While it’s likely that Odysseus lived only in the imagination of the poet Homer, there is at least a slight possibility that the Greek hero may have been real. And archeological discoveries like the site of Wilusa (Troy)—and possibly Ancient Ithaca—suggest to many modern scholars that the Homeric epics are actually the preserved memories of a very real war. If there’s even a shred of truth to the legend of Odysseus, then our boy sure got screwed. The King of Ithaca supposedly spent a decade fighting with the Greeks to (most likely) lift a Trojan blockade of Greek trade along the Hellespont. After the Greek victory and sack of Troy, it took Odysseus—who had incurred the wrath of the sea god Poseidon—another decade to find his way home. When Odysseus finally returned to Ithaca—ready to hang up his penis tie and relax—he wasn’t exactly congratulated on his hard work. Instead he found the nobles hanging out in his house and doing their very best to sleep with his wife. So the travel-weary Odysseus had to kill a roomful of his ungrateful aristocrats before he could finally kick back and (presumably) enjoy his favorite chair.

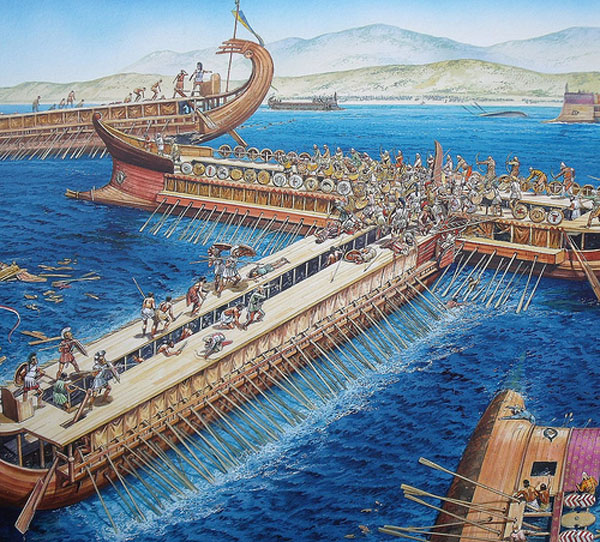

Despite what The 300 may have led you to believe, the Persian invasion was turned back, not at the mountain pass of Thermopylae, but at the naval battle of Salamis. In the narrow straits of Salamis a small Greek navy led by Admiral Themistocles inflicted a crushing defeat on the enormous Persian navy. With their nautical supply-line destroyed, the Persians could scarcely maintain the offensive on land. Unfortunately for Themistocles, many Athenians possessed a rather short memory and the great leader—a little like Winston Churchill—struggled to fit into life post-invasion. Themistocles was blamed for the growing rivalry with Sparta, was accused of treason, and then sentenced to death by his own people. He managed to escape from Athens, but while he was on the run the Athenians made him a scapegoat for all sorts of problems. Athenians questioned everything from Themistocles’ sexual practices (with one person referring to him as “Themistocles son of Neocles, a——hole”), to his loyalty. In the end, few choices existed for the exiled admiral. Themistocles sought refuge among his former enemies in Persia, where he lived out the remainder of his days.

Before Scipio took over, Hannibal Barca was mowing down Roman armies like crabgrass—and so it’s thanks to him that Rome did not become “New Carthage.” He brilliantly attacked the Carthaginian capital, forcing Hannibal to leave Rome alone and defend his own lands for once. His monumental victory earned him the moniker “Africanus” and the adoration of average Romans. But anyone familiar with Roman history should already know that a combination of genius and popularity always inspired hatred in the Roman elites. Scipio’s public life was therefore brief. An insecure senate accused him of embezzling funds from the treasury. He aptly retorted that his victories had actually filled that same treasury, but only a public demonstration could save him from retribution. Much of the Scipio family’s wealth was confiscated, at which point he voluntarily exiled himself. Supposedly, he wished to be buried in rural Italy away from his family tomb in Rome—the city he once loved, which screwed him over in return.

By all accounts, Crispus was one of history’s most dutiful sons. As the son of Constantine I, emperor of the Western half of the Roman Empire, Crispus served his father’s interests admirably during the early fourth century A.D. Crispus led Roman armies that defeated both Frankish and Germanic invasions. And when Constantine decided he wanted all of the Roman Empire, Crispus commanded the fleet that helped to win the civil war, cementing his father’s position as the sole and undisputed Emperor. Clearly, Crispus was the kind of son that emperors often wish for but never have—talented, humble, and well-liked. All of which makes Crispus’ untimely demise at the hands of his father just that little bit more distressing. We can’t be sure exactly why Constantine did it, since the terrible father struck nearly every reference to Crispus from the public record. But we do know that in A.D. 326 Crispus was executed (or at least exiled—upon which he committed suicide) by order of his father. It’s possible that Crispus was the victim of conspiracy. Constantine’s second wife Fausta wanted Crispus’ dynastic position for her children, and accused Crispus of seducing her. Curiously though, even Fausta wasn’t safe from the emperor: after having his son killed he ordered the execution of his wife by suffocation in an over-heated bath. Given how many horrific methods of execution were used in ancient times, Fausta should probably have considered herself lucky!

Tariq—a former slave—continued the Muslim expansion from North Africa to the Iberian peninsula. Along the way, he lent his name—Jabal-Tariq—to the rocky outcrop of Gibraltar, on the coast of southern Spain where he and his men landed in 711 (about 100 years after Muhammad started his religion of peace). Tariq spent the next year subduing the last pockets of resistance and establishing Muslim rule in what is now Spain. Just one problem: Tariq’s lightning conquest hadn’t been authorized by anyone other than the North African governor Musa Ibn Nusayr. Both Tariq and Musa were recalled to the Umayyad capital, Damascus, to account for their actions. The pair spent a leisurely two years journeying back east, no doubt making the most of the time before their reckoning. Despite the enormous wealth the conquest of Spain brought the empire, both men were accused of insubordination. Musa died in prison, while Tariq Ibn Ziyad, stripped of his rank and position, perished a poor commoner in obscurity.

In the early 1100s, a group of Manchurian peoples called the Jurchens swept down from northern China and violently displaced the Song Dynasty. The Song emperor was captured, and the remainder of the Song court fled southwards. Thankfully, the Song had an officer capable of turning the tide: Yue Fei. Fei did such a good job waging war on the Jurchens and retaking Song lands that it seemed only a matter time before Fei rescued the imprisoned Song emperor. This, of course, did not sit well with the interim Song ruler, Gaozong, who had discovered that acting as emperor was a rather enjoyable affair. Before Fei could retake the former Song holdings in the north, the brilliant officer was recalled to Gaozong’s court. One of Fei’s men was forced to testify against his general, and Fei was imprisoned on charges of plotting a coup. To avoid creating a martyr, the Southern Song court executed Yue Fei in his prison cell and negotiated a peace with their northern Jurchen neighbors. The dead officer’s back bore a tattoo: “repay the nation with utmost loyalty.”

Rogers, an American, founded his colonial Ranger corps in 1755 with the aim of serving alongside the British against the French during the Seven Years’ War. Despite his unit’s success, the irregular and independent nature of Rogers’ Rangers meant that the British felt comfortable paying Rogers—well, irregularly. After the war, Rogers traveled to England where he wrote two books cashing in on his minor celebrity status and the British fascination with the American wilderness. When the American Revolution broke out, Rogers traveled to America and offered his services to George Washington, but was rebuffed and imprisoned as a spy due to the time he had spent in England. Rogers managed to escape, and formed a new ranger corps which fought for the British during the Revolution. Rogers’ best years were behind him, though, and he failed to repeat the success he’d had during the Seven Years War. Rogers fled to England after the Revolution, but mired himself in debt and had to struggle to avoid the poorhouse.

Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, the Comte de Rochambeau, led the French forces that turned the tide of the American Revolution, granting the colonies their freedom from British rule. He didn’t stop there, though. After reluctantly accepting a position as a Marshal of France, Rochambeau fell ill and had to resign. Ironically, the man who had embraced the revolutionary spirit in America came under fire during the French Revolution for his “questionable loyalties.” Despite the fact that Rochambeau was loyal to the ideals and aims of the French Revolution, Robespierre’s Reign of Terror saw fault with the aging retiree, and imprisoned him. Rochambeau—the hero and dutiful public servant—languished in prison for almost an entire year while his fate was being decided. While Rochambeau was in prison, the revolutionary spirit turned on Robespierre, whose execution meant the end of the Terror. During his subsequent trial, the Comte de Rochambeau successfully defended himself, citing his military service with that great symbol of revolutionary spirit and freedom (and full-time slave-owner) George Washington. The invocation of the American Revolution earned Rochambeau his freedom, and the rise of Napoleon allowed Rochambeau to regain some of his former respectability.

The story of the French Revolutionary Army is one of the most incredible triumphs over insurmountable odds in history. Everything from gunpowder to experienced officers (most fled the country) was in short supply following the regicide, and almost every country in Europe had turned against France. Enter the greatest technocrat of all time—Lazarre Carnot. The academic and engineer won an election and took charge of France’s military affairs. Under Carnot: the army’s strength was doubled (to 1.5 million), unseasoned troops were trained into effective soldiers, and most importantly, France won a series of victories that defeated the pan-European alliance. Also, it was Carnot who made Napoleon Bonaparte a general. Carnot served periodically in Napoleon’s government. Carnot’s republican ideals were often at odds with Bonaparte’s imperial aims, yet the Corsican held Carnot in good esteem. No matter his political beliefs, whenever France faced duress and Napoleon called upon the masterful tactician, Carnot answered the call. The whims of a nation are a fickle thing, however. After the restoration of the French monarchy, Carnot’s status as a “regicide” made him a pariah among the people, most of whom had forgotten the barbarous excesses of the Ancien Regime and welcomed the new king. Carnot lived out his resulting exile first in Poland and finally in Germany, where he died in 1816.

Imagine Eisenhower, Patton, and Roosevelt rolled into one man and you’re just beginning to grasp the importance of Zhukov to the Soviet Union and the Allied victory in WWII. At nearly every major battle between Russia and Nazi Germany, Zhukov led the Soviet defense. Zhukov’s Fabian tactics buoyed the Red Army, and bled the Nazi war effort dry. But when WWII ended, Zhukov’s real troubles began. In 1945, Zhukov refused to arrest members of his staff who had looted German valuables. From then on, USSR State Security took a keen interest in him. An increasingly paranoid Stalin—fed rumors by his State Security—decided to dismiss the war hero from his post. After that little piece of ingratitude, Stalin exiled Russia’s greatest general to command the Ural Mountain district—the equivalent to having Patton guard a garbage dump. In Iowa. Zhukov fought his way back to become Minister of Defense in 1955, only to be unjustly implicated in a plot against Premiere Khrushchev. He spent his last years under quasi-house arrest, while Soviet leadership gradually went about wiping Zhukov’s name from Soviet history. Sadly, just as the USSR recognized him again following Khrushchev’s death, Zhukov suffered a stroke. Today Russians—unlike Krushchev—actually celebrate his memory.