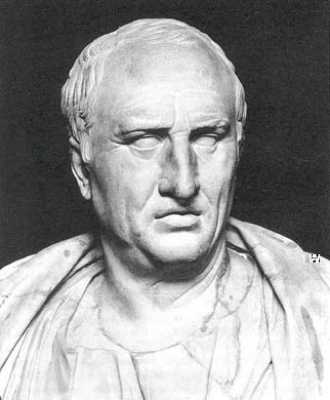

Miserliness is defined as extreme frugality with money. The miser may spend very little on himself but a lot on others, or a lot on himself and very little on others, or, typically, very little at all. Cato of Utica was known for being fiercely moral in a time when it seemed no one in Rome gave even the slightest passing nod to morality. 99% of the politicians were so corrupt that there was no real point in voting for any of them. They promised a better life, but when they were elected, they ignored the people. Cato was not those men. He campaigned for various political offices, winning some, losing others. His losses were not due to his extremely conservative politics, but because he refused to give or accept bribes or extort voters, which almost every other politician was doing all the time. Meanwhile, Cato garnered for himself a firm following among the public, more out of awe and disbelief at his impossibly high moral standard than his political brilliance. He denied himself as many comforts as he could. His personal wealth is estimated to have been in the millions, and yet he lived in the most meager, sometimes squalid, rooms of the house he inherited from his uncle. When he moved out to pursue higher education and a career, he bought the cheapest house he could find. He drank only the cheapest wine he could buy in Italy, frequently traveling by carriage into the Appennine Mountains to buy it cheaper. He usually drank water from the Tiber or milk, and only begrudged himself wine because it was healthy. He ate only until he did not feel hungry, and exercised as if he were tempering himself like steel: running as fast as he could until he collapsed and blacked out from exhaustion, waking up in frigid rain, taking off all his clothes and running as fast as he could back home. Anyone attempting to borrow from him was given money once. If they failed for any reason to return it, regardless of whether he could spare it in the first place, he never loaned them money again. Plutarch states that the only time Cato spent lavishly for any reason was to pay for his brother’s magnificent funeral.

Nollekens was a British sculptor, perhaps the finest of the 18th century. The best source of information on him is in a biography his executor published, in 1828. This lister was not able to get his hands on a copy, and so this entry is rather sparse, but from the few snippets he was able to glean from elsewhere, Nollekens was a miser of the first order. By the time of his death, as the most popular, sought-after scepter in England, he left an estate, including a beautiful country manor, worth 200,000 pounds sterling. Today, that would make him a multi-millionaire. Not exactly a starving artist, but then he was by his own volition, because he ate the cheapest foods he could find, and still haggled the grocers over single schillings. When asked his favorite food, he said, “Whatever is cheapest.” When asked his favorite wine, he replied, “Water from the Thames.”

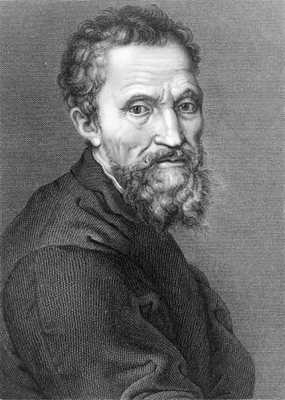

We know him as a Renaissance Man, history’s greatest sculptor, one of the greatest painters and architects, and yet, while he became very wealthy from his many pursuits, Michelangelo actively enjoyed depriving himself of any comfort he saw no need for. He told his workshop assistants and friends that he didn’t care what food tasted like. He knew of no food that was not palatable, and only ate what was cheapest in providing him a balanced diet. He preferred to drink water, but understood the health benefits of wine, drinking only the cheapest he could find. His house was modest and abjectly squalid, infested with rats, and partially dilapidated, but in the coldest weather, he would not patch the holes in the walls, but simply put on another coat, or even go outside and jog for a while. He once stated that because he had never been bitten by a flea, the rats did not seem a nuisance to him. He wore the same, old dirty clothes, day after day, washing them and himself about twice a month in the nearest river or lake, even though the public bathhouses charged about 5 cents to enter. He wore a pair of shoes until the soles nearly came off, mindless of his exposed toes.

Pereira was born in Vienna in 1739, into a barony of the Holy Roman Empire, and thus never once wanted for money. He took his father’s title and married the daughter of another rich nobleman, increasing his fortune to a total of about 200,000 pounds sterling by his death. He outlived his wife and left his estate to his two daughters. He had never entrusted the money to a bank of any kind, instead hiding it in various small caches throughout the tiny shack he moved into to conserve his wealth. His miserliness stems from losing a 15,000-acre plantation in America, when the American Revolution broke out. After this, he became extremely abstemious in all daily affairs, drinking only water, and sometimes eating only stale bread for months. He sold all his opulent estates and moved into that tiny shack to further increase his income. The shack was nicknamed “Starvation Farm,” because he loathed feeding his cattle. He sold all his sheep once he discovered that sheep will eat grass all the way to the dirt, then dig up the roots and eat them, leaving no fodder at all. He then kept only pigs, cows, horses and a few kinds of bird. His second wife divorced him when he refused to give her any gifts or fine cuisine, which he could easily afford. He was elected to the post of Warden of his local Portuguese synagogue in 1765, but had never wanted the post and refused to serve, until threatened with a very small fine. He preferred to serve as warden rather than pay it.

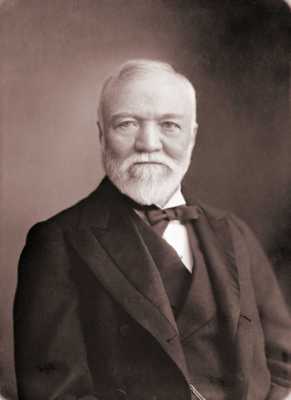

Carnegie is the closest person on this list to Charles Dickens’s ideal of Ebenezer Scrooge, the changed man. Today, Carnegie would be worth around $300 billion. Bill Gates wishes. Carnegie remains, possibly, the second richest person who ever lived, factoring in inflation, surpassed only by John Davison Rockefeller. He made his fortune in the US Steel Industry, which was the first corporation in world history to achieve a market capitalization over $1 billion. But while he was in charge of it and making the most money off it – sums beyond imagination – he deprived himself and most everyone around him of any of it. He stored most of his wealth in 50-year gold bonds, which do not depreciate, and he housed them in a special vault just for him, in a bank in Hoboken, New Jersey. He often went there, sat in the vault and admired the view. Meanwhile, he preferred to eat only when he was very hungry, and attended to his business in earnest in order to ignore any hunger pangs he felt. When he did eat, of course, he ate a lot. He liked to go hunting, and stated once that if he missed any game animal with his first shot, he refused to take another for two reasons, first, that he shouldn’t have missed, and second, that ammunition was expensive. Nevertheless, late in life, having always touted the degradation money brings to everyone who has a lot of it, he devoted his life to philanthropy, giving with extreme generosity to a variety of causes. He also wrote a famous newspaper article, “The Gospel of Wealth,” in which he preached that the rich should give all but what they absolutely need to the poor and needy.

If you’ve heard of him, you impress this lister, who tracked down a newspaper clipping of him on the Internet. He died in 1891, at the age of 56, despite being worth an inherited $9,000, which today would be worth about $215,561.23, according to an inflation calculator. Yet he lived for the last 25 years of his life in a tiny, unheated apartment at 329 E. 10th Street, on Manhattan Island, NYC. The only thing he was ever seen to spend money on was food, and that he bought from the cheapest vendors on the nearest street corner. Then he would run back inside, up the stairs to his bedroom, close and lock the door. If anyone wanted to see him, they would beat on his front door until he answered them through his closed bedroom window. The night before he died, he did not call a doctor. He called a lawyer, whom he ordered to draft his last will and testament. He left all his money to the wife of his apartment building’s janitor, without giving a reason. He had somehow managed to starve himself over the outrageous price of food (in 1891, you could buy half a roasted chicken, potatoes, beans, bread, butter and jam, milk, coffee, and an entire quart of lager beer for a total of $1.50), and died of malnutrition, exacerbated by a perforated ulcer, which is quite painful. The doctor who examined him knew of his medical problem (and why he suffered from it) and estimated at Steubendorf’s death that, had he eaten one apple and drunk a glass of orange juice the night before, he could still have survived. An apple and a glass of orange juice cost 3 cents back then.

In spite of his marital infidelities, he actually does play quite a good game of golf when everything’s clicking. So he didn’t lose his entire fan base when those infidelities came to light. But this lister met him once, in Pinehurst, NC. Well, met him, more or less. I, FlameHorse, was just a member of the crowd behind him as he teed off at the sixth hole, and because I have a loud (but rather pleasant), bass voice, Woods looked up at me as he was walking to the tee. He didn’t smile. He just glared. He glared at everyone. He did not tip his hat until he saw that his tee shot was good. Really, he was tipping his hat to the ball, not the crowd. And on the subject of tipping, Woods apparently loathes having to do it. So much so that many times, according to the rampant stories, he simply doesn’t. He is worth around $600 million, as of this list, down considerably from his peak of $1 billion. And yet, once when he was about to tip a restaurant waitress $5, he remembered that he had already tipped her $5, and put the second bill back in his pocket. In the wake of his infidelities, which set the golf world on its ear, one of the hundreds of women who alleged affairs with him stated that he would take her out to dinner, and tell the waiter that he would like his meal for free, “because I’m Tiger Woods.” The waiters always scoffed, of course, but Tiger never stopped trying this, according to the scorned mistress. He never tipped more than $10, even after a $1000 meal, and sometimes did not tip at all. Other alleged mistresses quickly echoed this sort of story. He is a very skilled blackjack player, and once took a casino in Las Vegas for several hundred thousand dollars in one night, then took from his penthouse suite all the towels, soap, shampoo, coffee, stationery, even the toilet paper. He almost always refuses to sign autographs, even when asked by little children, and he is said to have been overheard telling a caddy, “If they don’t expect to pay for the autograph, I don’t expect to sign one for free.”

Whereas, the rest of the entries on this list seem to be simply unhappy about parting with their money, the Collyer Brothers were psychotic about it. In addition to their miserliness, they were also extremely compulsive hoarders. They were born in 1881 and 1885, and both died within a week or so of each other, in 1947, in a sensational situation of insanity and noisome squalor. Homer, the elder, earned a degree in law from Columbia University. Langley claimed to have one in engineering from Columbia, but there is no proof. They were both very intelligent, inherited what today would be worth about 2 to 3 million dollars, and as the years went on, they both degenerated into lunacy. When their father abandoned the family and moved into a new house, his wife followed, and the brothers simply stayed in their parents’ old house, in Harlem. When their parents died, despite having a mountain of wealth, they simply brought all their parents’ belongings to the Harlem house and lived there for the rest of their lives. Neither ever married. They probably died virgins. Once the neighborhood started the rumor mill about valuables inside the brownstone house, people would idly throw rocks and bricks through the windows, looking for a way in. Langley proceeded to booby trap the entire house, all three stories of it, with whatever supplies availed themselves. After some 50 years in that house, they had acquired 130 tons of worthless junk from all over NYC, with which Langley was able to fashion some very elaborate traps, most of them involving 100-pound bundles of old newspapers hanging from 10 feet. Their utilities were all turned off for lack of payment on the bills, even though they could easily afford them. Once the house became an eyesore and a fire hazard, the Brothers refused to pay the bank the mortgage on their house. So the city attempted to evict them, until Langley simply wrote a check for all their utility debts and the mortgage, $6,700. Today, that would be about $90,000. The check did not bounce. That was in 1942. Five years later, they were dead. On March 21, 1947, a fetid stench began annoying the neighborhood, so the police were called to the house. They could not get in, because after breaking in through the doors and windows, they were faced with colossal, filthy walls of junk from floor to ceiling, so much of it that they could not immediately locate the source of the stench, noting that it was more than would emanate from a rat. It took 2 solid hours for a policeman to crawl through the house to Homer’s body, sitting slumped over in a decrepit chair, naked except for a bathrobe, shaggy beard and hair down to his shoulders. His fingernails were six inches long. He had starved to death, being so arthritic that he could not get up. But he was not the source of the stench – Langley was. A manhunt was ordered at first, but he was not found for 3 weeks. His body was only 10 feet from Homer’s. It took that long to remove all the junk from that room of the house. Langley had died by being crushed under one of his own newspaper traps, attempting to bring peanut butter and bread to Homer. The junk they had taken from the streets and derelict buildings during that time amounted to a value of less than $2,000. The rest was simply burned. They had been living like this, despite their dazzling wealth, for half a century.

Green is a stockbroking legend. She was nicknamed “the Witch of Wall Street.” She preferred to wear a long, flowing black dress, and upon her death only one was found in her wardrobe. She wore it day after day, rarely washing it or herself. She was worth some $200,000,000 at her death, in 1918, which today would be worth somewhere around $3.5 to 4 billion. She was one of the finest talents in the history of business, adhering to her philosophy of conservative buying backed by substantial cash reserves. She bought shares of railroads, and real estate, and she had so much money that she personally bailed out all of New York City on at least 3 occasions, writing checks for millions and taking short-term revenue bonds in repayment. But for all her fabulous wealth, she loathed spending for anything. She offered a preview of coming attractions before entering the investment world: her aunt was worth $2 million, which she willed to various charities, among them an orphanage and children’s hospital. Green sued over this will, producing one her aunt drew up years before, willing everything to Hetty, and then proceeded to take the money back from the charities. She lived for years in her Wall Street office, to save on heating her apartment, and ate cold oatmeal she warmed up on the office radiator. She personally set out from New York to Iowa once, by herself, via a single-horse buckboard wagon to collect on a debt of $350. When she arrived, the man who owed her had just died. She collected it from his grieving wife. She then traveled back the same way, sleeping in wooded areas beside the roads when the weather permitted. This was a time when women dared not travel alone, but she was armed with a revolver and a shotgun, both of which she borrowed from a Wall Street colleague. Her most infamous moment of stinginess came when her young son, Ned, broke his leg and required medical treatment lest he lose the limb. Green took him to a free hospital intended for the homeless, and told them she had no money. They treated him for one day before someone recognized her and demanded she pay. When she insisted she was not Hetty Green, the doctors threatened to call the police, whereupon she paid her bill, took Ned home and attempted to treat his leg herself. This didn’t work, and after years of her quack methods of poultices and vitamins, his leg had to be amputated. A few years before she died at the age of 81, she suffered a severe rhomboidal hernia (mid to lower back), and refused to have it treated for $150, insisting on coping with the pain. She died of a series of strokes culminating in a hemorrhagic argument with a housemaid over the fact that skim milk is just as nutritious as whole milk, and half the price.

Charles Dickens is believed to have been inspired to create Ebenezer Scrooge after reading about John Elwes. Elwes (no relation to the guy from The Princess Bride) was a member of the lower House of Parliament from 1772 to 1784, dying at 75 years old, in 1789. He inherited all of his wealth from his father and uncle, a total of some 350,000 pounds sterling, which, today, would be worth around 19 million pounds. He did not seem to have much of a problem loaning money to friends and colleagues, many of whom conveniently did not pay him back, and nevertheless, his investments increased in value until his death. He left an estate to his illegitimate sons, amounting to 500,000 pounds, or about 28 million pounds today. That’s about $43.5 million dollars. Yet for his entire adult life, he managed to live on less than 50 pounds a year. He wore the same clothes day after day, regardless of how offensive his stench was to others, and only bathed in the Thames River, rather than have water carried to his country mansion (an inherited mansion) and heated up over a fire. As such, he was only able to bathe in warm weather, which required that he spend the entire winter without washing. He saw nothing wrong with this. He found it intolerable that sparrows stole his hay for nests, and he liked to hunt them around his estate. When visitors came, he would secretly steal his hay from their horses to conserve, despite the fact that this is one of the very few uses hay had back then. He bought only what food was cheapest and drank only water. He would eat off a wild deer carcass for months, even after putrefaction set in, simply cooking it longer to be sure it would not make him sick, which it frequently did. He almost never kept house servants for long, because of the squalid living conditions and meager pay he expected would suit them. He walked in the pouring rain, rather than buy an umbrella, and often sat at supper in his soaked clothes, instead of spending firewood to dry them. He did have a nearly permanent housemaid, who claimed to witness him eat a small hen that a rat dragged out of the Thames. She died of overwork and malnutrition. He refused to pay for the upkeep of his mansion, letting it crumble to ruins around him, until it was condemned as a fire hazard. The chimneys collapsed and knocked holes in the roof, but he would not have anything fixed. By that point, near the end of his life, his realty investments had enabled him to buy other mansions and cottages in the countryside around London for profits that did not eat into his inheritance. Not one of these properties did he have kept up. When his family’s mansion was deemed unfit to live in and condemned, he simply moved into one of his other properties and lived there, regardless of how unfit it was to live in. By the time of his 70s, the walls of all his houses were crumbling in; the roofs had fireplace-size holes in them, and he simply moved from one bedroom to another to sleep where there was shelter. He refused to light fires for warmth, preferring an extra blanket or two. He wore the same clothes for so long that people mistook him on the street for a common beggar and gave him pennies, which he gladly kept. On his deathbed, rather than send for a doctor, he sent for a lawyer to draw up his 800,000 pound will, whom Elwes forced to work by light of the fireplace (as it was too cold even for multiple blankets), rather than light a single candle. He once loaned 7,000 pounds to a colleague for a bet on a horserace at Newmarket. On the day of the race, Elwes rode alone on his own horse, rather than rent a carriage, from Suffolk to Newmarket, which was 14 hours one way by horse. The racehorse was a long shot, and not only lost the race but dropped dead of a heart attack on the racetrack. During his entire trip to the races, Elwes refused to stop anywhere for food, but instead found a piece of cooked pancake in his coat pocket that had been there for 2 months – he happily ate it. He often rode to and from work at the House of Parliament on the same, underfed horse, with only a single hard-boiled egg in his pocket for lunch or supper. In his last years, he moved lodging between several of the unrented cottages he owned, sleeping without heat and almost no furnishings. He didn’t even pay for glass to be installed in the windows. He died of old age and malnutrition, complicated by exposure to the cold, on November 26, 1789.