10 Wuthering Heights (1847) by Emily Brontë

In a 2007 poll conducted by UKTV Drama to find the greatest love story ever written, Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights came out on top, despite not actually being a love story. In reaction, journalist Martin Kettle accurately commented: “If Wuthering Heights is a love story, then Hamlet is a family sitcom.” Wuthering Heights has long been thought of in the same vein as Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813), but while the latter is definitely a romance novel, the former is actually a gothic tragedy. Heathcliff and Cathy do love each other, but their relationship is abusive in nature. Where Austen’s Mr. Darcy is an aloof but noble romantic lead, Brontë’s Heathcliff is cruel, obsessive, and sadistic. Heathcliff and Cathy’s relationship may have the passion expected of a great love story, but it is ultimately dark and destructive.[1]

9 Fahrenheit 451 (1953) by Ray Bradbury

Fahrenheit 451, which is set in the future where “firemen” are employed to burn books, is often interpreted as being about the dangers of state-enforced censorship. However, Bradbury himself believed that this missed the point. He proclaimed that the novel is “not about censorship, it’s about the moronic influence of popular culture through local TV news, the proliferation of giant screens, and the bombardment of factoids.” While it may be a bit strong to state that it is not about censorship at all, many people overlook the role that television plays in the novel. To Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451 is really about the mind-numbing effect of TV, which, in the novel, turns people away from literature. As LA Weekly reports, Bradbury was vehement about this and once even “walked out of a class at UCLA where students insisted his book was about government censorship.” In the world of Fahrenheit 451, the issue is that the population allowed book burning to happen by becoming unhealthily captivated by television rather than the government forcing it upon an unwilling populace.[2]

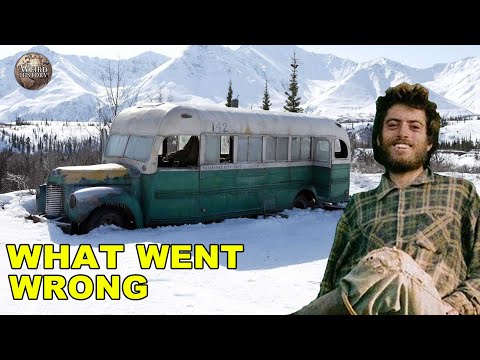

8 Into the Wild (1996) by Jon Krakauer

Into the Wild tells the true story of Chris McCandless, who took off after graduating from university to live a nomadic lifestyle while traveling across America. He then attempted to live off the land in the Alaskan wilderness but was ill-prepared and ended up starving to death in an abandoned bus on the Stampede Trail. McCandless stirs up opposing opinions: some view him as an inspirational figure of freedom; others believe he was merely foolish. Watch this video on YouTube Regardless of how McCandless himself is viewed, his story stands as a warning of the dangers of the wild. Despite this, many people have attempted to follow in his footsteps by making a pilgrimage to the bus where he spent his final days, ignoring the obvious risks of doing so. As a result, 75% of rescue operations in Denali National Park occur on the Stampede Trail. Baffled by this phenomenon, an anonymous park trooper asks, “What would possess a person to follow in the tracks of someone who died because he was unprepared?” Countless people have been rescued after winding up in perilous situations, and at least two people have died, prompting the removal of the bus in 2020.[3]

7 Fight Club (1996) by Chuck Palahniuk

Many people read Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club or watched David Fincher’s 1999 film adaptation and understood that it was intended as an anti-capitalist satire. Others, however, took the violence depicted in the novel and on screen as a blueprint for dealing with their disenchantment with the world. Paulie Doyle, writing for Vice, explains that Fight Club has “been embraced by the loose collection of radical online male communities (known as the “manosphere”) as a kind of gospel text.” Watch this video on YouTube Palahniuk believes that the distortion of his novel just “shows how few options men have in terms of metaphors: a skimpy inventory of images.” By twisting Fight Club into validation for their hostile philosophy, these groups completely miss the point of the satire. Tyler Durden is not supposed to be a celebrated hero or a model of masculinity; he is an example of a dangerously extremist reaction to the problems of the world.[4]

6 Oedipus Rex (429 BC) by Sophocles

When most people hear the name Oedipus they think of Sigmund Freud’s Oedipus complex, a now largely criticized psychoanalytic theory proposing one of the stages of childhood development involves a child wanting to have sex with the parent of the opposite sex and hating the parent of the same sex. This theory got its name from the myth of Oedipus, best known through the play by Sophocles. This has led some people to believe that Oedipus wanted to sleep with his mother and kill his father, but the opposite is actually true. Watch this video on YouTube In Sophocles’s play, Oedipus receives the prophecy about his mother and father and attempts to evade his fate. No one can outrun fate in a Greek tragedy, though, and Oedipus ends up killing a stranger who turns out to be his father and marrying a woman who turns out to be his mother. Far from desiring these things, as in Freud’s theory, when Oedipus learns the truth, he gouges his own eyes out and declares, “if there is a woe surpassing all woes, it has become Oedipus’ lot.”[5]

5 On the Road (1957) by Jack Kerouac

On the Road is one of the foundational texts of the Beat Generation—an American social and literary movement originating in the 1950s—but Jack Kerouac thought that his most famous work was largely misunderstood. Under the thin guise of fiction, On the Road chronicles his travels across America and includes a heavy dose of sex and drugs, but he never intended to glorify this lifestyle. In a 1968 interview, Kerouac stated that the Beat movement was now “apparently some kind of Dionysian movement,” which he “did not intend.” He believed that most Beatniks had missed the spiritual element of the novel. Historian Douglas Brinkley edited Kerouac’s diaries and emphasized this spiritual side of Kerouac’s journey, pointing out that on “almost every page, he drew a crucifix or a prayer to God, or ask[ed] Christ for forgiveness.” Brinkley further states that On the Road is not about reckless hedonism; rather, it “is a lesson about the continued need for self-discovery.” Kerouac spoke out against Beatniks siphoning down his exploratory novel into something unrecognizable, but to this day, many people associate it with nothing but pleasure-seeking.[6]

4 The Prince (1532) by Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò Machiavelli has long been associated with evil behavior, thanks in large part to a misunderstanding of the political theory he lays out in The Prince. This guidebook for rulers does recommend cunning behavior but only in certain limited situations, not in the blanket “the ends justify the means” way in which it has become known. Watch this video on YouTube Machiavelli’s pragmatic ideas being distorted and turned into pure evil were aided by people who were repelled by his disregard for Christian ideals. For instance, Innocent Gentillet’s 1576 work, which became known as Anti-Machiavel, portrayed Machiavelli as a “wicked Atheist.” His villainous reputation was further cemented by the stage Machiavel, a character in Renaissance drama who is a caricature of his ideology. Some people did engage with Machiavelli’s actual philosophy, but to this day, most people still associate his name with evil.[7]

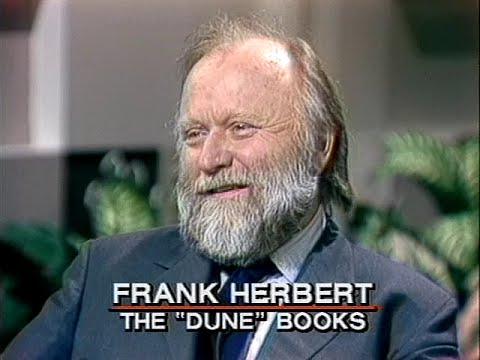

3 Dune (1965) by Frank Herbert

Frank Herbert’s sci-fi classic follows Paul Atreides on what seems to be a version of the hero’s journey or The Chosen One narrative. Spoiler warning: Herbert takes that initial expectation and completely twists it. Likely, anyone who has only consumed Dune through David Lynch’s 1984 film adaptation or the 2000 miniseries believes that Paul is a straightforward hero. On the other hand, Denis Villeneuve’s 2021 film understands that Herbert’s novel is actually about how overzealous belief in leaders has dangerous consequences. Watch this video on YouTube Paul eventually becomes the Kwisatz Haderach, a clairvoyant superbeing who is hailed as a messiah. That sounds cool, but it turns out to be terrible for a lot of people. “Don’t trust leaders to always be right” is the book’s message, according to Herbert. He goes on to say that he created Paul as a leader who was “an attractive, charismatic person, for all the good reasons, not for any bad reasons.” Despite his good intentions, Paul’s power and sway over his followers have disastrous consequences: “Some of his decisions, made for millions of people, millions upon millions of people, don’t work out too well.” Dune and its sequels dig into the dangers of powerful, charismatic leaders who inspire fanatical loyalty.[8]

2 The Great Gatsby (1925) by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Great Gatsby conjures up images of glitzy Roaring Twenties parties overflowing with stylish flapper dresses and coupes of champagne. But anyone who has actually read the novel knows this is an empty façade, below which lies a deconstruction of the American Dream. This is not just a recent problem, as shortly after the novel’s publication, F. Scott Fitzgerald told his friend Edmund Wilson that “of all the reviews, even the most enthusiastic, not one had the slightest idea what the book was about.” The extravagant imagery associated with the novel has even inspired Great Gatsby-themed weddings. While the Roaring Twenties itself is not a bad theme, making a wedding explicitly Gatsby-themed is an odd choice given Gatsby’s shadiness and Daisy’s self-absorption. Their relationship leads to the deaths of multiple people, including Gatsby himself, so a wedding themed around the couple has pretty negative connotations beyond the gold glitter decorations.[9]

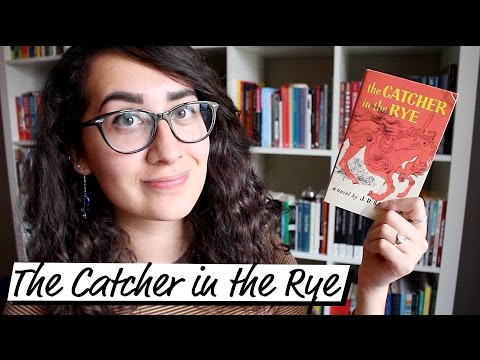

1 The Catcher in the Rye (1951) by J. D. Salinger

In recent years J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye has received a lot of hatred, primarily because people think that Holden Caulfield is whiny. An Electric Lit article proclaims, “if you’re a white, relatively affluent, permanently grouchy young man with no real problems at all, it’s extraordinarily relatable.” To say that Holden has no real problems is entirely inaccurate, though, and these problems are the direct cause of his irritability. Holden’s struggle with the phoniness of the world is brought on by the death of his younger brother, which plunges him into severe depression, which in turn causes him to fail almost all of his classes and be expelled from school. These are pretty serious problems for a teenager to be dealing with, and he receives almost no support. E. Ce Miller, writing for Bustle, states that “Holden’s story remains largely misunderstood by those who critique his character.” This is not to say that he is a likable character (that’s up for debate), but he is often misunderstood by readers who simplify his mental health issues as mere teenage angst.[10]