10 Profiting From The Dead

A newspaper report published in 1900 detailed a photographer who photographed dead soldiers after US Civil War battles. On one of his grisly adventures, the photographer visited the battlefield at Antietam three days after the eponymous battle, which was considered one of the deadliest days of the Civil War with over 22,000 casualties. The battlefield was littered with bodies to photograph. The photographer, who was not named in the article, said: It would be useless to go over the scene of that carnage again to tell of the ghastly after sights of that awful fight, which made so many widows and orphans. I was nervous and excited [ . . . ] when I unwittingly planted one leg of the camera stand on the chest of a dead union drummer boy. By some means he had been partly buried in a patch of soft soil. Nothing was visible but the buttons of his blouse and one foot. The man took his photographs and later printed them. He said the photographs “sold like wildfire at 50 cents and one dollar each. I was nearly $2,000 in pocket in less than two weeks.”

9 Posing Dead Bodies

In the late 1800s, a photographer moved to Chicago, hoping to make the big bucks. His dream of big city success was short-lived, and he soon found himself broke and his photography business almost dead. In a desperate effort to drum up business, he started reading the death columns in the newspapers. He then packed up and visited neighbors who had just lost someone and offered to photograph the deceased. Business suddenly picked up, and before long, he gained a reputation for posthumous photography. He related some of his more gruesome stories to a newspaper, saying that on one occasion he had to wait around until the father finally passed on: “Half an hour after the old gentleman breathed his last, and before he became stiff we had him sitting in a chair, with his eyes held open with stiff mucilage between the lids and the brow, and his legs crossed.” In another case, he had to take a body out of an icebox and prop it up for a photograph. He said the resulting picture was ghastly, but the family was happy with the results. The photographer explained that he would fill the recently deceased’s cheeks with cotton to make their faces look plump. He would prop their eyes open with pins or mucilage. In the worst cases, a photograph was taken, and an artist was hired to paint on the eyes and cover up any severe skin issues.

8 Photographing The Eyes Of The Murdered

A newspaper article published in 1904 contains a particularly interesting passage: “It has long been supposed by the uninstructed that the eye of, say, a murdered person retains the image of his assailant. Furthermore, it is believed by many that from the dead eye a photograph of the assailant might thus be procured.” It was an intriguing theory for the time, but did anyone ever try it? In 1885, police in Kansas City actually tested this wild theory. A photograph was taken of Katie Conway’s eyes. She had been found murdered, and the detectives were clueless as to who the murderer might have been. The plan was to place the photograph under a microscope “to see if the picture of the man who dealt the death blow can be seen.” Of course, nothing came of their experiment.

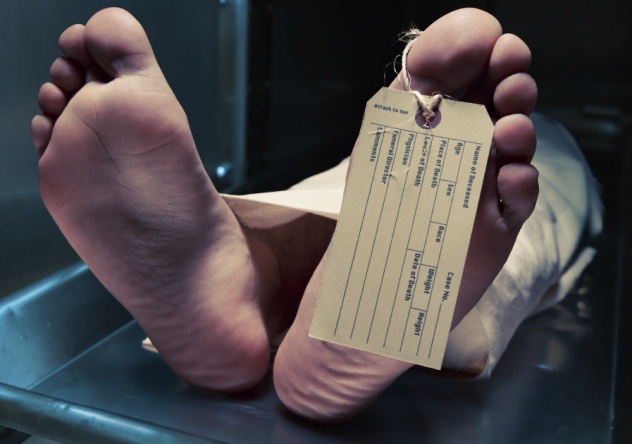

7 The New York Morgue

In the late 1800s, after seeing innumerable unidentified bodies go to the New York morgue, the superintendent of the Bellevue hospital “invented” the idea to photograph the unknown dead before they were sent to the “dead house.” By the fall of 1885, there was “a gallery of these pictures numbering over 600.” The negatives were kept safely filed away in case any friends or relatives were able to identify the bodies and wanted a keepsake copy of the death photo. For some families, it would be the only photograph they would ever have of the deceased. There were cases where the bodies were so badly injured or diseased that identification via photo might have been impossible. Clothing was noted in a book and kept for up to three months along with whatever was found in the deceased’s pockets. People who were searching for a missing person were assured that they would be “courteously received and assisted in every way to identify the lost.”

6 One Last Picture

A woman died on February 8, 1887. She was buried on February 21, but not long after that, her distraught husband wanted her dug back up and photographed. He told his friends about his plans, and his late wife’s mother heard about it. She begged him not to go through with his plan, but the man wouldn’t listen. In early March, the man “with the sexton and his assistants, went to the cemetery and began throwing the frozen earth from the newly made grave.” A crowd began to gather around the scene, and soon, his former mother-in-law was there, weeping and begging the man to stop the madness. The men in the crowd were angry at the sight and threatened the driven husband, but he still would not stop. Finally, the coffin was reached, the lid removed, and the coffin lifted out of the hole. A photograph was taken of the wife, and then she was returned to the ground to be buried a second time. The people of Avon, Michigan, believed the man to be crazy. One citizen was reported as saying, “We’ll yet make a black bird of him that’ll smell of tar.”

5 Ghouls And Camera Fiends

On September 8, 1900, Galveston, Texas was hit with a hurricane and major flooding, an event which became known as the Galveston Horror. It is estimated that anywhere between 6,000 and 12,000 lives were lost during and after the massive storm. Often, tragedy can bring out the worst in people. The military was brought in to clean up and restore order to the area. Their orders were to “kill any person caught in the act of robbing the dead.” The soldiers had to shoot 125 of these “ghouls.” Even worse were the “camera fiends,” who went around photographing dead people for profit. It was reported that guards caught and killed two photographers who “were detected in the act of photographing the nude bodies of dead women and girls. Their cameras were smashed by the soldiers and the negatives were destroyed.” The soldiers and the remaining survivors collected the bodies and burned them on funeral pyres to prevent the spread of disease.

4 Pinning On Clothing

As posthumous photography became a growing trend in the late 1800s, articles about photographing dead people flooded the newspapers. It was a morbid obsession that made people want to read about the secrets of the trade, and those who could afford the equipment found that they could earn quite a lot of cash posing dead people for photographs. In 1885, it was reported that photographers, like doctors and undertakers, had become insensitive to the dead. One article cited a photographer who was so used to his work that when a bit of drapery failed to hang correctly from shoulders of a posed body, “he took a big pin out of the end of his waistcoat and pinned the drapery to the flesh.” When his actions were called into question, the photographer pointed out that the dead body couldn’t feel a thing. Many people were uncomfortable with the idea that the dead were being disrespected, which is probably why more and more posthumous photographers began to advertise their compassion for the dead or insisted on posing the dead in private.

3 Photographing Death Itself

The idea of photographing death itself sounds like science fiction, but it was more likely a bunch of complicated baloney. In 1897, it was reported that a professor “succeeded in photographing death,” or more aptly, the moment when life left the body, using something he called “Kritik rays.” The professor went on to say, “The Kritik rays are directed out of a vacuum tube, and are so piercing that they almost immediately penetrate the body upon which for the purposes of experiment the investigator has turned them.” The professor claimed that the images produced on a photographic plate were different when used on living or dead tissue and believed that the Kritik rays would one day be used in all hospitals to determine with certainty whether a person was truly alive or dead. While the fear of being buried alive was perfectly understandable at the time, holding off on immediate burial seemed to be the easiest safeguard as opposed to finding out whether a person was truly dead or not.

2 Diagnosed With Necrophilism

In 1911, newspapers everywhere exploded with the story of the infamous poisoner Louise Vermilya. Because no one was able to fully believe that a healthy, sane woman would murder eight family members and one policeman, doctors tried to discover the root cause for her crimes. She was examined by several different physicians to find out what could be wrong with her and to determine if she had the “most horrible disease known to science”—“necrophilism” (aka necrophilia). At that time, if she were to be diagnosed with necrophilism, she wouldn’t have been held accountable for the murders and would have been sent to an asylum instead. Before her crimes were discovered, her neighbors and a few undertakers already knew that Mrs. Vermilya was fascinated with dead people. She volunteered to help take care of the dead and assist with the embalming process. When investigators searched her bedroom, called the “Death Chamber,” they found that her walls were covered with “photographs of the dead and of cemeteries.” Most of the photographs were of people and tombstones not directly associated with her. Her fascination with death had compelled her to buy the photographs and hang them on her walls. The coroner working on her case strongly believed that Mrs. Vermilya had a strong case of necrophilism, saying, “In no other way can I account for Mrs. Vermilya’s ghoulish delight in the dead and in things connected with death.”

1 The Innocence Of Babies

One of the most horrible experiences that parents can face is the loss of a child. In 1900, roughly 165 out of 1,000 infants died in their first year of life. Compare that to seven deaths per 1,000 in 1997. The loss of such young life was beyond horrible, and parents sought to cope with the loss in any way possible. One way to deal with the pain was to have the infant photographed. A photographer told a New York newspaper how he got his start in photographing the dead: I was new to the picture business then. I had been located for about two weeks in a studio [ . . . ] when a young woman came rushing into my office one morning, weeping piteously. The woman was bare-headed and she carried a bundle wrapped round with a blue shawl. She sat down in a chair by the window and began to rock the bundle to and fro gently. Presently she ceased sobbing and said: “I want a picture of my baby. Will you take it?” The photographer said he would take a photo of her child and asked her where the child was: For answer she unwound the shawl and revealed a tiny white face lying on her arm. The shock was so great that I actually staggered. “Why, good heavens, woman,” I cried. “The child is dead.” The young woman nodded. “I know it,” she said, “but I want his picture, anyway. Of course, I’ll never forget him, as it is, but I still want his picture to remember him by.” Elizabeth spends most of her time surrounded by dusty, smelly, old books in a room she refers to as her personal nirvana. She’s been writing about strange “stuff” since 1997 and enjoys traveling to historical sights.