When an unidentified body is found, a skull can unlock the secrets of that person’s appearance, even after decomposition and the passage of time. Police have been using composite sketches to identify suspects and victims for around 100 years, but forensic sculptors take the recreation of faces to another level. Forensic sculptors will study the skull and measure the tissue depth to craft a replica of the subject’s face. The portrait, usually made of clay, will also include quirks such as broken bones and dentistry. Hair and eye color are largely guesswork, but the essence of a face can be reproduced with startling results. A forensic reconstruction is an art form that gives anonymous bodies their names back and lets us see the faces of ancient people and long-lost murder victims.

10 Chicago Jane Doe

A large cardboard box sat unnoticed in a Chicago alley until curious trash hunters looked inside and found human remains. The decomposed female body was discovered in January 2007 but could not be identified, so police named her “Chicago Jane Doe.” Leading forensic artist Karen Taylor was tasked with making a facial reconstruction from the skull. The victim’s hair and ponytail elastic were still visible, and she also had a distinctive chipped front tooth plus orthodontic bands leftover from recent treatment. A photo of the sculpture—along with dental X-rays—was featured in the Illinois Dental News, and a receptionist remembered the victim from visits to their office. The patient’s name was Marlaina “Niki” Reed, a 17-year-old who had disappeared from foster care, and DNA confirmed her identity.[1]

9 Cheddar Man

Deep inside a limestone cave in Cheddar Gorge, England, the body of a man lay undiscovered for nearly 10,000 years. The skeleton was found during excavations in 1903 and put on display at London’s Natural History Museum as an example of a Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) man. Cool temperatures inside the cave had preserved his precious DNA, and in 2018, a team from the museum took samples from the petrous (inner ear bone) of Cheddar Man to learn more about his origins. His DNA revealed a 76% chance that he had light blue eyes and “dark to black” skin pigmentation, more commonly found in people from sub-Saharan Africa, not ancient Britain. Forensic artists measured and scanned the skull to construct a model of his face using this new information. Researchers had previously believed that early humans slowly developed lighter skin after migrating to Europe around 45,000 years ago. The arrival of farmers from the Middle East, combined with pale skin’s ability to absorb UV light in colder climates, brought about this change. Scientists always thought that light-colored eyes and blond hair evolved much later. The discovery of Cheddar Man with his blue eyes and dark skin turned this theory on its head.[2]

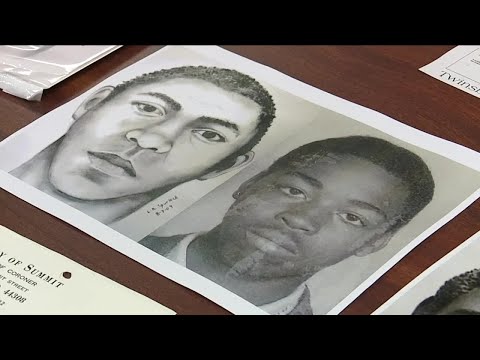

8 Twinsburg John Doe

Workers dumping trash behind an abandoned factory in Twinsburg, Ohio, discovered a skull and other body parts stuffed into a garbage bag. The victim had been stabbed, beaten, dismembered, then set alight in a determined effort to destroy his identity. An autopsy revealed he was an African American male aged between 20 and 35 years. Unfortunately, no one remembered the man, and his body, found in 1982, was named “Twinsburg John Doe.” Watch this video on YouTube In 2016, police appointed forensic artists to construct a clay sculpture of John Doe’s face using his skull and teeth, although the mandible (lower jaw) was missing. Images of his face were circulated with no results. In 2018, a match was found by the DNA Doe Project—a voluntary group that identifies human remains through genealogy databases. John Doe’s name was Frank Little Jr, a former soldier who had found fame as a guitarist and songwriter for the R&B group, The O’Jays. Little left the group in the late 1960s and lost touch with his family around the mid-1970s. What happened to him next remains unknown.[3]

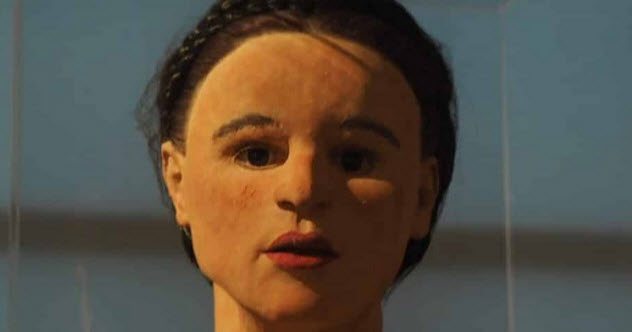

7 Jane from Jamestown

The Jamestown colony in Virginia was comprised of English settlers who arrived in 1607. The community faced drought, starvation, and disease, culminating in the bleak winter of 1609, known as the “Starving Time.” Watch this video on YouTube Historical documents state that extreme hunger drove the colony to eat horses, dogs, and even their own leather boots. Now evidence suggests that cannibalism saved the group from extinction. In 2012, archaeologists at James Fort, Williamsburg, found pieces of a human skull next to animal bones in a disused cellar at the camp. A CT scanner was used to reassemble the female skull. From this, a 3D facial reconstruction was created and named “Jane” by anthropologists from the Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural History. Jane was 14 years old, from Southern England, and had a high protein diet which suggests that she was from an affluent family. Clumsy puncture marks to the back of her head, which smashed the skull in half, indicate a desperate attempt to extract her brain, tongue, and cheeks—all unmistakable signs of cannibalism. The Jamestown teenager was not thought to have been murdered, but she is unlikely to be the only corpse cannibalized by the starving people of Jamestown.[4]

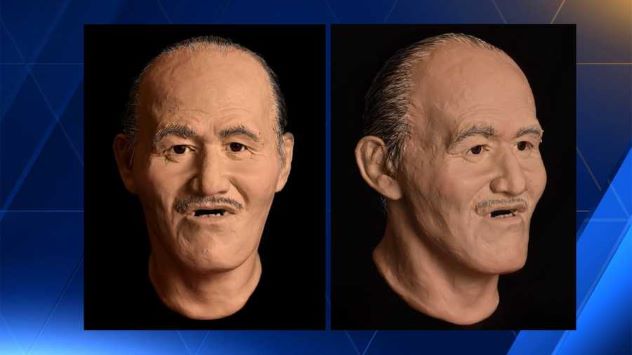

6 Pleasant Prairie John Doe

Walking near railroad tracks in Pleasant Prairie, Wisconsin, a photographer stumbled across a badly decomposed body. An autopsy found that the corpse was male, aged between 40 and 60, with long black hair and missing front teeth. A tattoo on the man’s forearm featuring leaves and a bear claw raised hopes that he would be identified, but no one recognized him. Further DNA testing revealed links to the Catawba Nation of South Carolina and family members in Mexico. After 23 years, John Doe’s skull was submitted for a full facial reconstruction. A clay model of the mystery man’s face was unveiled at a press conference in 2016, but his identity is still unknown.[5]

5 Spitalfields Roman Lady

London is a city steeped in history, and in the 1990s, major construction works unearthed an ancient Roman cemetery hidden under the streets of Spitalfields Market. One coffin stood out from the rest—made from valuable lead and adorned with seashells, it held the remains of a Roman A-lister who had died around AD 350. The perfectly preserved female skeleton was dressed in robes made from Chinese silk stitched with pure gold thread. Inside her coffin were jars of perfumed oil and a pillow of bay leaves to ease her journey to the afterlife. Further tests revealed she was born in Italy; it is believed that she came to Roman-occupied London as the wife of a centurion. In 2000, a facial reconstruction of the Spitalfields Lady was made from her preserved skull and is on display at the Museum of London.[6]

4 Boulder Jane Doe

Silvia Pettem was visiting Boulder’s Columbia Cemetery in 1996 and was intrigued by a simple grave that read “Jane Doe, Age About 20.” Pettem learned that the headstone had been paid for by the people of Boulder after a woman’s battered remains were found near a creek in 1954, her identity unknown. Pettem went back over old case files and autopsy reports in a bid to learn more and persuaded the police to re-open the case. Jane Does’s body was exhumed in 2004, and a forensic sculptor created a 3D model of her face after studying the skull. The great-niece of a woman who had disappeared from Phoenix in 1954 was also searching the internet—and found Pettem’s website. She believed Boulder Jane Doe could be her long-lost relative, Dorothy Gay Howard. The woman had left home at 18 and was never seen again. In October 2009, DNA tests confirmed it was Dorothy’s body. Police believe Dorothy fell victim to serial killer Howard Glatman who had hinted at a Colorado murder. Glatman was executed in 1959.[7]

3 Viking Warrior Woman

A Viking’s grave in Norway was filled with a deadly cache of weapons in honor of a hero. Experts believed that only Viking men went into battle, but the skeleton found in this warrior’s grave was female. In 2019, a team from the University of Dundee studied the 1000-year-old skeleton and discovered a deep crack in her skull, severe enough to damage the bone. The woman had survived a brutal sword attack, making her the first female Viking with battle scars equal to her male counterparts. Scientists layered skin on top of muscle to produce a detailed likeness of the 18-or-19-year-old’s face. The model—in all its gory detail with a swollen eye and bloody head wound—can be seen at Oslo’s Museum of Cultural History.[8]

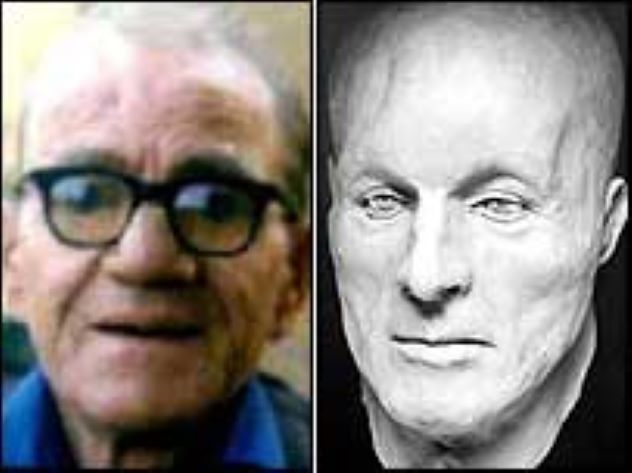

2 Body 115

Thirty-one people were killed at Kings Cross station, London, in November 1987 when a discarded cigarette landed on garbage piled under a wooden escalator, and fire engulfed the building. One victim remained unidentified. Named “Body 115” after his mortuary tag number, the man was 157.5 centimeters (5 feet 2 inches) tall and had recently undergone brain surgery. Hundreds of calls came in from the families of missing men, but none matched Body 115. Forensic artists took what remained of his skull and badly burned features to reconstruct his face. Alexander Fallon’s family always wondered if he had perished in the fire. Fallon had left Scotland after his wife’s death and drifted toward London, where he spent years living on the streets. His occasional letters home all stopped in 1987. Forensic experts compared skull measurements and confirmed that Body 115 was 72-year-old Fallon. Fallon had been buried in a shared grave with Ralph Humberstone, another recently identified victim. Fallon’s name has now been added to a memorial plaque, replacing the words “Unknown Man.” [9]

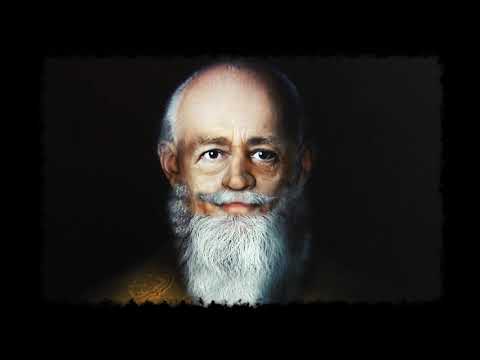

1 Santa Claus

How do you picture Santa Claus? Twinkly blue eyes and soft rosy cheeks? Wrong. The real St. Nicholas had deep brown eyes and an olive complexion with a heavy jawline and a broken nose. The journey to uncover St. Nicholas’s face started in the 1950s when his remains were exhumed from a crypt in Italy. Anthropologists took X-rays and detailed measurements of his skull. However, it wasn’t until 2004 that computer software existed to enable scientists to build a virtual clay model of his face. A team from Manchester University in the UK created the 3D image using just these recorded measurements. His eye color and skin tone were matched with people living in the same area of Asia Minor, now Turkey. Studies of religious art from the 4th century—when St. Nicholas was Bishop of Myra—found that he probably had the same white hair and beard as our modern-day Santa. Over the years, this Greek bishop has somehow morphed into the red-suited man from the North Pole we all know and love. His new name “Santa Claus” comes from the Dutch feast day celebration of St. Nicholas—Sinterklaas.[10]