So scientists have to get crafty (and a little lucky) to uncover prehistory’s culinary secrets. Still, they have found some interesting ones, which could change the way we view prehistoric people. They appear to have been more advanced than we thought.

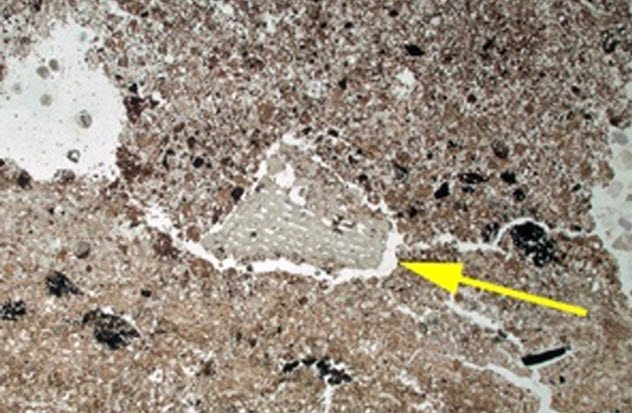

10 Paleolithic Processed Flour

“Cavemen” were eating wild oats long before the agricultural revolution according to some amazingly old residue detected on a 32,000-year-old pestle-like grinding stone. That makes it history’s oldest oatmeal. It was made through a four-step process that probably involved heating and milling, the earliest evidence of a four-step process used to prepare plants. The procedure yielded oat flour, which they then boiled or baked into flatbreads. Ancient groups like these might have been eating and processing grains even earlier, inspiring increased scrutiny of similar stones in search of more history-altering residue.[1]

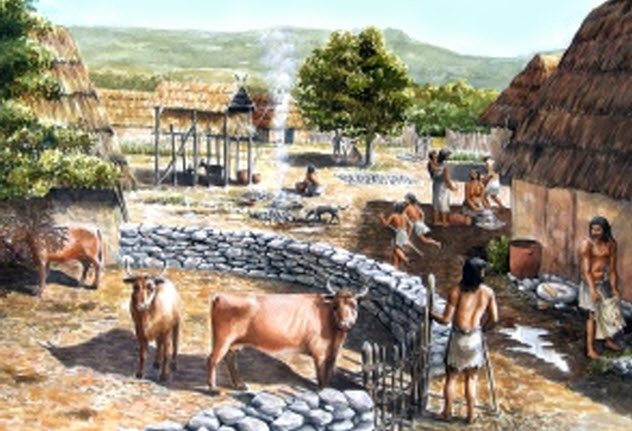

9 Cheese For The Lactose Intolerant

A 7,500-year-old piece of pottery riddled with holes stumped scientists until biochemical analysis revealed dairy fats, showing that the Neolithic people of 5500 BC had already mastered cheesemaking. Cheese, which involves separating milk into curds and whey by adding bacteria and rennet, was a game-changing item at that time. It provided food from animals while sparing the animals, increasing a group’s farming potential. It might also prove why humans domesticated cattle way back when most humans were lactose intolerant. Cheese products contained far less lactose than pure milk and didn’t upset sensitive Neolithic tummies. Plus it added a sorely needed supply of fats.[2]

8 Surprisingly Rich Paleolithic Pantries

Vegetables don’t age well across millennia, so it’s almost impossible to tell what kind of plants composed the Paleolithic menu. But if said vegetables become saturated with water, the oxygen deprivation can preserve them. Researchers at a dig in northern Israel found vegetables like these and many more than they expected our ancient ancestors to be eating nearly 800,000 years ago. The team found at least 55 types of plants, including nuts, seeds, and roots. The site also revealed the oldest incidence of controlled fire in Eurasia, which was necessary to turn most of these toxic plants into edible products. But the ancients did supplement their diet with a bit of meat and fat, even an elephant brain discovered at a previous dig.[3]

7 Fossil Poo Reveals Relatively Healthy Neanderthals

Sometimes, archaeology is funny, like when researchers crush up 50,000-year-old Neanderthal poo to detect its intrinsic colors. Via spectroscopic analysis, fossilized feces (coprolites) have finally revealed the scope of the Neanderthal diet. As the foods were no longer intact when expelled from the Neanderthals, scientists looked for signature compounds that form when bacteria help break down meats and veggies. Neanderthals ate a fair amount of big game meat, including reindeer and mammoth, but also introduced an assortment of plants to balance their diet. This discovery may rule out a Neanderthal extinction scenario in which they chronically gorged themselves to death with a meat-centric menu.[4]

6 Ancient Toothpicks

Even with the healthiest diet, cavities are inevitable. But it didn’t always mean the end of a Paleolithic person’s eating career because some had access to dentists. Researchers pushed tooth care back a few thousand years again with the unearthing of a 14,160-year-old skeleton with signs of dental work. The skeleton belonged to a 25-year-old who had suffered a cavity but had it picked out with a flint instrument. So, at least some Paleolithic people knew that cavities could lead to infections and dealt with them, painfully but effectively, before they could cause more grievous bodily harm. The Paleolithic people were also compulsive toothpickers, and the study explains all the wooden and bone-hewn picks found previously.[5]

5 Homo naledi’s Gritty Culinary Niche

Over 300,000 years ago, a number of hominins inhabited southern Africa and competed for resources. One of these hominins, Homo naledi, found a culinary niche by eating grit. Dental mapping revealed that Homo naledi’s teeth were mostly similar to those of Australopithecus africanus and Paranthropus robustus, but they were longer, more wear-resistant, and consistently chipped. The wear and tear suggests that Homo naledi subsisted on grittier food sources, either those covered in dust or dirt or rough plants fortified with silica. These compounds, known as phytoliths or plant stones, protect plants from browsing animals. But some developed high-crowned molars to resist the grit, and Homo naledi may have done the same to exploit a neglected food source.[6]

4 History’s Earliest Barbecue

Our ancestors first walked upright six or seven million years ago, but it was another five or so million years before the much fatter-brained Homo erectus emerged. Researchers believe that the critical spark came in the form of cooking because it gave us easier access to more digestible food sources. The earliest evidence of a cookout comes from South Africa’s Wonderwerk Cave. Analysis revealed a twig and grass fire from about a million years ago as well as grayed bone fragments. The location, deep inside a cave, quashes the possibility that the ash was swept in by wind or water. Pot-lid flakes, or fire-chipped stone fragments, were also found, suggesting repeated fire use at the site.[7]

3 Saharan Veggie Hot Pot

Cooking directly over fire served the early hominins fine but produced gritty, ashy food. The next step in culinary evolution was the use of cooking pots to improve food variety and quality. Humans made the first clay pots in the Far East about 16,000 years ago, but pots weren’t used to prepare food until around 10,000 years ago according to finds from the Libyan Sahara. Back then, grasslands, rivers, and lakes covered a verdant Sahara. And the residue from the pots shows that humans ate just about everything green, be it leaf, grain, seed, or even aquatic plants dredged from Saharan watering holes.[8]

2 Mesolithic Mustard

After our ancient ancestors balanced their diet, their next culinary innovation was to make it tasty. They accomplished this more than 6,000 years ago with one of the world’s most widely enjoyed condiments, mustard. Not plain mustard, mind you, but garlic mustard. Numerous Mesolithic cooking pots found in Germany and Denmark still retained residue from mustard seeds and leaves. Researchers believe that our ancestors mashed the mustard seeds into their dishes and added the garlic-flavored leaves for a one-two flavor punch. The discovery represents the shift between the consumption of food solely for its caloric or nutritive value and the more modern modes of hedonistic eating.[9]

1 Ancient Tortoise Appetizers

Qesem Cave in central Israel remained undisturbed for eons until road builders accidentally rediscovered it in 2000. Inside, researchers found an old habitation and a 400,000-year-old appetizer, tortoise. The tortoises were butchered with flint knives and roasted in their shells. But they probably weren’t the main course because the prehistoric hunter-gatherers that occupied Qesem Cave for 200,000 years supped on a varied, rich diet. They likely enjoyed tortoise as an appetizer, side dish, or dessert in addition to an assortment of vegetables. The main course consisted of much heartier game, including ox, deer, and horses.[10]