the French, and even the British and Swedish, who had joined the French cause. With money running low and Great Britain and Spain threatening to join the Dutch, France was forced to give up. Several decades after the war was over, France did gain control of the Spanish Netherlands through the ascension of a French duke to the Spanish throne. It only lasted for six years.

6The Anarchist Pirate Who (Possibly) Founded A Micronation

Captain Misson, a Frenchman, was no ordinary pirate. He felt that piracy offered a chance to improve the lives of the common people and reject the monarchial establishment. In many ways, Misson embodied the ideals of the French Revolution a century before it happened. Misson’s family was not especially poor, but it was far too large to support all of its members. Misson, who was well educated, decided to volunteer for the French navy. In the late 17th century, he boarded the frigate Victoire, which left for the Mediterranean. There, Misson met his greatest companion, a disgruntled priest named Caraccioli, who joined the crew. Together, Misson and Caraccioli beat back Moors and fought the British. During one major battle with the British, the captain of the Victoire was killed. Caraccioli immediately saluted Misson as the new captain—forcing him to confront a difficult decision. He could return to France and accept a small commission, or he could lead the crew as a free citizen of the world. Misson never reported to France again. With a crew of around 200, the Victoire sailed for Madagascar. After some conflict with the natives, Misson established the island as a pirate haven, a tradition that was to continue throughout the Age of Sail. Misson even created a territory on the island known as Libertatia, which was effectively a sovereign state. The details of Misson’s life were extensively documented by Daniel Defoe, who also wrote Robinson Crusoe. If Misson’s story sounds too crazy to be true, that’s because it might well be. While the account of his life is presented as real, many historians have accused Defoe of making the whole thing up.

5Spain And Britain Trade Armadas

In the 16th century, Spain rose to become the most powerful nation in the world, dominating the seas and conquering the New World. Perturbed by England’s stubbornly Protestant Queen Elizabeth, Spain’s Catholic monarch, Philip II, thought it would be no trouble to invade and conquer the northern backwater. In 1588, Philip dispatched the Invincible Armada, one of the most intimidating naval forces ever assembled, consisting of around 130 ships. But the size of their fleet did little to help the Spanish. They lacked organization, and the British defense consisted of small, fast ships that could fire at the Armada from afar. The fleets met at the Battle of Gravelines on August 7, but both were left relatively unscathed. Not long after the battle, a huge storm more or less destroyed the Armada. The importance of this battle should not be downplayed. It gave the English a massive confidence boost and opened the door to Britain’s eventual naval dominance. But the defeat wasn’t the end of Spanish power. In fact, with money flowing from the New World, Spain’s coffers were quickly refilled, and they were ready for another fight—as were the British. Cue the British Counter Armada of 1589, led by Sir Francis Drake. The fleet sailed down to the Iberian Peninsula, where it was handily defeated. Then there’s the Spanish Armada of 1596, which headed for Ireland until it was destroyed by a storm. Spanish Armada of 1597? Storms again. Plans for yet another Armada ended prematurely with Philip’s death. England and Spain finally signed a peace agreement in 1604.

4How The Confederates Used A Sunken Federal Ship To Change Naval Warfare

The Battle of Hampton Roads sounds like something from steampunk fan fiction. In April 1861, during the American Civil War, Northern troops were forced to evacuate the Norfolk Navy Yard in Virginia due to advancing Confederate forces. Not everything could be salvaged, and rather than let the Confederates capture it, Union troops sunk the frigate USS Merrimack. The Confederates captured it anyway, raising it from its watery grave. Desperate for some kind of naval advantage, the rebels decided to transform the salvaged frigate into something else entirely—something much more powerful. The USS Merrimack became the CSS Virginia, one of the world’s first steam-powered ironclad warships. That might not sound like a big deal, but in an era of wooden ships, the Virginia was a huge metal monster, like a cross between a submarine and a trireme (sans the sails). Its guns were incredibly powerful and its ram was absolutely lethal. It essentially outclassed every other ship in the world. In March 1862, the Confederates decided to use the Virginia, along with a few other ships, to try to end a Union naval blockade. The Virginia steamed out of Norfolk and went straight after the USS Cumberland. One blow from its ram destroyed the Cumberland, but the ram became stuck and the crew was forced to detach it before the Virginia was pulled under by the sinking enemy ship. The Virginia then bombarded the USS Congress, destroying it. After only two hours, the Virginia was plowing through the Union’s forces—the enemy’s fire simply couldn’t penetrate its metal plating. But here’s the surprise twist: By the next day, an unexpected challenger had arrived to take on the Virginia. It was the USS Monitor, a strange raft-like metal behemoth designed by John Ericsson—the world’s first iron-hulled steamship. When the Virginia tried to attack the USS Minnesota, it found itself suddenly in combat with the Monitor. The Virginia had dispatched two ships in two hours the previous day, but the struggle against the Monitor lasted much longer. Each ship’s armor was just too strong, with cannon fire bouncing off. They fought to a brutal draw, and the Union blockade held. Fittingly, the Virginia was eventually destroyed by the Confederates themselves, in order to keep the ironclad from falling back into Union hands.

3The Scottish-American Sailor Who Successfully Invaded Britain

If you assumed that the US didn’t have much of a navy during the American Revolution, you’d be right. But they did a lot with a little. One of the Revolution’s major naval heroes was a Scottish pirate named John Paul Jones. Jones was fond of harassing British ships, but he didn’t stop there—on April 23, 1778, Jones successfully invaded England. It was the only engagement of the war fought on English soil, and the last successful invasion of England. However, there’s a reason you probably haven’t heard of the attack—it was much more amusing than decisive. Under the cover of darkness, Jones invaded the town of Whitehaven with a handful of men. Their intention was to burn the town down, but one of his men inexplicably warned the British of the fires Jones had started (and the impending property damage). Jones and company fled, causing only a few hundred pounds worth of damage. Jones then sailed to Kirkcudbright Bay, Scotland. While there, he hatched a plot to kidnap and ransom the Earl of Selkirk. The Earl wasn’t there when Jones arrived, so he stole all of the silverware and fine china instead, including a teapot that had just been used by the Earl’s wife. There was still tea in it. Due to his illustrious naval career, Jones was showered with honors by the US and France. However, while subsequently serving in the Russian navy, Jones was plagued with lack of recognition and dogged by false accusations. He died soon after returning to Paris in 1790.

2Commodore Abraham Whipple Captured A Fleet Without Firing A Single Shot

Commodore Abraham Whipple stands right alongside John Paul Jones as a hero of America’s fledgling navy. During the revolution, Whipple demonstrated a knack for innovative and intuitive tactics—a must for such a weak navy. Whipple is best known for his association with the Gaspee Affair of 1772. A much-hated British schooner, the Gaspee, was responsible for enforcing British customs regulations around Rhode Island. When the Gaspee ran aground in pursuit of another ship, Whipple led a group of men in rowboats to torch and pillage the schooner. The affair was a major incident in the build-up to the American Revolution, but Whipple avoided identification or arrest. Whipple would engage in another covert operation in 1779, this time commanding a fleet of ships and sailors instead of rowboats and angry townsfolk. Leaving from Boston, Whipple encountered a large British fleet off the coast of Newfoundland. The fleet was transporting an enormously valuable cargo—so Whipple concocted a plan to steal some of it. Under the cover of nightfall, Whipple led his ships toward the fleet. Instead of attacking, Whipple’s flotilla masqueraded as British ships, and led 10 or 11 of the enemy astray. By the morning, the lost ships were far too far to receive any help from the main fleet—and thus the largest loot of the war was Whipple’s for the taking.

1An Outnumbered British Fleet Defeated A Larger Force Without Losing A Single Ship

If there’s one figure who really stands out in the Age of Sail, it’s Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson. He routinely defied orders and attempted ill-advised naval maneuvers. Yet his endeavors (usually) turned out far better than any reasonable person could have predicted. Nelson was just the man to stop Napoleon from invading Britain. Napoleon knew that if could successfully land his troops, he would surely conquer Britain. The only thing standing between him and victory was the Royal Navy, which was by then the best in the world. At various times, Napoleon contemplated using balloons, or even digging a tunnel under the English Channel—but as we know, the invasion never occurred. In 1805, Napoleon assembled a combined Spanish and French fleet of 33 ships, led by Admiral Pierre de Villeneuve. The British moved quickly, and Nelson caught Villeneuve at Cape Trafalgar, off the coast of southern Spain, on October 21, 1805. The Battle of Trafalgar would become the most important naval battle of the Napoleonic Wars. The British fleet of 27 ships sailed directly towards Villeneuve’s fleet in two lines, contrary to all accepted naval tactics, and a bloody conflict ensued. Casualties were in the thousands on both sides, but Nelson’s bold gambit paid off spectacularly—while the majority of Villeneuve’s fleet was sunk or captured, the British didn’t lose a single ship. By Trafalgar, Nelson was already missing an arm and was blind in one eye. Thanks to an enemy sniper, he barely lived to the end of the battle which would be his greatest success. It’s said that upon hearing the cheering of the victorious British, he closed his eyes and died. Drew Patrick contributed to the research of this list. He is currently minoring in History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Joshua Garcia has also written for Knowledgenuts.