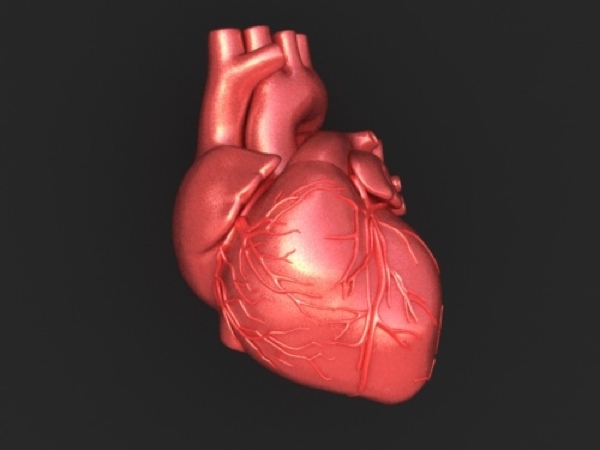

Our actual hearts do come close to the Valentine shape. But if you’ve ever seen a real human heart, it’s just as disgusting as any other organ inside you. Even cleaned up and not bloody, it’s raw, visceral, and thoroughly unromantic. The valentine shape works the same way as a Disney cartoon character. Lions are majestic animals, but not quite so perfectly beautiful as in The Lion King (their hair is not parted in the middle, and their fur is not always spic and span). Except for the red color, all aspects of blood are removed from the valentine shape rendering it no longer disgusting, but still representing what the ancients always thought of the heart: the Greeks believed that as the mind was the center of logic, the heart was the center of emotion and the soul. It is, after all, centered in the chest (and leaning slightly to the left).

Let’s keep the laughter to a minimum. The external female organs are collectively referred to as the vulva, and altogether, they form a nearly perfect upside down Valentine heart. The narrow point of the heart is situated precisely on the clitoris, and the lobes of the wider end at the bottoms of the labia majora. The implication is obvious, but deserves more research into the history of this correlation; it might prove fascinating. The female genitals were painted or inscribed on the outside doors of brothels in Pompeii, and can be found perfectly preserved there today. Their appearance was simplified to the Valentine heart, which is why sailors frequently used the symbol as a tattoo. Sailors were at sea for months or years without women, so when they hit a port, sex was one of the first things on their minds. When the tattoos were questioned by family (wives), they were usually euphemized as just a symbol for love.

Testicles all look the same, really, and if this particular theory is true, it more likely stems from the handling of livestock than human testicles. Livestock testicles, after all, rarely grow coarse hair as humans’ do, and as such, are very easy to examine. Centuries ago, castrating livestock was not as technological an affair as it is today: no anesthetic, no pliers to crush the cord; just a knife and a prayer that the animal would not die. Livestock owners typically did this job themselves to save money, and few were professionals. The testicles were grasped together at the bottom of the scrotum and simply sliced off. Testicles are elongated ovoids, somewhat tapered at the back end, wider at the top. When they are pressed side to side, the tapered ends form the rudimentary point that is the bottom of the Valentine heart, and the wider ends form the top lobes. It may have occurred to someone that because they are part of the man’s erogenous area, they could be seen as a source of romance. You will find testicles stylized as inverted Valentine hearts on some coats of arms, such as the Colleoni family of Milan. The implication is that a man sends a Valentine heart to a woman as a subconscious offering of his reproductive future; likewise, a woman sends a heart to a man as a subconscious desire for it.

The Valentine heart is already a good approximation of a broad head for arrows. In keeping with the theories of numbers nine and eight, Cupid, the Roman god of physical love-making, is classically depicted firing arrows at people. Anyone struck with the arrow falls in desperate, nearly uncontrollable love either with the nearest person to him, or with the person who prayed to Cupid to find love. Widespread dissemination, in all types of art, of the Valentine heart began in the 1400s (but see item one) with Renaissance painters, and many of those depictions were of winged Cupid the baby or boy at play stirring up love with a bow and arrow. He is obviously a good shot, and it is understood that he shoots the victim right through the heart, the center of emotion and passion. The arrowhead is frequently seen as somewhat softened; a sharply pointed and edged iron hunting tip is not very romantic, so the two rearward pointing barbs, meant to prevent the head from being withdrawn from the target, were rounded into lobes, and suddenly, the arrowhead does not look quite so vicious.

The general shape of the torso is no less similar to the Valentine heart as the actual human heart. The shoulders of both men and women are meant to be wider than the waist, especially when the person’s chest swells with a deep breath. This creates the rough, isosceles triangle, odd vertex down, and it only remains to refine by sinking the horizontal top. The eye traces down and in from the shoulders along the collarbones, and the sump between the Valentine heart’s lobes is understood to be at the top of the actual heart, where love is popularly thought to originate.

There is more than one position for kissing, but the classic example involves the chests pressed together, arms intertwined or around the back, and noses touching (no face tilting). When this position is reached, the two people can form a perfect Valentine heart of space between them, and the shape is centered between their real hearts. This affords another good list idea: why do we kiss?

If you invert a Valentine heart, the wide, rounded lobes look just like a butt. Sir Mix-a-Lot approves of big butts, and it is his avowed opinion that when a woman walks in with an itty-bitty waist and a round thing in your face, you get sprung. So the buttocks themselves are no more important than the narrow waist above them, and the Valentine heart appears just like this. Why it would have been inverted over time is difficult to say; maybe someone found it more aesthetic with the wide part at the top, and it caught on. Man’s arousal by a woman with a narrow waist and wide hips may stem from the principle that wider hips have a vastly easier time of giving birth.

The human heart is roughly triangular, wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, and the Valentine heart approximates this, but with two rounded lobes at the top, which is distinctly different from the real thing. The rest of the shape tapers to the bottom point, and altogether, it’s a fair abstraction of a woman’s breasts pushed together probably by a corset, which was popular among men and very unpopular among women from the Renaissance on. The corset is designed to constrict the breasts and mash them up toward the collar, so whatever breast size a woman sports, all of it is enhanced for the benefit of the men around her; it also compresses the abdomen and waist uniformly, giving the woman what is thought of as the perfect hourglass figure. The disadvantage is that it also constricts her ability to breathe, which is why women fainted so easily in the old days. The reason women’s breasts arouse men is a good question, but probably has to do with the primitive instinct to make babies with a woman who can promise them a lot of milk.

Not that swans are the mascot of Valentine’s Day, but we think of them as symbols of grace, elegance, beauty, and calmness; their down-turned necks make them appear humble and demure, and this was how women were expected to act back in the day. The classic picture of two swans facing each other with bills touching is a very popular one for Valentines, and swans do this quite often. They’re smelling each other’s breath to remember who’s who (swans can appear identical and sometimes get confused, just as we confuse them). Mated pairs also neck as a way of bonding. They are generally monogamous and mate for life, and if you’ve ever wondered if animals feel grief and sadness, yes they do. Male swans are just as aggressively protective of their mates as we are.

Silphium was a well known herb, probably extinct today, used extensively across the Mediterranean for spicing food and as a deliberate abortive agent in women, a sort of birth control pill. The day after sex, the woman would eat the silphium plant, usually cooked, and/or seeds. We have no direct evidence of the plant’s ability to cause a miscarriage, since we cannot find any specimens, but indirect evidence in the way of contemporary literature strongly indicates that silphium was highly reliable in aborting pregnancies. It only grew along a stretch of the northeastern Libyan coastline, the climate of which has become markedly drier over the millennia. By the time of Nero, Pliny the Younger claims that the plant was extremely difficult to find, and possibly the very last specimen was presented to the Emperor, which he had prepared for his supper. The silphium seed has survived to us, minted on Cyrenian coins, and it grew as a perfect Valentine heart.