Of course, Mary Mallon was “Typhoid Mary.” Some people view her as a victim, others as an unrepentant killer. Certainly, her story has much to do with the lack of information about and treatments for typhoid in the 19th century. Even today, typhoid infects about 22 million people each year, with about 200,000 dying, especially in developing countries. And we have vaccinations and treatments for this deadly disease now. So, is it any wonder that Typhoid Mary could strike such fear into 19th-century hearts?

10 Typhoid Fever Was One Of The 19th Century’s Worst Killers

In the 19th century, diseases spread rapidly in New York City where horses dropped massive amounts of manure on the streets each day. By 1894, the manure problem had reached crisis proportions in major cities across the world. According to one estimate, New York City’s horses numbered at least 100,000 (and probably considerably more) and were polluting the streets with at least 1.1 million kilograms (2.5 million lb) of excrement each day.[1] Dead and decaying animals also lined the streets. Families squeezed together in tenement buildings with overflowing outhouses. All these factors combined to hasten the spread of typhoid fever. It invaded the stomach and small intestines, causing infections in the liver, gallbladder, spleen, heart, lungs, and kidneys. The deadliest damage occurred in the intestines. In severe cases, patients became delirious and developed severe diarrhea. Typhoid killed 10–30 percent of its victims, and their deaths were agonizing.

9 Dr. George Soper Became A Germ-Fighting Celebrity Hero

Dr. George Soper studied typhoid fever. He wanted to know what caused it, how it spread, and how to stop it. Soper promoted himself as a “sanitation engineer and chemist.” Soon, companies were hiring him to investigate germs and the spread of disease. In 1903, there was a typhoid outbreak in Ithaca, New York. All over town, people were bedridden. Over a dozen patients a day were admitted to the city hospital. It was especially alarming that many of these were college students. Approximately 1,000 students, over one-third of the student body, at Cornell University evacuated the campus due to the deadly disease.[2] Soper went to work. He knew he had to stop sewage from polluting streams, rivers, and wells. He identified an area known as Six Mile Creek as the source of the outbreak. After insisting that all water be boiled, he recommended the use of a new filtering system for the city’s water. He also ordered a massive disinfection of area hospitals and hired a team of 15 men to clean 1,200 outhouses. Many people credited him with restoring health to Ithaca and Cornell University.

8 Typhoid Fever Spread Wherever Mary Went

The Warrens were an affluent family renting a vacation home on Oyster Bay on Long Island. There were six family members and five servants. When six people contracted typhoid fever, no one blamed the cook—at first. The Thompsons, the owners of the home, hired George Soper to investigate. After analyzing the water supply and the family’s food, he turned his suspicions on Mary Mallon, the family’s former cook.[3] Further research revealed that Mallon had worked for eight families. Seven of them faced outbreaks of typhoid fever, with 22 cases in all. While this seemed an unlikely coincidence, Soper knew that he would need more proof. In fact, he needed help from Mary Mallon.

7 Typhoid Mary Was Violent

George Soper was on a mission. He paid Mary Mallon a surprise visit at her current employer’s home. After telling her that he represented the New York City Health Department, he explained that she was infecting people with a dangerous disease. He requested that she supply urine, stool, and blood specimens.[4] Mary became angry. She cursed at him, grabbed a carving knife, and lunged toward him. Soper ran from the house. He thought Mary might respond better to a woman. So he sent Josephine Baker, one of the first female physicians, to talk to Mary. (Some sources say that Hermann Biggs at the health department sent Baker.) Either way, her visit was also disastrous. Baker reported, “She (Mary) came out fighting and swearing, both of which she could do with appalling efficiency and vigor.” When Baker returned with police officers and an ambulance, Mary tried to stab Baker with a large kitchen fork. Then Mary kicked, screamed, and swore at the police officers. To keep Mary from escaping, Baker sat on her chest, pinning her to the floor of the ambulance. Later, Mary wrote threatening letters to George Soper and Josephine Baker saying that she planned to take a gun and kill them.

6 Mary Mallon Was Taken By Force

Mary Mallon was taken against her will by force and held without a trial. After policemen put her into the ambulance, Mary traveled to Willard Parker Hospital where she had to give urine, stool, and blood samples to prove that she was a carrier of typhoid fever. Throughout the examination, Mary insisted that she was healthy. She did not understand how she could spread a deadly disease. She was sure that she had never had typhoid fever. Walter Bensel of the New York City Health Department declared, “This woman is a great menace to health, a danger to the community, and she has been made a prisoner on that account.”[5] After completing their examination, hospital employees escorted Mary to a boat. The steamer carried her to North Brother Island, which belonged to Riverside Hospital. This remote island was in the middle of the East River and accessible only by boat. Escape would be impossible. The facility quarantined people with infectious diseases like typhus and smallpox. Mary lived in a small bungalow along the riverbank. This was her home for almost three years.

5 Soper Offered To Release Mary If She Would Have Her Gallbladder Removed

While at Willard Parker Hospital, Dr. Soper visited Mary and offered her a deal. Since most of her germs were in her gallbladder, they could release her if she agreed to have this organ removed. He explained that the gallbladder was like the appendix. The body didn’t need it to survive. Mary refused to let doctors operate. “No knife will be put on me. There is nothing the matter with my gallbladder,” she declared.[6] Of course, surgery always has risks. But they were even greater in the early 1900s as shown by the picture above of a surgery performed in 1900. No one even wore masks. The operating room and procedures were not hygienic, especially by today’s standards. Mary was becoming increasingly suspicious of doctors. And who could blame her?

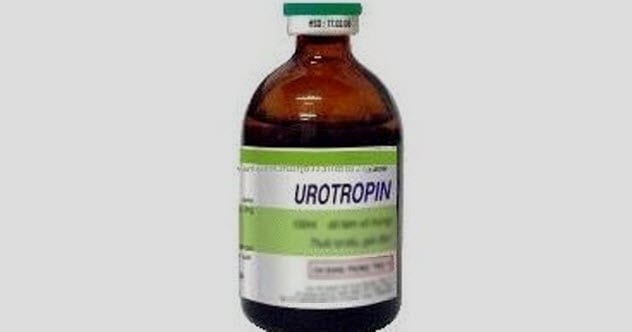

4 The Health Department Used Experimental Drugs On Typhoid Mary

Doctors prescribed Urotropin, a drug made from ammonia and formaldehyde.[7] It was not effective. Mary found the side effects to be unpleasant. Doctors also experimented with other drugs, changed her diet, and gave her laxatives. Tests showed that she was still a typhoid fever carrier.

3 Mary Received A Marriage Proposal While Quarantined

Reuben Gray, a 28-year-old Michigan farmer, wrote to Health Commissioner Thomas Darlington. Gray had read about Typhoid Mary. He wanted to marry her and offer her a home on his large farm far from town. There, Mary would not put other lives in danger. Gray knew that Mary was a good cook. That was what he wanted most in a wife. “One thing she should be made aware of before the tie is bound,” wrote Gray, “and that is that I have been insane, but it was over three years ago.”[8] Mary declined his offer.

2 Mary Was Sneaky

In February 1910, Ernst Lederle, the new health commissioner, offered Mary a deal. If she gave up cooking and reported to the health department every month for tests, she would be released. For the first year, Mary observed all the rules. She reported monthly to the health department. She did not work as a cook. But she struggled to find work and make a living. Cooks made more money than other domestic workers. When Mary stopped reporting to the health department, no one noticed at first. She changed her name to Mary Brown and took several jobs as a cook. In 1915, five years after Mary’s release, there was a typhoid outbreak at Sloane Hospital for Women (renamed from Sloane Maternity Hospital in 1910) in Manhattan. Twenty-five people were diagnosed with the disease. Two of them died.[9] Once again, Dr. Soper investigated. He discovered that the hospital had hired a new cook, a Mrs. Brown, just three months before the typhoid fever cases surfaced. Investigators tested the kitchen staff. Mrs. Brown’s test was positive. Soper became more suspicious when he learned that the cook had disappeared again. Soper examined the kitchen’s records and soon recognized Mary’s handwriting from the threatening letters he had received. This time, the public became angry. The Board of Health sent Mary back to Riverside Hospital. She lived there for 23 years. After a stroke left her paralyzed, she was transferred from her cottage to the hospital on the island. She stayed there until her death on November 11, 1938.

1 Mary Was Neither The Only Carrier Of Typhoid Nor The Most Deadly

Mary Mallon was the first typhoid carrier to be identified. However, by 1909, the New York City Health Department had found five healthy carriers. Only Mary was quarantined. She was believed to have infected 47–51 people, causing three deaths. However, Tony Labella, another healthy carrier of typhoid fever, had infected 122 people (over twice as many as Mallon had). Five died. He was quarantined for two weeks and then released. At age 39, he disappeared. The Health Department also forbade typhoid carrier Alphonse Cotils, a restaurant and bakery owner, to prepare food for other people. When he violated orders, charges were filed. Yet, the judge did not arrest him because he had a wife and children to support. At the time, up to 4,500 new cases of typhoid occurred in New York City each year. Approximately 3 percent of sufferers were believed to become carriers. As a result, as many as 135 new typhoid carriers appeared each year. Mary Mallon may have spent most of her life in isolation, but she was far from alone in becoming a carrier of typhoid fever.[10] Lou Hunley is a children’s librarian. She loves learning more about strange historical events. When she’s not reading or writing, she enjoys hiking, biking, and playing pickleball.