Pioneer children, in the days of the American frontier, would often be kidnapped by raiding warriors. When Native American tribes lost their own children in wars with the settlers, they would even the score. They would raid a white village, take their children, and carry them back to their homes as hostages. But when their families tracked them down and tried to rescue them, sometimes, the children didn’t want to go home. It was a strange phenomenon the settlers of America struggled to understand. Even Benjamin Franklin commented on it. “They become disgusted with our manner of life,” he once wrote about the white children captured by native tribes, “and take the first good opportunity of escaping again into the woods, from whence there is no reclaiming them.”[1]

10 Frances Slocum

In 1835, a trader named George Ewing met an elderly woman of the Miami tribe named Maconaquah. She was in her sixties and a respected woman among the tribe, a widowed grandmother whose husband had been their chief. And so you can imagine his surprise when this old woman told him she had born to white parents. As a child, he soon found out, Maconaquah’s name had been Frances Slocum, the daughter of a Quaker family who had been stolen away from home by Seneca warriors when she was five years old. A Miami family had bought her for a few pelts, and they’d raised her as their own. 57 years had passed since her capture. She’d grown up among the Miami, gotten married, seen her husband rise to chiefdom, given him four children, and raised them until they had children of their own. Frances’s brothers hadn’t stopped looking for her since the day she was captured. When word got out that she was still alive, her brother Isaac met with the sister he’d lost decades ago and begged her to come home. Frances, though, had forgotten how to speak English. Communicating through an interpreter, she told him, “I do not wish to live any better, or anywhere else, and I think the Great Spirit has permitted me to live so long because I have always lived with the Indians.”[2] True to her word, she stayed with her captors until the day she died—and she was buried next to the man who had been her husband.

9 Cynthia Ann Parker

Cynthia Ann Parker was nine years old when she was kidnapped by Comanche Indians in 1836.[3] Her family was slaughtered, and she and four other children were dragged off into the night. Incredibly, she survived the whole horrific ordeal—but she wouldn’t survive going back home. Four years after her capture, a trader named Williams heard that she was still alive, living among the Comanche. He rode into their camp and offered their chief any amount of money he wanted for her freedom. But when he was given the chance to speak to her, Parker simply stared at the ground and refused to say a word. It took another 20 years before she was freed. A Texas Ranger force attacked the Comanche tribe, and upon seeing the white-skinned Parker among them, brought her back to her family. After 24 years living among the Comanche, though, Parker wasn’t happy about going home. She had been there so long that she’d married one of the Comanche warriors, a man named Peta Nocona, who the Rangers had killed. As far as she was concerned, these men weren’t her liberators. They were murderers who had killed the man she loved. They brought her to her uncle’s farm, but Parker didn’t want to be there. She repeatedly tried to run away, and when she realized she wouldn’t escape, she simply stopped eating. Rather than live among the white man, Cynthia Ann Parker starved herself until, weakened and plagued by influenza, she died.

8 Eunice Williams

Eunice Williams’s father got to see her change. After she was kidnapped by Mohawk warriors (reenactment pictured above), her father, Reverend John Williams, tracked her down and tried to get them to let him buy her freedom. The Mohawks refused to sell her, but they did let Rev. Williams talk to the daughter who would never be his again. Young Eunice was terrified by everything around her. She told her father about the rituals the Mohawks performed, telling him they were “mocking the Devil.”[4] She’d described a French Catholic missionary who’d been making her pray with him. “I don’t understand one word of [the prayers],” she told her father. “I hope it won’t do me any harm.” Ten years later, a man named John Schuyler went to see Eunice—but now she was a completely different woman. She dressed and lived like a Mohawk. She had converted to Catholicism, married a warrior, and refused to speak English. He only got four words out of her the whole two hours he spoke to her. When he asked her to come home and see her father, Eunice simply said: “It may not be.”

7 Mary Jemison

Mary Jemison went through one of the most brutal kidnappings of any child. The story of how her Iroquois kidnappers massacred her family is absolutely horrifying—and yet, for some reason, she willingly stayed with her captors until the day she died. Mary was 13 years old when a raiding party from the Iroquois Confederacy attacked her home. The Jemisons were forced to march through the woods, urged on by a warrior with a whip who lashed them whenever they slowed their step. They were not fed. If someone asked for water, the Iroquois warriors would force them to drink urine. In the morning, Mary was pulled apart from her family and forced to march another day. She spent the day wondering what had become of her parents. Then, when nightfall came and they stopped to rest, she found out. While she watched, a warrior pulled her mother and father’s severed scalps out of a bag, scraped them clean, and dried them over a fire.[5] She remembered seeing her parents’ scalps dry for the rest of her life. In her old age, she would relate the story as if it was a swashbuckling adventure from an exciting childhood, but she never left her home. She moved in with a Seneca family, married a Delaware man, and, for reasons only Mary Jemison truly understood, became so attached to her family that she refused to ever leave their side, regardless of what had happened to her parents.

6 Herman Lehmann

Herman Lehmann didn’t see himself as a white boy living among the Apaches. To him, he was an Apache warrior through and through. He was kidnapped at age ten, and it changed him so much that when he was found eight years later, he couldn’t even remember his own name. By then, Lehman was a respected warrior in his tribe who called himself “En Da.”[6] He’d been made a petty chief for his ability to fight, and he’d joined the Apaches in raids and battles, even leading a charge right into a fort full of Texas Rangers. All that changed, though, when a medicine man killed his adoptive father, an Apache warrior named Carnoviste. Lehman took his revenge and killed the medicine man. He then had to flee into the wilderness. For a year, he lived alone, hiding from the Apaches and the white men alike, until he finally settled down in a Native American reservation. When his mother heard there was a white-skinned, blue-eyed boy on the reservation, she came out, praying it was her son. At first, she didn’t recognize him, and Herman was less than friendly. “I was an Indian,” he explained, “and I did not like them because they were palefaces.” But Herman’s sister spotted an old scar only he could have and, overcome with joy, cried out, “It’s Herman!” The sound of the name puzzled him. Somehow, Herman thought he’d heard it before. It took a long moment, Herman would later recall, before he realized that he was hearing his own name.

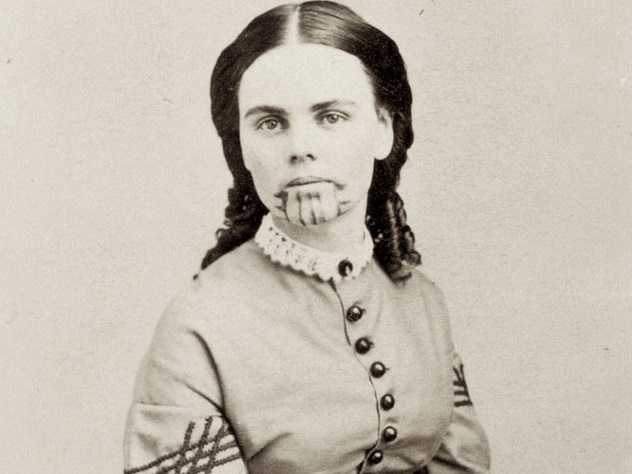

5 Olive Oatman

When Olive Oatman wrote about her life as a Mohave captive, she called them “savages.” She wrote about them as if they were wild men and her time with them had been hell, but there were hints she wasn’t telling the truth. The biggest clue was as a plain as her face: the large, blue tattoo that covered her jaw. Oatman had grown up in a Mormon family, but she was captured by Apaches while her family was traveling to California. The Apaches had sold her to a Mohave family that took her as her own, and for five years, she lived as a Mohave. When Olive’s brother—the sole surviving member of her family—found her, her tribe was suffering through a famine, and many were starving. The people around her were dying, and, worried for her life, her adoptive family let her go home. Oatman wrote a book about her experiences that criticized the Mohave, but there were signs she wasn’t being totally honest. She dressed like them, lived like them, and had willingly agreed to the blue tattoo on her face. And she’d claimed that the “savages” had not made her “unchaste”—but her name among the Mohave was “Spantsa,” a name meaning “sore vagina.”[7] Nobody knew the truth about Olive Oatman’s experience except for her. But some believe that living among the Mohave may have changed her more than she was willing to admit.

4 The Boyd Children

The five Boyd children managed to get away from their captors. After years living with Iroquois and Delaware families, their father brought them back home. Instead of being grateful, though, they bolted into the night. They fled their father’s home to get back to the people who had kidnapped them. The children had been taken by Iroquois raiders and dragged out so they could be sold to other tribes. On their painful road into captivity, they were forced to watch as the warriors beat their pregnant mother to death for failing to keep up the pace. Her dead body was left behind. It took four years before their father, John Boyd, was able to rescue any of them. The first one he saved was his eldest son, David. The boy wasn’t as happy to see his father again as John had hoped. David protested and said he didn’t want to leave his Delaware family and, after a short time, snuck out in the night, left his father’s farm, and went back to the tribe.[8] Over the next four years, his father went from tribe to tribe, buying his children’s freedom and bringing them back home—and saw nearly every single one sneak out into the night and leave him to go back to their captors. He freed every single one of his children, but he wasn’t able to keep them all at home.

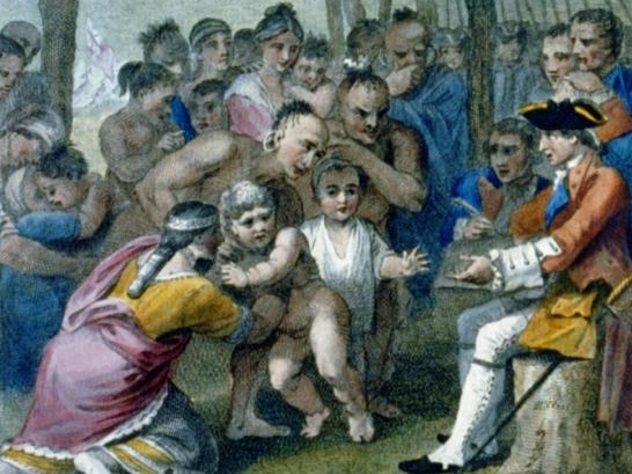

3 Mary Campbell

Mary Campbell is just one name among hundreds of children who were kidnapped during Pontiac’s War. She, and the other children like her, were stolen away from their parents’ homes and sent to live with native tribes as revenge for the deaths of their own people, meant to replace the children the native tribes had lost. When the war ended, Colonel Henry Bouquet demanded the children be released. He drew up a list of over 200 names of children who had been abducted from their homes, handed it to Pontiac’s warriors, and made them promise to return every one if they ever wanted to see peace in their lives again. The tribes agreed, and the 200-plus children were sent back to their families. Mary Campbell, though, had to be dragged back to her family by force. She didn’t want to go home—and even once they brought her back, she still tried to escape and run back to the Lenape family that had captured her. It’s a strange story, but Campbell wasn’t the only one who tried to run from her parents. Of the children Col. Bouquet freed, nearly half tried to escape their biological families, preferring to live with the families that had kidnapped them rather than the ones that had brought them into the world.[9]

2 Theodore Babb

Theodor Babb, 14 years old, was determined to hate his Comanche captors. They had murdered his mother and dragged him and his ten-year-old sister Bianca into captivity. They could kill him if they wanted, Theodor decided, but he would not live among them. After days of being beaten for his stubbornness, Theodor tried to escape from his captors, but he didn’t get far. The Comanche dragged him back and beat him brutally. Theodore, though, wouldn’t give them the satisfaction of crying. He wouldn’t even flinch, no matter how hard they hit him. Frustrated, the Comanche tied him to a tree and started placing grass and branches at his feet, ready to burn him alive. Bianca wailed and cried for her brother’s life, but Theodor still wouldn’t flinch. Throughout it all, he stared the men who were getting ready to kill him in the eyes, daring them to go through with it.[10] They didn’t. The Comanche realized this young boy was unusually brave and, instead of killing him, trained him to be a warrior. They armed him, taught him to ride like a Comanche warrior, and showed him how to run raids. For all he’d resisted it, as a Comanche warrior, Theodore started tapping into a part of himself he’d never been able to touch before. Within six months, he was so much a part of the tribe that when his father tried to buy him back, the Comanche chief was convinced he would refuse to leave. In the end, Theodore did go home—but he had changed. After just six short months of captivity, he was already a Comanche warrior who had joined in on multiple raids on white men’s farms.

1 Adolph Korn

After Adolph Korn was freed from his Comanche captors, his parents moved him far away from the tribe that had harassed them. Unlike the other children on this list, he had no way to get back to the people who had kidnapped him, so, rather than live with his own parents, he fled into the wilderness and spent his life alone in a cave. Korn had been captured when was ten years old and sold to a childless Comanche woman. She took him in as his own, and although he was initially distraught over losing his family, he soon started to enjoy it. Living in a frontier home, he’d struggled to get any attention from his eternally busy parents. Now, though, he had an adoptive mother who focused every second of her energy on him. He felt more loved that he had ever felt before. His parents managed to get him home three years later, but he never stopped being a Comanche. He would raid his neighbors’ farms and steal their cattle. Soon, he’d built up a long police record, and terrified they’d lose their boy to a different type of captivity, his parents moved far away to a remote ranch. Korn, though, refused to become a white man. Instead, he left his parents’ home and moved into a cave, where he lived in solitude until the day he died. As a family member said, for the rest of his life, “Adolph kept a solitary vigil for the Comanche brothers whom he knew would never return.”[11] Read More: Wordpress