10 ‘Margaret Thatcher Invented Soft-Serve Ice Cream’

When Margaret Thatcher died in 2013, the bishop of London reignited the debate over whether or not one of Britain’s coldest leaders was involved in the unlikely invention of one of the world’s coldest treats—soft-serve ice cream. The story went massively mainstream, with news networks across the globe repeating the tale that Thatcher, who had a degree in chemistry from Oxford University, had briefly worked at J. Lyons & Company as a chemist. There, she reportedly helped to develop the method for adding extra air into ice cream to create a bizarre legacy. However, the story isn’t true at all. Soft-serve ice cream first came from the US, not Britain, and it seems to have been the brainchild of either Tom Carvel or J.F. McCullough. They stumbled on the idea independently and in different ways, but at around the same time—in the 1930s, well before Thatcher’s 1947 college graduation. Soft-serve as we know it today really took its shape in the 1960s, though, with the development of air pumps and other equipment. Tracking the source of this oft-repeated misconception is a little tricky, but the likely source is a strange one: Some of the earliest references to her involvement in ice cream technology come from members of the British left, who used it as a metaphor for her political career.

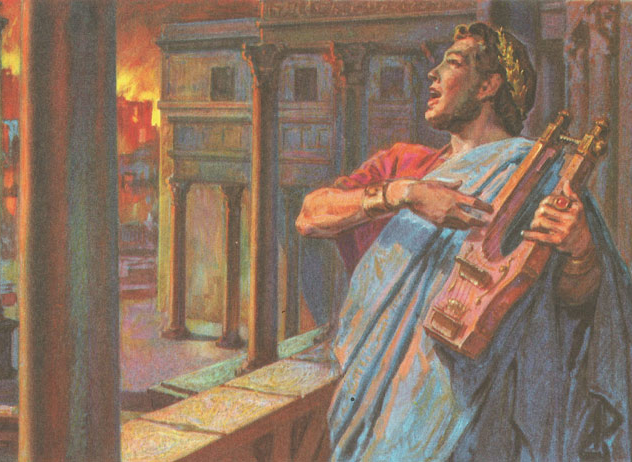

9 ‘Nero Fiddled While Rome Burned’

The story of a mad emperor fiddling away while his city burns is one of the most graphic snapshots we have of the ancient world and into the mind of one of history’s most infamous rulers. It is said that when fire ravaged Rome in AD 64, the hated emperor Nero happily fiddled the night away and ignored the disaster that was destroying his people. It seems legit enough, even if we don’t interpret “fiddling” as using an actual instrument and instead look at it in the other sense of the word. If you’re “fiddling around,” you aren’t really doing anything productive. Historians are certain that nothing is farther from the truth. Nero was not in Rome when the fire started; he was in his residence in Antium, about 56 kilometers (35 mi) away. And he actually did quite a bit to help the city as it was burning and during the aftermath, organizing relief efforts and even allowing those who had been forced from their homes to stay in his own royal residences and gardens. He ordered food sellers to cut their prices, distributed huge amounts of food himself, and paid for most of the relief efforts personally. So why do we continue to think the exact opposite of him? The rumor of Nero’s fiddling is an old one, dating back to the time of the fire. According to the historian Tacitus, crowds of people, now homeless and terrified, started the rumor that while the city burned Nero, well-known for his love of the arts, took to his own private stage to sing a song about Troy and its destruction. The story was picked up by later historians, and it seemed to ring true enough. People knew Nero was nuts, after all, so it made sense, particularly in light of his actions in the months after, when he built a new palace on the land that had been cleared by the fire—which he was also rumored to have started in the first place. While the image of the uncaring, mad emperor seems to fit with what we know about Nero, that leads us into another major misconception about him: Reading through accounts of the second-century writer Suetonius reveals a very different Nero, one known as being generous and merciful. He did indeed have a huge love for the arts, endearing him to at least a part of the population and suggesting that during his rule, he was not quite the universally hated nut-job he has the reputation of being today.

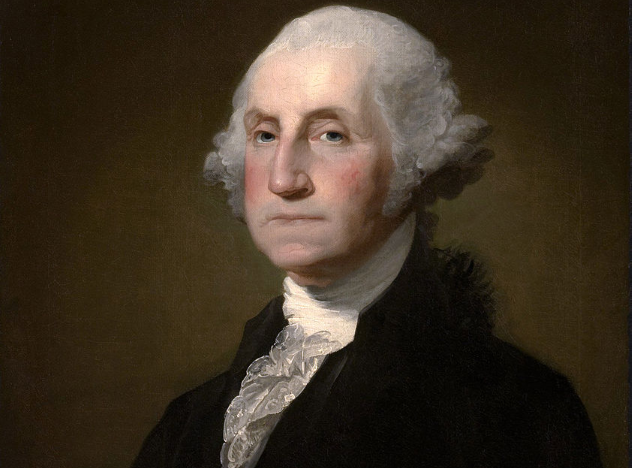

8 ‘George Washington Had Wooden Teeth’

The story that George Washington had wooden dentures is one that still shows up in the occasional history textbook, and even though a good number of people know that this is a widespread misconception, fewer know the story of how Washington’s teeth played a role in the American Revolution—and why we think they were wooden in the first place. First, the misconception: Washington did wear dentures and was plagued with constant pain from them, and it shows in the official portraits of him. His dentures are the reason he looks slightly different in various paintings, and the dentures wore were made of a number of different materials, including ivory, lead, and gold. The wooden teeth story likely originated from the stained, grainy appearance that his teeth gradually acquired, and it was kept as a way to make Washington more accessible as an “everyman” sort of character. One part of the myth, the idea that Washington carved his own dentures, is at least partially true, as we do know that he did repair his own teeth. Washington was always rather secretive about the constant troubles with his teeth, and in 1781, British troops intercepted a letter from Washington to his dentist. In it, Washington requested that cleaning supplies be sent to him outside of New York, as he wasn’t planning on being in Philadelphia any time soon. The British interpreted this as valuable military intelligence and assumed that the personal communication meant that all the information in the batch of mail was the real thing. Based on that, Sir Henry Clinton decided against reinforcing their troops at Yorktown, an oversight that led to the defeat of Lord Cornwallis and his men. While Washington’s teeth might not have been wood, we do know that he saved several of his own teeth at Mount Vernon and that he once spent 122 shillings on nine human teeth destined for inclusion in future sets of dentures.

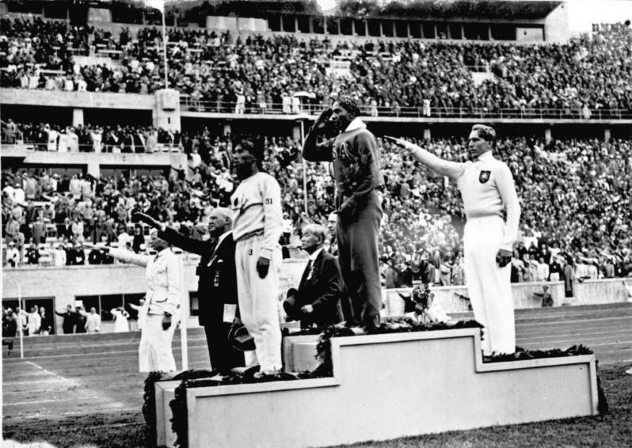

7 ‘Hitler Snubbed Jesse Owens’

In 1936, Nazi Germany hosted the Olympics, in which US athlete Jesse Owens became the first person to claim four gold medals in a single edition of the games. The famous story is that Hitler, renowned for his racism, snubbed Owens after his incredible victories. The real story is much stranger—and much less to America’s liking. When Owens returned to the States, he had nothing but good things to say about his time in Nazi Germany. Not only did he befriend another athlete named Lutz Long (who Owens would never see again, as Long was killed in World War II), but he had nice things to say about Hitler, too. Owens was quoted by the press as saying, “Hitler had a certain time to come to the stadium and a certain time to leave. It happened he had to leave before the victory ceremony after the 100 meters. But before he left, I was on my way to a broadcast and passed near his box. He waved to me and I waved back.” Throughout the interviews, Owens remained focused on the games rather than the politics, saying that it would have been poor sportsmanship to say anything negative about his host country. Hitler’s comments on race and the competition were supposedly voiced only to Albert Speer, not to the athletes themselves. There was, however, one world leader who did snub Owens—Franklin Delano Roosevelt. When Roosevelt invited all the winning Olympians to the White House, Owens was the only one not to receive an invitation. He never got a congratulatory telegram or letter, either, and Owens later said, “Hitler didn’t snub me; it was our president who snubbed me.”

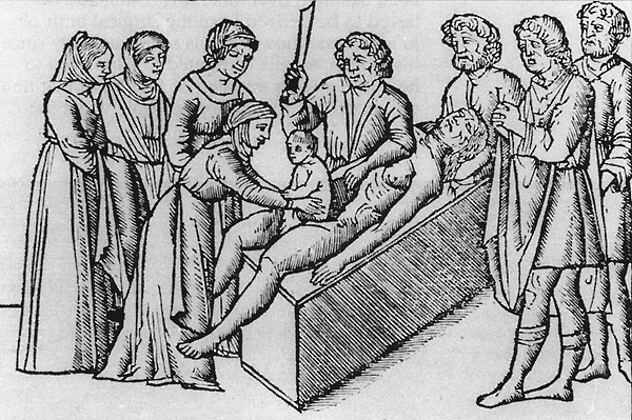

6 ‘The Cesarean Section Was Named For Julius Caesar’

The story goes that Julius Caesar gave his name to the cesarean section, the method by which he was supposedly born. This myth has been incredibly long-lived, and woodcuts from the 16th century even show the scene that supposedly gave the name to the procedure. We know that this long-lived and often-told misconception is just that for a couple of reasons, one of the foremost being that Caesar’s mother was said to have been alive at least long enough to see her son invade Britain. The story, however, says that the future ruler was removed from her body after she had died, which was actually common practice in the early days of cesarean sections. The idea that they were only performed in the most dire of circumstances is implied in the more likely source for the term—the Latin word caedare. It means simply “to cut,” and it was written into Roman law that a pregnant woman who had recently died or was dying would be required to undergo the then-drastic measures to cut the baby free in order to try to save it. There are no records of a woman surviving the procedure until 1500, and even then, it wasn’t performed by a physician or surgeon. It was done by Jacob Nufer, whose medical work experience involved castrating pigs. That story is debated, too, but we do know that it was about this time that views on cesareans were changing, along with the name. A book on midwifery from 1598 was the first to call it a “cesarean section,” and the focus shifted to saving both mother and baby.

5 ‘Queen Victoria And Prince Albert Lived In Domestic Bliss’

The marriage of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert has long been touted as one of history’s great love stories, ending when his death plunged her into mourning for the rest of her days. It was only fairly recently that investigation into the personal diaries and letters of various members of the Victorian court found that lurking behind the carefully crafted misconception and misrepresentation was something entirely different. A BBC documentary looked at the letters and what really went on behind the public face that the royals presented to the world found a mother who hated her dribbling babies and who was terrified that her role as a breeding “rabbit” would allow her husband to leech away her power and control, over both royal affairs and her entire family. For Albert’s part, he wrote of his worries that Victoria had inherited the madness that had crippled King George III, and at times, their arguments were so fierce that the the only way he could communicate with her was to pass notes under her door. They both considered their eldest son Bertie, the future Edward VII, a half-wit. After Albert fell ill—and ultimately died—after visiting his son and walking in the rain with him, Bertie became the target of Victoria’s wrath. For the 40 years after Albert’s death, Victoria exerted a shocking amount of control over the lives of her children and their spouses. Major events were scheduled around the menstrual cycle of Bertie’s wife, Princess Alexandra. Daily letters plagued Victoria’s oldest daughter Vicky, even though she was living in Germany. Leopold spent most of his life being told he was “common-looking” and an invalid, wrapped in wool and bullied by the servants assigned to him. Eventually, the future king severed all relations with his mother and succeeded her when he was 59 years old.

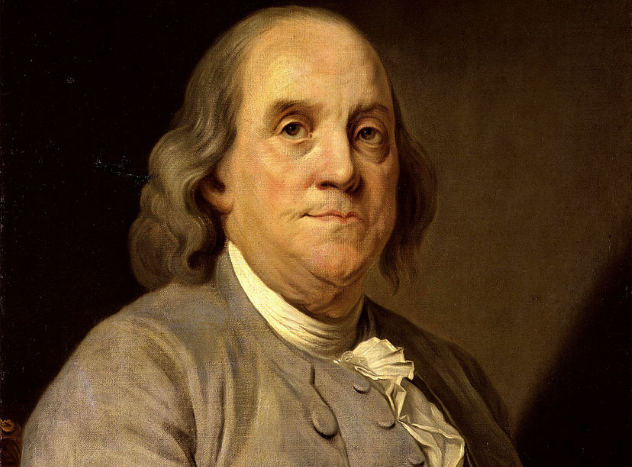

4 ‘Benjamin Franklin Wanted A Turkey To Represent the US’

Everyone recognizes the bald eagle as the symbol of the United States, but it’s been repeated countless times that Benjamin Franklin campaigned for another bird—the turkey. As fun as it is to imagine the US being symbolized by a turkey, the story absolutely isn’t true. What Franklin did do was write a letter to his daughter, in which he questioned the idea of the eagle as representative of the new American way of life. He called the eagle “a Bird of bad moral Character” and said that the bird is like “men who live by sharping & robbing he is generally poor and often very lousy.” He went on to comment that the design picked for the seal more accurately resembled a turkey than an eagle and mused that the turkey was a much nobler bird. Those thoughts were never made public, but Franklin did submit a design for the young country’s Great Seal. There were no turkeys involved, however. Instead, Franklin proposed using a scene from Exodus that depicted Moses confronting the pharaoh and resisting tyranny, just as the colonies had done. Franklin’s design was, of course, rejected, but Thomas Jefferson took Franklin’s proposed motto of “Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God” and used it for his own personal seal. The misconception about Franklin’s proposed design was only truly cemented in public consciousness in 1962, when The New Yorker released an edition with the Great Seal reenvisioned with a turkey as their cover art.

3 ‘King George III Was Mad’

George III is known as the Mad King for a good reason: Everyone agrees that there was something very, very bizarre about his behavior. After he turned 50, he was prone to attacks which left him suffering from hallucinations, disorientation, mania, and such drastic personality swings that the monarch, who had often been relied on to be a peacekeeping mediator, would assault staff and doctors alike. When he was lucid, he would talk about his illness, and in 1788, he appealed to his son and hoped that death would take him before another bout of madness. Some form of mental illness has always been the go-to explanation for the king’s behavior, and at the time, the treatment administered likely made his mental state even worse. Subjected to bleeding, purging, and sedation as well as being locked in a freezing room during the long winter months in an attempt to drive the illness from him, George III continued down his steep decline. After his son took the throne, his anguish and agony lasted for years, and his ultimate death was seen as a relief. Today, it’s theorized that he wasn’t suffering from a mental illness at all but from a genetic condition called porphyria. The disease, which also causes the physical ailments from which the king suffered (like severe abdominal pain), seemed to explain his problems. But the question remained as to why he only developed his symptoms during middle age if it was due to a genetic disorder. When pieces of the king’s hair were analyzed, they were found to contain levels of arsenic and lead that were almost unheard-of. While about 90 percent of people who carry the gene for porphyria never develop the condition, the presence of arsenic in the body can trigger the gene into action. When the king suffered from early abdominal pains that left him incapacitated, he was medicated with emetic tartar. This so-called medicine contained high amounts of arsenic, and the “madder” the king got, the more medicine they gave him, until he was reduced to a haunted shell of a man.

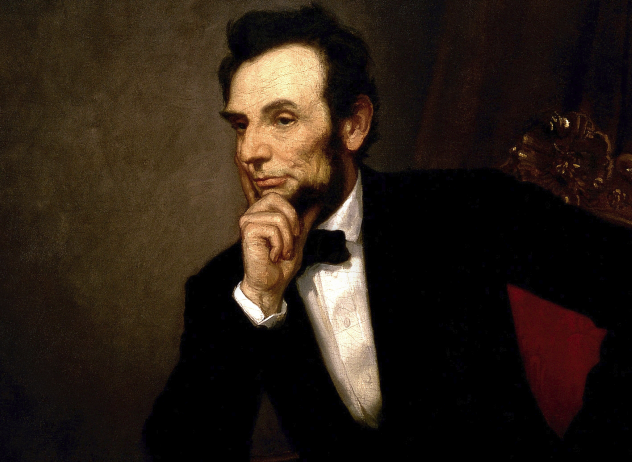

2 ‘Abraham Lincoln Penned The Gettysburg Address On A Train’

This is another myth that still shows up in history textbooks as fact: Lincoln was on his way to a dedication in Gettysburg and hurriedly penned the Gettysburg Address on a few scraps of paper and on the back of an envelope while he was on the train to the ceremony. In truth, Lincoln never wrote anything while he was on the train to Gettysburg; the earliest drafts of the speech were written while he was still in Washington, DC. The historic speech was revised on Lincoln’s first night in Gettysburg and again after his tour of the battlefield. The first mention in the idea that Lincoln’s most famous speech was a hastily penned piece showed up around two decades after the fact. The secretary of the interior under Lincoln, John P. Usher, added the story to what had already been written about Lincoln’s trip from DC to Gettysburg, and since Usher had been on the train with him, no one saw any reason to suspect that he was lying. After Mary Shipman Andrews wrote a short story in 1906 that was based around the idea, it was firmly cemented into history. At the time that the idea was shifting into the mainstream, there were two people who tried to stop Usher’s exaggeration from spreading. David Willis, who hosted the president while he was in Gettysburg, wanted to perpetuate another myth—that Lincoln had written the speech in its entirety while staying at Wills’s house. Lincoln’s personal secretary, John Nicolay, also voiced his opposition to the spread of the story. Nicolay had seen the early draft of the speech that Lincoln had written while he was still in Washington, and he (along with fellow secretary John Hay) had been presented with a handwritten copy of it. Both are in the Library of Congress.

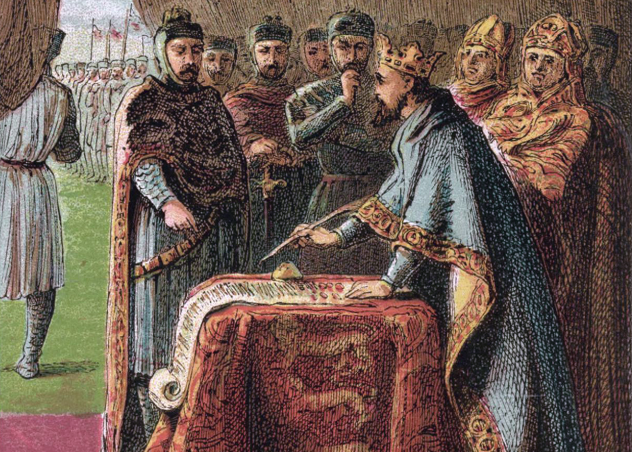

1 ‘King John Signed The Magna Carta’

This one might be a technicality, but it’s a technicality that even the Royal Mint has been called out for misrepresenting. We know that British history changed forever with the rule of King John and the adoption of the Magna Carta. In 1215, the world had finally had enough of the monarch’s insane cruelty, and John was forced to negotiate away much of the monarchy’s power with a document that held the king to a series of 63 laws and a council of 25 barons. He agreed, and even though he later appealed to the pope on the grounds that he had been unfairly forced to accept the terms of the deal, the ratification stood. On the 800th anniversary of the momentous event, the Royal Mint released a commemorative coin showing John holding the rolled Magna Carta and a quill pen. Historians were outraged, because John never “signed” the document as the coin—and countless other images—depicted. At the time, documents were authenticated with the application of a seal. There was no single Magna Carta, either; royal scribes had made dozens of copies (between 13 and 40), which were all authenticated with John’s royal seal. Getting even more technical, you can take a look at what the Oxford English Dictionary says about the definition of “to sign.” According to them, that includes “to stamp with a seal or signet; to cover with a seal,” but the first known usage of the word in that way was in a document written by Henry III, John’s son. So, technically, the Magna Carta was never signed. Read More: Twitter