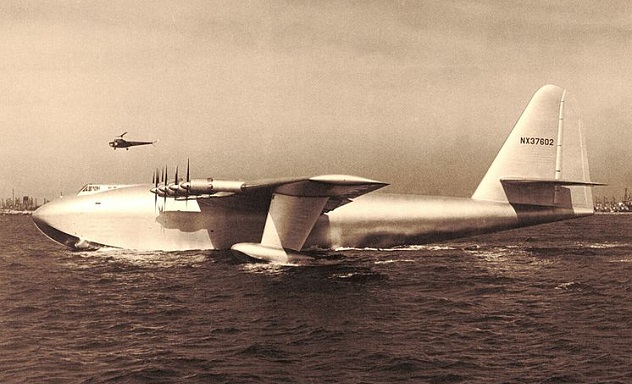

10 Blackburn B-20

During World War II, floatplanes and flying boats played a big part in the air forces of the world powers. Floatplanes had the advantage of being more flexible in water operations, but they were often small and struggled with maneuverability due to the large float on the bottom of the plane. Flying boats were often used as patrol bombers, but they were large and slow. So the Blackburn Aircraft Company decided to design an airplane that joined the best elements of floatplanes and flying boats, ending up with the oddball B-20 (somewhat similar to the one depicted above). Half of the B-20’s fuselage was a retractable float. When the B-20 went to land on the water, the lower part of the fuselage would descend into the water. This configuration would give it more versatility in combat, and it would also increase the wing incidence to give it a shorter takeoff run. As soon as the B-20 was in the air, the fuselage would join back together, making it look like a small flying boat. In this configuration the B-20 had much less drag than other flying boats, giving it unprecedented speed. However, during a test flight, the B-20 fell apart and crashed, killing some of the crew. The British Air Ministry realized that it was a fluke. The concept of the B-20 was sound, but as Blackburn focused its attention to building preexisting airplanes, the need for its experimental aircraft dropped. Nothing ever came from the B-20.

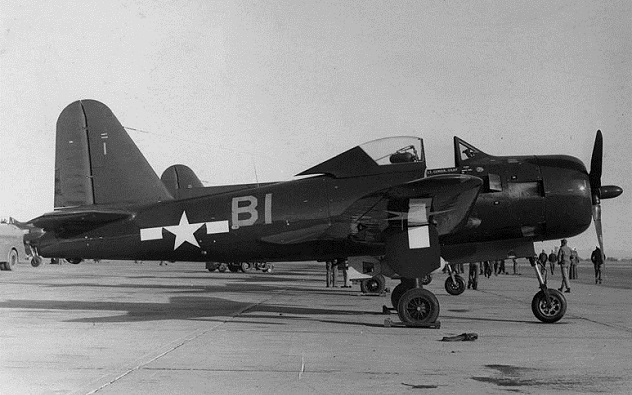

9 Ryan FR Fireball

Compared to Germany and the United Kingdom, the United States ended up behind the curve when it came to building and adopting effective jet aircraft. The first jet fighter in the United States was the dismal P-59, which was not any better than a propeller-driven aircraft. At the same time that Bell built the P-59, the Navy was working on the FR Fireball, a fighter which used an odd power plant system. Instead of just having a jet engine, the Fireball used a propeller in the front and a jet engine in the back. Since early jet engines had sluggish throttle response, the Navy considered them too dangerous for carrier operations. During most operations (specifically landing and takeoff), the Fireball used its propeller engine, but when they needed extra thrust, the pilots activated the jet engine. Other than that, the Fireball was a highly conventional airplane, coming out as basically a normal fighter plane with a jet engine strapped to the back. Although it entered service in March 1945, the Fireball never saw combat service. Ryan only built 66 Fireballs, and they were quickly replaced by the next generation of jet fighters. In addition to poor range, the plane was also hurt by its lackluster performance, as Fireballs were slower than many planes even when using the jet engine. Despite the flaws, the Fireball was an important step for the Navy. It was their first jet airplane. The Fireball also was the first airplane in the world to land on an aircraft carrier under jet power . . . albeit accidentally. When a pilot’s prop engine failed in 1945, he was forced to land on the USS Wake Island under jet power.

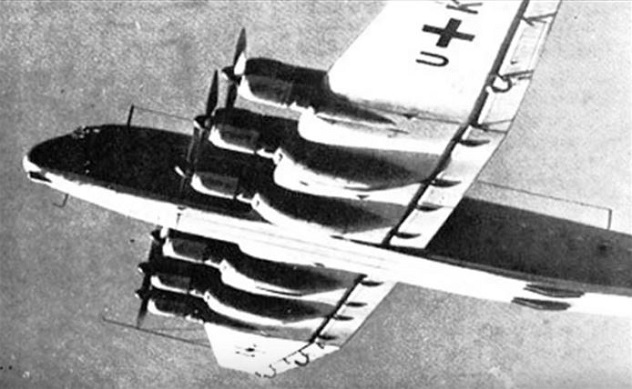

8 Blohm & Voss BV 238

The aerospace company Blohm & Voss designed most of the Luftwaffe’s flying boats during World War II. As the war progressed, the company’s engineers designed even more complex and large flying boats. Ultimately, this culminated in the BV 238, a behemoth flying boat that was the biggest airplane designed by the Axis powers during the war. Blohm & Voss built the BV 238 in 1944, intending for it to offer the Luftwaffe long-range transport capabilities. Luftwaffe commanders also investigated the possibility of using the giant flying boat as a long-range patrol bomber. Flight testing showed that the airplane was stable and could perform the transport role effectively. Disaster struck for the flying boat when three American P-51 Mustangs found the prototype docked at Lake Schaal. Lieutenant Urban Drew attacked the boat, causing tremendous damage to the fuselage. Before the German engineers could save the BV 238, it sunk to the bottom of the lake. With the war turning in the Allies’ favor, Blohm & Voss discontinued work on the airplane. As for Lt. Drew, he became something of a legend. After all, he set the record for “biggest Axis airplane ever destroyed by an Allied pilot.”

7 Flettner Fl 282

Most people do not think of the helicopter as being a weapon of World War II, but while the fighting nations were rushing to develop jet propulsion, they were also working on the first generation of helicopters. As with jet propulsion, the Germans held an early lead over other nations. They experimented for years with helicopters, but it was not until the Fl 282 that they had a design that could be be mass-produced. Flettner designed the Fl 282 with the odd feature of intermeshing rotors. This meant the two main rotors angled away from each other, but the arc of the blades crossed. In other words, they were carefully synchronized to avoid disaster. The intermeshing rotors gave the helicopter the advantage of not needing a tail rotor to offset the torque from the main rotors. Other than that weird feature, the Fl 282 was a bare-bones design, just minimal framing attached to an engine. The Luftwaffe was so impressed by the Fl 282 that they ordered 1,000 choppers. Possible roles for the helicopter included anti-submarine warfare, naval spotting, and reconnaissance. However, by the time production was ready in 1944, the Luftwaffe was already fighting on the defensive, and the fleet of Flettner helicopters never materialized. Flettner only completed a few models, but these were well received by pilots. Nevertheless, shortly after production started, an Allied bombing raid destroyed the production plant, ending any possible production of the helicopter. The engineer behind the project, Anton Flettner, immigrated to the United States where he helped design excellent helicopters for the United States Air Force.

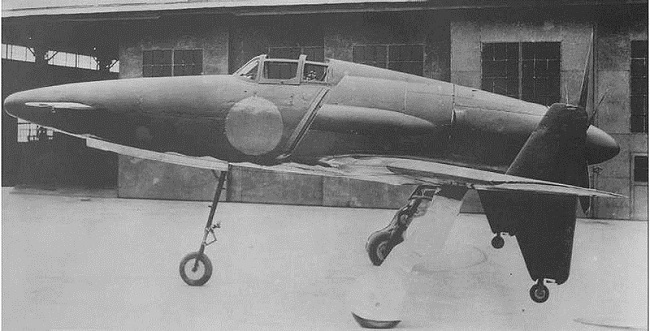

6 Kyushu J7W

One of the most futuristic-looking airplanes of the era was the Japanese-designed J7W Shinden, an airplane with a canard design. That refers to a plane with the “main wing mounted at the rear of the fuselage and a smaller wing fixed to the front.” The hope is that with this innovative layout, the J7W would be highly maneuverable and able to fight American B-29 bombers. The interceptor had a big engine that drove a six-blade pusher propeller by an extension shaft. During testing, the engine caused a lot of problems as it was prone to overheating, even when tested on the ground. By the time the war ended, the Kyushu engineers figured out most of the problems with the engine. To take down the B-29 bombers, the J7W carried four 30mm cannons, making it one heavily armed aircraft. Japanese Navy officials had such hope in the J7W that they ordered production before the first prototype even got off the ground. Fortunately for the B-29 crews, the J7W only completed three test flights before the war ended, and the plane never entered production. Even during testing, the J7W barely got any flight time, only clocking a combined 45 minutes in the air over three test flights. The war ended before the Navy could perform other tests on the airplane. A proposed turbojet version of the airplane never left the drawing board.

5 Heinkel He 100 And He 113

As the Luftwaffe geared up for World War II, they looked at a variety of airplanes to replace their primary frontline fighter plane, the Messerschmitt Bf 109. The leading competitor for the design was the Heinkel He 100, one of the best airplanes in the world at the time. Although it is difficult to find wartime documents about the He 100, it is clear that the plane was a significant improvement over the Bf 109 and had a variety of characteristics that would have made it an effective airplane against Allied pilots. Most impressively, the He 100 broke and held the world speed record for an airplane of its class. However, for some reason, the Luftwaffe decided to continue development on the Bf 109 and its variants. Nobody knows exactly why the He 100 project stopped Even though the He 100 never reached frontline service, it played a fascinating role in early propaganda efforts. When the war began, the United Kingdom did not have adequate information about the Luftwaffe, including what types of airplanes it flew. Taking advantage of the situation, Joseph Goebbels announced that the Luftwaffe was fielding a new He 113 fighter, but in reality, it was just a repainted He 100 prototype. German publications often featured pictures of the “new fighter,” accompanied by reports of its combat abilities. These reports made it to the UK where the Royal Air Force became concerned about the He 113. Until 1941, pilots reported facing the airplane, but there was no proof that their stories were accurate. Eventually, the Air Ministry figured out that the Luftwaffe was tricking them and that the He 113 didn’t exist.

4 Fisher P-75 Eagle

During the early part of World War II, the United States hadn’t yet developed the fighters that would later aid them against the Luftwaffe. Most of these planes, like the P-51 and P-47, were still under development and hadn’t reached their peak performance. Because of that, the Luftwaffe generally had the advantage in terms of air power. To counter Luftwaffe airplanes, the United States Army Air Force began looking for a high-speed interceptor fighter with heavy armaments. The Allison engine company saw this as a chance to show off their new V-3420, a huge 24-cylinder engine that was actually two V-1710 engines mated into one. Allison and the Fisher Body Division of the General Motors Corporation worked together to make a new airplane around the engine. Oddly, Fisher decided to build the P-75 with preexisting parts. The P-75 was a mixture of other successful airplanes, including the Dauntless dive bomber and a variety of fighters including the P-51 and P-40. The huge engine was located in the middle of the airplane, driving the two contra-rotating propellers by a drive shaft. Of course, it should come as no surprise that making a fighter plane by combining parts from preexisting airplanes does not work. The P-75 was slow and sluggish in its interceptor role, causing the Air Force to pass on the design. Fisher then tried to advertise the P-75 as a long-range escort fighter for bombers, but by that time, better fighter planes were available, leaving Fisher to stop development on the P-75.

3 Bereznyak-Isayev BI-1

Most major countries in the world experimented with rocket-powered airplanes during World War II, the most successful being the German Me 163 Komet interceptor. But lesser known than the Komet is the Soviet experimental rocket fighter, the BI-1. In the late 1930s, Soviet officials wanted a fast, short-range defense fighter powered by a rocket. The need for such a plane became especially pronounced as German forces began to invade Russia. Engineers completed plans for the rocket plane by spring of 1941, but Stalin did not give authorization to build a prototype. However, when the German invasion began, Stalin told engineers Alexander Bereznyak and Aleksei Isayev to get the airplane ready as soon as possible. It took only 35 days to complete a working prototype. Getting just under the deadline, a bomber towed the BI-1 aloft, allowing it to glide to the ground for a first test. Rocket motor tests commenced in 1942, but powered flights quickly revealed that the BI-1 only had 15 minutes of flight time from the moment the pilot ignited the rocket on the ground. This proved a severe limitation. When the third prototype disintegrated midair during a level flight, the engineers realized that there was another problem. The frame, made of plywood and metal, was not designed for nearly supersonic speeds. Research on supersonic aerodynamics was still in its infancy, and the BI-1 airframe was not designed to perform at those speeds without falling apart. Quite simply, the BI-1 was too fast for its own good. With that limitation, testing ground to a halt, and the war turned in favor of the Soviets, ensuring that there was no further development of defensive rocket planes.

2 Junkers Ju 390

Although they did not realize it at the time, the Luftwaffe made a serious error when they refused to develop any long-range heavy bombers. By the middle of the war, the Royal Air Force and United States Army Air Force were conducting raids into German airspace, causing mass destruction to the German war industry. That’s when Luftwaffe commanders realized they needed a heavy bomber, specifically one that could strike the United States. Thus the “America Bomber” project was born. The Luftwaffe considered many different designs for the project, but one of the most feasible was the Junkers Ju 390. Junkers, a German company, developed the new bomber from their existing Ju 290 heavy transport. The new bomber had six engines and was capable of a transatlantic flight. Test flights commenced in 1944, and they showed the Ju 390 was an effective and powerful machine. However, by that time, the Luftwaffe was on the defensive, and any offensive bomber projects were given low priority. Junkers only could finish two prototypes by the time the war ended. Mystery and conspiracy shroud the Ju 390 tests and operations. According to some sources, one of the prototypes flew from Germany to South Africa on a test flight. Some wartime reports show that the bomber was also test flown over the Atlantic Ocean, entering United States airspace before turning back. Fringe conspiracy groups also believe that a Ju 390 flew to Argentina at the end of the war, carrying secret weaponry for escaped Nazis. Whatever the case, the Ju 390 was the closest the Germans ever came to developing a bomber that could reach the United States.

1 Northrop N-9M

During the ’30s and ’40s, famous aircraft designer Jack Northrop worked tirelessly on his idea for flying wing airplanes. Northrop hoped to build high performance airplanes that consisted only of a giant wing, eschewing traditional airplane engineering. At the beginning of World War II, Northrop convinced the United States Army Air Force to fund his research into flying wings with the hope of creating a bomber based on that configuration. They agreed to fund his research, so Northrop went ahead and built a small test airplane to investigate the feasibility of a flying wing bomber. Named the N-9M (“M” for “model”), the airplane was small and light. It had a boomerang shape with no vertical control surfaces. Power came from two pusher propellers. The N-9M took some getting used to, but it was a good airplane once the pilot adjusted. During testing, one fatal crash occurred, but that did not deter Northrop. By the end of the war, he had enough research to build his flying wing bomber, the XB-35. Unfortunately, with the war over, the Air Force did not have much interest in the bomber or its jet-powered cousin, the YB-49. The project ended in the late 1940s. Even though the original flying wing bombers never came to fruition, the Air Force began using the B-2 stealth bomber years later. To design this airplane, Northrop used a lot of the research he developed while working on the N-9M, making this World War II plane the predecessor of the famous B-2. Currently, one of the N-9M prototypes is still flying, making regular appearances at air shows and other events. Zachery Brasier is a physics student who loves aviation history and likes to write on the side. Check out his blog at zacherybrasier.com.