Or is it? In the last few years alone, academics, historians, and ordinary Joes have stumbled across enough lost treasures to fill an entire museum.

10Captain Kidd’s Treasure

Former pirate-hunter turned vicious pirate, Captain Kidd’s life story is potential Hollywood gold. It even has one of the most famous MacGuffins of all time: a haul of treasure stolen by Kidd and missing for over three centuries. At least it was . . . until May 2015, when a group of explorers led by Barry Clifford discovered it off the coast of Madagascar. In 1695, Kidd had been put in charge of the Adventure Galley with an express mission to hunt down pirates. When catching professional plunderers turned out to be more difficult than simply becoming one, Kidd allegedly switched sides and loaded his vessel with stolen booty. Kidd’s glorious adventure only lasted three years, when he had to sink Adventure Galley off the coast of Madagascar after it had become unseaworthy. There it lay until 2015, when Clifford and his team finally dived it and found a gigantic haul of silver. At the time of writing, only one bar has been displayed. But boy is it a big one. Roughly the size of an adult’s forearm and engraved with the letters “S” and “T,” it is suspected to have originated in Bolivia. Although it almost certainly belonged to Kidd, experts are urging caution until a closer analysis can be made. If Clifford’s team turns out to be right, their find will go down as one of the biggest of the century.

9Michelangelo’s Only Surviving Bronze Sculptures

As one of the most studied artists in history, finding new work by Michelangelo should be impossible. Or so you would think. In February 2015, academics at Cambridge University revealed that two bronze statues of muscular men riding panthers naked, originally attributed to Michelangelo’s circle, were the work of the master himself. The discovery was the result of detective work worthy of a Dan Brown novel. Last year, a drawing by one of Michelangelo’s apprentices was discovered in France, depicting one of the panther-riding youths. When experts hired an anatomist to inspect further, they found details on the youths’ bodies eerily similar to those on Michelangelo’s David. The six-packs and bellybuttons were identical, and the inclusion of a visible peroneal tendon pointed to a sculptor with a high level of anatomical knowledge. The team then finally made a neutron scan of the bronzes, dating them to the first decade of the 16th century—when Michelangelo was on the cusp of fame. This makes the panther boys the only surviving bronzes by Michelangelo in the known world. If you’re lucky enough to live in Britain, you can even go see them at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

8Charles Darwin’s Lost Fossils

In 2012, paleontologist Dr. Howard Falcon-Lang made the chance discovery of a lifetime. Digging through the vaults of the British Geological Survey HQ, he came across a cabinet drawer marked “unregistered fossils.” Opening it, he found a collection of beautiful glass slides containing cross sections of forgotten fossils. This alone probably would’ve been exciting enough, but then Dr. Falcon-Lang noticed the signature: “C. Darwin, Esq.” Rather than being random old slides, the fossils were the very samples Charles Darwin had picked up on his Beagle voyage while forming the theory of evolution. Back in 1846, they’d wound up in the hands of his friend Joseph Hooker, who was trying to build a collection. Unfortunately for posterity, Hooker failed to register the slides and then vanished off on an expedition to the Himalayas without telling anyone about them. The collection was packed up while he was away and moved to a new location. In the confusion, everyone forgot all about the invaluable Darwin samples for 165 years.

7Walt Disney’s First Christmas Movie

In 1931, Disney released Mickey’s Orphans, a Christmas-based tale starring a certain iconic mouse that is now considered an early classic. Not many know that it was based on an even earlier film. Empty Socks was released in 1927 and was long considered lost. So culturally important was this missing film that the few surviving frames were preserved in the Museum of Modern Art in New York. That all changed in 2014, when archivists at the National Library of Norway unexpectedly stumbled across a copy. Running across two reels for a total of five and a half minutes, the Norwegian version of Empty Socks was only 30–60 seconds short of being complete. At some point, someone working at the library had messed up labeling it, and its existence was forgotten. Its recovery was fantastic news for film historians and Disney fans. Empty Socks featured Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, who would go on to inspire the most famous Disney creation of all: Mickey Mouse. Seeing him in a story that would later be remade with Mickey allowed experts to see clearly how Walt Disney’s ideas evolved over the early years. There’s no word yet as to when someone will finally put a version on YouTube.

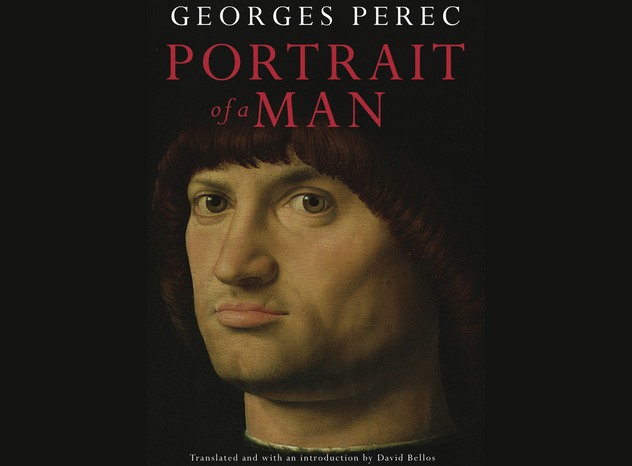

6Georges Perec’s Lost Novel

For decades, fans of the French avant-garde novelist Georges Perec had been tormented by a throwaway reference in his semi-autobiographical novel, W. In one tantalizing passage, Perec briefly described his first unpublished book, Portrait of a Man. Yet when Perec died, no copy of the manuscript was found. As the author of one of the great novels of the 20th century, Life a User’s Manual, a new book by Perec would’ve been an invaluable cultural treasure. Its absence sparked a search through his papers that turned up nothing but blanks for over 30 years. Then one day, a former journalist just happened to mention to a Perec expert over dinner that a friend had once lent him some of Perec’s writing. He offered to show it to the expert and promptly handed him the sole surviving copy of Portrait of a Man. It was the literary equivalent of an acquaintance casually tossing a first draft of the Mona Lisa into your lap. By 2014, Portrait of a Man had been copied, translated, and finally published—nearly 40 years after readers first heard of its existence.

5Vivaldi’s Lost Opera

Although he’s most famous for The Four Seasons, pretty much everything to come from Vivaldi’s pen was unqualified genius. His opera Orlando Furioso is no exception. A masterpiece composed in 1727, it’s the sort of work that drives opera lovers into a dignified frenzy with its raw power. Yet the version most people know is actually a remake. In 2012, researchers discovered a version in Vivaldi’s papers dating from 13 years earlier. It was long known that an Orlando opera had been staged at Vivaldi’s theater in 1714 and had been a massive hit. It was also known that Vivaldi kept a copy of this opera in his personal papers. But somehow, no one had put two and two together, and it was instead cataloged as the work of the Bolognese composer Giovanni Alberto Ristori. It was only when a leading scholar decided to investigate why Vivaldi kept a copy of Ristori’s work that it was discovered he didn’t—the opera was Vivaldi’s all along. The new version of Orlando has since been performed and recorded. You can hear a sample of it in the above video.

4Britain’s ‘Most Wanted’ Missing Film

One of the most terrifying statistics ever released is the claim by the Library of Congress that 75 percent of all silent films are lost forever. In Britain, that number rises to 80 percent. Even bona fide geniuses like Hitchcock have films missing. So when experts stumbled across one of the most sought-after British films in a Dutch blacksmith’s garage, it felt like the haul of the century. Directed by George Pearson, Love, Life and Laughter had been at the top of the British Film Institute’s “most wanted” list for years. Directed in 1923, it starred Britain’s “Queen of Happiness” Betty Balfour in a role critics claimed would be remembered for centuries. Instead, the film’s surviving print wound up gathering dust in a small-town theater in Holland, before being given to a local blacksmith when the theater closed. It then moldered in his garage for decades, until his relatives bequeathed it to the Dutch Film Museum EYE, who told them exactly what they’d been sitting on all this time. The film is extra important because it doubles the amount of existing films directed by Pearson, a man known as “Britain’s D. W. Griffith.” With two surviving films, we can now finally see if he was really any good or not.

3Neil Armstrong’s Haul Of Apollo 11 Artifacts

The footage of Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the Moon may be the most iconic piece of film in history. Yet, for decades and decades, we were unaware that we had an artifact connected with it here on Earth. Then, two years after Armstrong died, his wife discovered an old bag hidden at the bottom of a closet. Inside was the camera the Apollo 11 crew had used to record mankind’s first footsteps on the Moon. Aside from being a physical reminder of our species’ greatest collective achievement to date, the find was awesome because the camera was meant to be lost forever. After the mission was over, the camera and other bits and pieces in the bag were supposed to have been left in the Eagle module. The Eagle never made it back to Earth. By rights, that camera should’ve been lying in a pile of wreckage, somewhere on the surface of the Moon. It turned out that Armstrong had deliberately smuggled it back to Earth disguised as “10 pounds of LM miscellaneous equipment.” He’d told Michael Collins the bag contained nothing but trash, and apparently NASA believed him. Armstrong never once spoke about the priceless memento he was hiding in his closet. The camera is now on display at the National Air and Space Museum.

2A Lost Leonardo Painting

Despite being possibly the greatest artist to have ever lived, the number of surviving works we have by da Vinci is absurdly small. Depending on who’s counting, we have somewhere between 15–17 of his paintings. By comparison, we have dozens by Michelangelo and even more by Raphael. In 2011, this tiny total got a significant boost. After years of analysis, experts declared Leonardo had painted the Salvator Mundi. A picture of Christ holding a glass orb in one hand, the Salvator Mundi was long considered one of Leonardo’s many lost works. It was described in a collection of 17th-century documents, but after that it simply seemed to fall off the face of the Earth. Unlike the Battle of Anghiari or the Mona Vanna (a nude Mona Lisa)—which we knew had been destroyed—Salvator Mundi‘s disappearance was always considered a mystery. Then, a few years ago, a consortium of businessmen bought a murky painting of Christ long considered to be a Salvator Mundi knockoff. After paying to have it cleaned and restored, they discovered the glass orb in Christ’s hand was painted really, really well. In fact, it showed such great technical skill that scholars declared it could only have been done by da Vinci. The attribution handed the world another painting by the Renaissance master. Unfortunately, it’s currently held by a Russian billionaire, so good luck ever seeing it in the flesh.

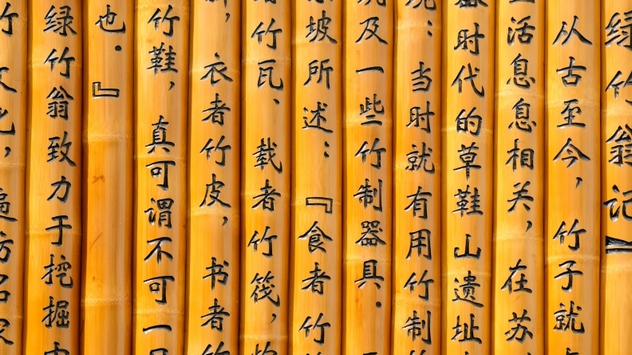

1The Lost Writings Of Chinese History

Every so often in human history, something is rediscovered that could potentially change the world. One example is when scholars rediscovered the works of the Greeks and Romans, ushering in the Renaissance. Another could be the discovery of the Tsinghua Bamboo Slips. A collection of ancient bamboo pieces covered in Chinese characters, the slips contain some of the earliest Chinese writings ever uncovered. Along with two similar hauls dating back to 1993, they seem to represent a school of Eastern literature and science completely forgotten by the world. Perhaps most importantly, they predate the first Qin emperor by nearly a century. In 213 BC, the emperor ordered all books to be burned and scholars to be murdered. The result was a grand loss of knowledge and culture, as thousands of irreplaceable texts went up in smoke. Fast-forward to today, and we may be finally getting some of them back. Already, analysis of the three manuscript hauls has revealed the earliest known version of the I Ching, new texts by Confucius, and a prototype version of the Taoist Book of the Way, with major differences from later editions. It’s also uncovered the oldest use of a decimal multiplication table in history. With its many treasures only now starting to make their way into public consciousness, it’s even been suggested we may soon see a wholesale rewriting of Chinese cultural history. Not bad for a bunch of moldy, old bamboo strips.