Ancient Roman cuisine is no different. Some things, like bread, wine, and olives, are widely used in modern Western cuisine today, while others, like their strong fish- and grape-based sauces and savory souffles, wouldn’t be on the menus of even the most experimental gourmet restaurants. In this list, we’re shedding some light on the dining habits of ancient Rome.

10 The Mediterranean Triad

At its heart, ancient Roman food was built on three ingredients: grapes, grains, and olives. Scholars call these the “Mediterranean Triad.”[1] Grapes were eaten as they were, but they could also be made into wine of different qualities, from the vintage wines preserved for the elite down to the cheapest acetum, or vinegar, which was used in cooking but also for a wide variety of other purposes, such as extinguishing fires. Grain was the dietary staple of everyone from richest to poorest. In wealthy households, wheat would be finely ground and baked into doughy white bread or made into fancy porridge with a variety of other ingredients. The very poorest of Rome were entitled to a free grain dole, which they would either take to a baker who would make it into bread or make porridge with it themselves in a pot of water. Olives were essential for daily life—as a food, of course, but mainly as olive oil, which was used for everything from fueling lamps to washing after exercise. Without these three ingredients, Roman cuisine couldn’t have existed.

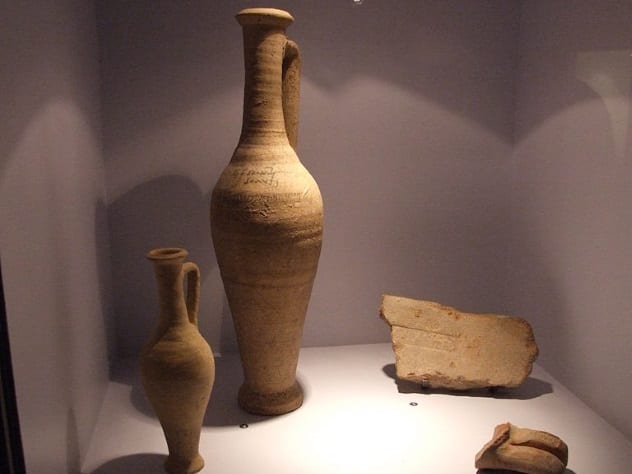

9 Garum

At the height of its use in the first century AD, garum was incredibly popular. It was frequently combined with wine, oil, ground pepper, and even just water to make a range of different sauces or drinks that could be consumed straight or added to other meals. Even the most cash-strapped laborer could afford basic garum, while the most advanced garum would bankrupt even the wealthy middle-class landowner. Factories dedicated to its production sprang up across the empire, and dedicated trade routes carried garum to its furthest reaches. But what was garum? Fish sauce.[2] There is no direct equivalent in the West today, though the fish sauces of Asia come close. Wildly popular at its height, it faded with the fall of the Romans and drifted out of Western cuisine. Even the simplest garum took a long time to make, though it wasn’t very labor-intensive. Essentially, garum was made by layering the innards of gutted fish between salt and aromatic herbs and spices. Left in the sun for months, the fish innards would ferment into a very pungent paste. The amount of salt was important: Too little salt, and the fish would putrefy; too much, and the fermentation process would be disrupted. The mixture would then be strained to produce the amber sauce that graced Roman dinner tables from the Middle East to Hadrian’s Wall. When the straining process was over, the paste that was left over was also sold as a food additive, though it wasn’t nearly as valuable. Because garum was basically made from salt and the leftovers of the fishing industry, simple garum could be very cheap. The best garum, however, was made from particular types of fish and with particular combinations of herbs and spices, the recipes of which were closely guarded secrets. According to Pliny the Elder, the best garum was made on the outskirts of modern-day Cartagena, Southern Spain, and it was called garum sociorum.

8 Puls

Grain was the staple of the Roman diet, and the easiest food to make from grain was puls, or porridge. At its most basic, porridge was simply grain boiled in water until the water reduced and the grain softened.[3] Salt was then added if it was available—unlike modern porridges, Roman porridge was nearly always a savory dish. More luxurious porridge, sometimes known as Punic porridge, would contain things like honey, cheese, and eggs and could form the basis of a nice, hearty meal. The very best porridge even had the luxury of added herbs and spices. In the Roman army, food was prepared at the contubernium level—the unit of eight men who marched, ate, and slept together. The responsibility for cooking meals often fell to one or two men in the unit. And since the grain ration was distributed raw, soldiers usually made their ration into porridge, since it was hard to find time in the busy schedule of a Roman soldier to make bread. Because of this, porridge was stereotyped as the food of the poor and the army, so the richer class of Romans avoided it wherever they could.

7 Panis Quadratus

If porridge was the easiest Roman food to make, bread was the most common—especially in the later years of the empire, when the free grain dole for the poor was replaced by free bread. Bread was produced on an industrial scale in large bakeries, and the standard form was the panis quadratus, a circular loaf scored along the top to form eight slices.[4] Archaeological explorations in the Roman city of Pompeii have turned up carbonized examples of panis quadratus as well as many wall frescoes featuring it in bakeries. Judging by the archaeological record, panis quadratus was a commonly eaten food item, at least in urban environments, where many people would have been buying their food rather than growing and cooking it themselves. As for the recipe, it was not too far removed from how bread was prepared up until the modern era: The cheapest breads would have been very dark, while the most expensive would have been lighter, having been made from finer flour. Because flour was ground in a stone mill or quern, bits of stone would have entered the mix and worn down people’s teeth over time. As always, people had to be on the lookout for low-quality bread made from bad flour. In an effort to tackle this, bakers were required to stamp their bread with their own personal identifier so that they could be tracked down by the authorities if they tried to cheat a customer.

6 Posca

Winemaking was a giant industry in ancient Rome, and like all industries, it produced waste. In this case, the main waste product was wine that went bad or didn’t age properly, becoming vinegar or acetum. The Romans were good at repurposing their waste, though, and this vinegar was put to many uses. It was primarily used to make posca, a drink favored by the lower classes and the military for its availability and cheap price.[5] In military circles, it became such a standard drink that imbibing normal wine was looked down on or, in the case of armies in the field, banned entirely. Drinking vinegar may sound disgusting, but it can be made quite palatable by adding a few ingredients. The cheapest posca seems to have been a mix of vinegar-wine and water, which must have been an acquired taste at best but was safer than drinking straight water. Higher-quality posca was made by adding honey and spices such as coriander, which would disguise the bitter, acidic taste of the acetum.

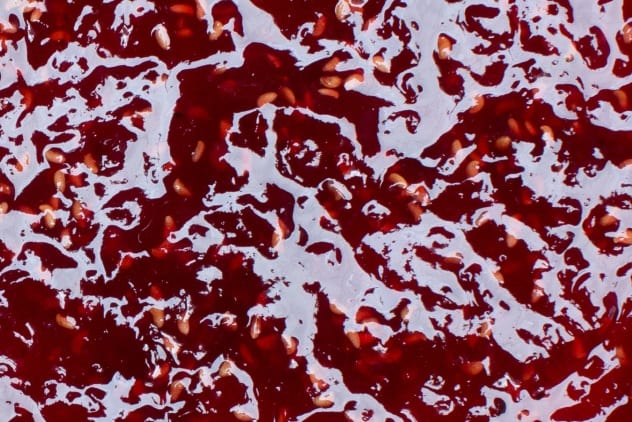

5 Defrutum

Alongside the spoiled wines and vinegar that the Roman wine industry inevitably produced, there were also the leftover grape skins, pits, and pulse that didn’t end up in the final product. Never being ones to waste potentially useful materials, the Romans used these leftovers to make a cheap sweetener called defrutum (sometimes spelled defritum).[6] There is some debate over the difference between defrutum and sapa, which were both made with grape must. Since the writer Columella seems to use the words interchangeably, it’s possible they were the same thing. Defrutum was basically a cheap material that could be added to meals to bulk them out, giving them flavor and calories. It seems to have been quite similar to a modern-day jam or preserve: Ancient recipes describe adding the mix to a pan and cooking it until it turns thick and reduces by either a half or a third. Honey was a better sweetener, but it was also more expensive and only produced in certain regions, while wine was made in nearly all corners of the Roman empire. And while it may not have been the most desirable foodstuff, porridge with grape jam would have been much more enjoyable than plain porridge.

4 Silphium

In the old region surrounding Cyrene, a plant grew in Roman times that was always in very high demand. This plant, which was called silphium, was sought after because it was highly flexible. It was tasty whether roasted, boiled, or eaten raw.[7] Its sap, when dried and grated, was a great addition to most meals, and it was also used to make perfume. It played a central role in many herbal medical treatments, especially for “growths of the anus” and treating dog bites. Finally, and perhaps most incredibly, it also seems to have been taken to “purge the uterus,” or as an early form of contraceptive. It became a key part of Roman and Greek culture, referenced in poetry and literature. It even appeared on the backs of some Greek coins. Cyrene, for its part, became incredibly rich off the back of the silphium trade. Julius Caesar also recognized its value, keeping 680 kilograms (1,500 lb) of it in the national treasury. However, the plant would only grow in the region immediately around Cyrene, and the many attempts to cultivate it all failed—even those led by the Greek botanist Theophrastus. It had to be gathered in the wild. In later periods, the kings of Cyrene tried to protect it by fencing it off, but they were unsuccessful. By the mid-first century AD, it had all but disappeared. The last recorded specimen, appearing sometime between AD 54 and 68, was presented to Emperor Nero as a curiosity.

3 Moretum

So, the diet of an average Roman soldier or laborer was bread, porridge, and vinegar-water. Not much to get excited about. However, the poet Virgil writes about a peasant plowman preparing his breakfast in one of his poems. He makes himself some moretum, or cheese salad, which he eats with a flatbread.[8] Roman cuisine was very bold in its flavors, and though the poorest would have lived off a simple diet, even the cheapest sauces—like the one in this poem—were still packed with taste. The farmer’s cheese salad was basically a garlic sauce. It was made with aged sheep’s or goat’s cheese, parsley, rue, dill, coriander, salt and vinegar, olive oil, and four whole bulbs of garlic, all crushed into a paste with a mortar and pestle. The paste was then spread over a flatbread, which often doubled as a plate in the Roman world—one which you could eat. This kind of meal was quite common, and we find mortars and pestles scattered all across the Roman world. Though the coriander would have been expensive, the rest of the ingredients wouldn’t have been too hard to come by. Most rural peasants had their own herb garden, so the plowman would have gotten his parsley, dill, and garlic for nothing at all, and bread, salt, vinegar, and olive oil were, as we’ve already learned, the most common foodstuffs in the Roman world. Even though the richest and most elaborate foods were reserved for the elite, even a rural peasant could enjoy a relatively tasty breakfast at minimum cost.

2 Patina

A patina was a Roman dish similar to a modern-day souffle. It could be sweet or savory, a dessert or a main meal, depending on what was cooked into it. The patina was very popular, at least among the Roman elite: In Apicius’s recipe book De Re Coquinaria, there are 36 different recipes for patinae, containing ingredients from pears to fish. Since Roman cuisine loved to combine sweet and savory foods in the same dish, many of these recipes seem strange to our modern palate—but eggs were perfect for Roman cooking, since they can be both sweet or savory depending on what ingredients they are put with. Eggs were the main ingredient in a patina, which were combined with the other components in a special kind of pot that was usually placed directly into the embers of a fire. If the patina was cooked with the lid on, it would turn out lighter and more fluffy, but if the lid was kept off, it would be heavier and crispier. As such, it was a very versatile food that could take many forms. One of the recipes, for a “Patina of Pears” (result pictured above), calls for the use of nine ripe pears, sweet wine, honey, olive oil, cracked peppers, six eggs, cumin, and fish sauce. These would be mixed together into a paste and cooked in the pot for about an hour until it hardened.[9]

1 Gustum De Praecoquis

One of the best examples of the Roman taste for dishes that were sweet and savory at the same time also comes from De Re Coquinaria. Gustum de praecoquis was a starter dish that would only have been served in elite Roman households, since the lower classes almost never ate multicourse meals. Such a dish would be used to impress guests with both the ingredients the host had access to and the skills of the cooks they could afford to employ. Gustum de praecoquis was, simply, apricots in sauce.[10] The cook would boil some apricots in a pan. Then they would add ground pepper and mint, fish sauce, raisin wine, wine, and vinegar, along with a small bit of olive oil. Once the liquid reduced to a sauce (and the apricots were very soft, if not dissolved into the sauce), the cook would sprinkle it with more pepper and serve it. This dish was undoubtedly sweet and could easily have been served as a dessert rather than a starter. But the addition of pepper, vinegar, and fish sauce would have given it a sharp, almost bitter tang.