While the U.S. doesn’t have quite as long of a history, it does boast its own ancient afterlife. And the burial grounds that go along with it are fascinating. Historians across America study old cemeteries to learn about the past. The stories they’ve unearthed are both unsettling and amazing. In this list, you’ll learn about ten of America’s oldest graveyards and the supposed spirits who stay within. These centuries-old cemeteries are seriously spooky!

10 NYC’s Old Gravesend Cemetery

New York City has a very long history. It’s also a modern-day travel destination and business hub. So you wouldn’t be wrong to think much of the historic Big Apple has been paved over and renovated. But not everything in NYC is moving forward. In fact, there are quite a few old cemeteries scattered across its boroughs. The city’s first Dutch settlers are buried in graveyards that date back to the 17th century. The Old Gravesend Cemetery in Brooklyn is one of the oldest of those. The area around it was first established in 1643. The first mention of Old Gravesend itself was in a will dated 1658. So while the cemetery’s founding date isn’t precisely known, it likely came about in the 1640s. In total, there are 379 gravestones at the site. City officials have been working on renovating the stones. Upkeep is costly, but the history that comes with it is immeasurable. The cemetery’s most famous resident is (probably) Lady Deborah Moody. She was the surrounding settlement’s founder and first settler. In fact, she was the first woman to establish a community of Dutch immigrants in all of New England. Well off during her life, Moody originally left Holland to settle in Massachusetts. But once there, she clashed with the Puritans. They didn’t like her belief in adult baptism. And her work to convert people was viewed as unseemly. So they cast her out, and she traveled down to New York. At the time, the area was known as New Amsterdam and had a heavily Dutch population. Moody fit right in and settled in the Gravesend area of modern-day Brooklyn. But as well known as she was at the time, it’s unclear whether Moody is buried in the graveyard in her adopted home. It’s probable, but historians have no definitive proof of her burial there. Considering the age of the burial ground, it’s likely that the mystery will never be solved.[1]

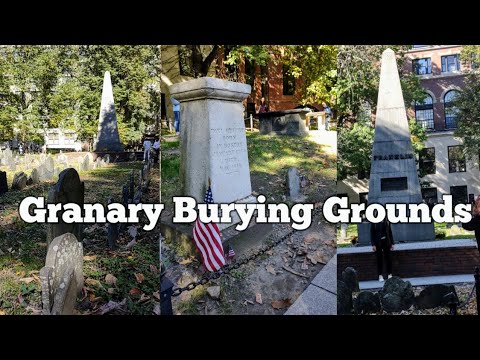

9 Boston’s Granary Burying Ground

Much like New York City, Boston’s bustle is forever moving forward. And much like New York City, Boston has its own incredible past. The Massachusetts city is full of old cemeteries, just like others up and down the Eastern Seaboard too. In Boston, one of the oldest is the Granary Burying Ground. That name was officially christened in 1737, but the cemetery site was around nearly a full century earlier. For over 200 years, until the 1880s, notable Bostonians were buried in the Granary Ground. In total, about 5,000 people were laid to rest on the site. Not all the grave markers have lasted the test of time, though. Today, officials estimate about 2,300 stones are still in order. The disheveled history of those headstones took an interesting turn in the 1800s. In the middle of that century, Bostonians were frustrated with the disorder of the grounds. So, they set about a years-long project to rearrange and set right thousands of headstones. Some were moved and misplaced. Others were accidentally destroyed in the clean-up. Today, the site is far more orderly. However, it’s unclear whether every headstone is actually in its original spot. Nevertheless, the Granary Burying Ground keeps on playing the hits. Paths inside the cemetery take scores of visitors on an incredible tour. Samuel Adams, John Hancock, Paul Revere, and Crispus Attucks are all buried in the cemetery. American history truly rests in the Granary Burying Ground.[2]

8 Texas’s Ernest Witte Site

New York and Boston hold historic cemeteries, but they aren’t the only ancient graveyards in America. In fact, there are far older burial grounds scattered elsewhere across the U.S. And the oldest of them all can be found in Texas, of all places! In the 1970s, historians found an ancient Brazos River burial ground. Today, it is known as the Ernest Witte Site. Archaeological evidence suggests the area was first used as a cemetery nearly 5,000 years ago. Scientists believe the final burials there happened around AD 1500. Some of these fossils were buried with primitive stone tools. More recent burials came with the presence of shell jewelry, carved stone knives, and animal skulls. The site is now a treasure trove of archaeological information about life in pre-contact America. The story behind the burial site’s name is its own fascinating tale. Ernest Witte was a young boy growing up in rural Texas in the 1930s. One day, in the middle of the Great Depression, Witte and his brother were rooting around an area near the Brazos River. Accidentally, they uncovered some fossils. Not knowing what they found, they kept digging. Slowly but surely, they uncovered more ancient artifacts. But here’s where it gets really crazy: The brothers never told anyone about it! For decades, Ernest kept the site a secret. Finally, in 1974, he reached out to the Texas Archaeological Survey. Shocked scientists flocked to the site and began digging. They’ve since found the remains of roughly 250 people at the site. The historical value has been immense. But it was nearly lost to history forever![3]

7 West Virginia’s Grave Creek Mound

West Virginia boasts its own ancient burial site. Grave Creek Mound sits in the far north part of the state, close to the Ohio border. The nearby town of Moundsville is named for it. And if you haven’t already guessed by now, the burial site is one big mound. There’s more to it than that, though. Archaeologists have determined the graves contained within date back to about 250 BC. They are the graves of members of the local Adena tribe. When the culture was thriving, the Adena buried their dead in these raised mounds. The sheer size of the Grave Creek Mound is stunning. Scientists believe tribe members moved nearly 57,000 tons of soil to create the hill. The Adena also built smaller mounds set near the large earthen dome. In those, they placed meaningful trinkets and mementos like jewelry and religious items. For centuries, the site was their solemn way to honor the dead. Sadly, looters got to Grave Creek Mound before archaeologists did. While science has preserved many things from the dirt structure, many more have been lost to history. Through the 18th and 19th centuries, looters raided the smaller mounds. They took trinkets, sea shells, ivory beads, copper bracelets, and other things that had been left centuries before. Thankfully, some items remained. Plus, layers of burials within the mound itself gave archaeologists plenty to learn. Today, historians have been able to piece together a lot about the Adena despite these setbacks. But much of the mound’s earthly items remain a mystery. Researchers wonder what they missed out on after decades of grave robberies.[4]

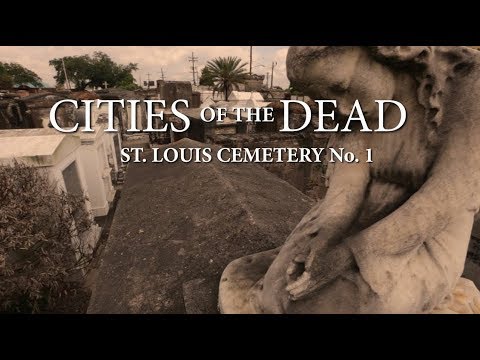

6 New Orleans’ St. Louis Cemetery No. 1

St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 may be the most memorable graveyard on this list. It’s a striking sight to see. Rows of above-ground tombs dot the tightly-packed cemetery. It is full of historic New Orleans flavor and mystery. Stories of haunted spirits and rumors of ghastly ghosts abound. The cemetery isn’t the oldest in New Orleans, but it’s close. It was first built way back in 1789. A series of fires and a brutal epidemic had just ravaged the Big Easy. City officials were worried existing cemeteries couldn’t hold all the dead. So, St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 was created. At first, the dead were actually buried underground. But in 1803, New Orleans levied a law ordering all new burials must be done above ground. Since its founding, the low-lying city has been subjected to waves of flooding. Having a bunch of human remains wash up was fast becoming a public health nightmare. And so the tradition of the raised tombs began. Just like Old Gravesend in NYC, St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 has a notable soul inside. Marie Laveau was born in New Orleans in 1801 to a Creole mother. As an adult, she worked in town as a hairdresser. But she was far more famous in the region for her side gig as a voodoo priestess. People in New Orleans swore by the spells she cast and the mystical powers she supposedly held. Before she died in 1881, Marie was a local legend. When she was buried in St. Louis Cemetery, locals still tried to seek favor from her spirit. For decades after, mourners came to the graveyard to visit her tomb. Once there, they would paint large Xs on the tomb door. The city made the practice illegal, but that didn’t stop the superstition. Even today, Laveau’s legend lives on.[5]

5 Providence’s North Burial Ground

The North Burial Ground has been in Providence, Rhode Island, since about 1700. Long before America was a nation, settlers came to Rhode Island. On the north side of its historic urban center, planners set aside 45 acres for a cemetery. One of the first burials was that of a prominent settler named Samuel Whipple. Over the next few years, many more locals followed. Eventually, the North Burial Ground became the place to lay the city’s elite leaders and residents to rest. Over the next century, Providence consolidated other burial grounds. Historically, well-to-do families buried their dead on their own plots of land. But as Providence grew, that custom became inefficient. So in 1785, the city’s elite residents exhumed the bodies of many of their ancestors and elders. All the remains were carefully carted away and re-buried in the North Burial Ground. In the decades after, many more prominent citizens were laid to rest in the cemetery. Since then, the graveyard has undergone many renovations. Further grave relocations have swept in too. In the 1980s, the city even (briefly) lost a headstone after a car accident ran aground in a corner of the cemetery. Over the years, many high-profile people have been buried within. Veterans of both the Revolutionary War and the Civil War rest there. More recently, famous Americans like pioneering outdoorswoman Annie Smith Peck and early goth poet Sarah Helen Whitman are buried there too. And today, the North Burial Ground still accepts new burials. That is rare for a 300-year-old cemetery! But the site is still active. It takes in about 200 sets of remains every year. And every year, newly-deceased Providence residents add their own life stories to the hallowed ground.[6]

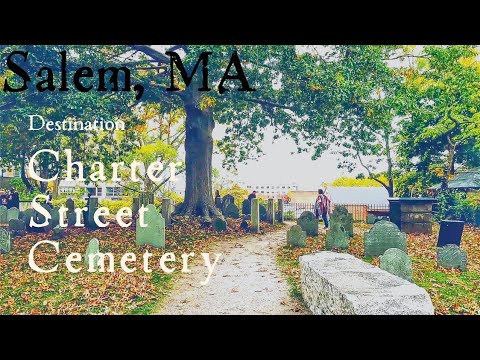

4 Salem’s Charter Street Cemetery

Whenever one says “Salem,” the implication is clear: witchcraft. The Massachusetts town was famously the supposed center of witchcraft in the 17th century. But the city has ghost stories far older than that! In fact, Salem’s Charter Street Cemetery predates the witch trials by more than six decades. The burial ground, which is known to locals as Old Burying Point, was first mentioned in written documents in 1637. Historians now think the context of that reference indicates it was around long before that. So while its founding year is unclear, this analysis suggests Old Burying Point is the oldest European cemetery in America. The oldest surviving headstone on site belongs to a woman named Doraty Cromwell. She died in Salem in 1673. That her gravestone has survived this long is a miracle. Early American memorials were usually made out of wood. Thus, most haven’t survived centuries of winter snow, spring rain, and summer sun. Before Cromwell, it’s impossible to know who else was laid to rest at Old Burying Point. Thankfully for genealogists, grave markers have long since switched to stone. Historians do know one thing, though: Salem’s supposed witches were not buried at the Charter Street Cemetery. They were put on trial very close by in 1692. And Old Burying Point was already well-established as the city’s cemetery by then. But those found guilty of practicing witchcraft wouldn’t have been given a public burial in an esteemed location. It’s far more likely they were buried secretly by sympathetic family members. If no one stepped up, these accused witches were thrown into unmarked graves near their trial sites. For them, a well-regarded rest at Old Burying Point was never in the cards.[7]

3 New Mexico’s San Esteban del Rey Mission Church

Decades before American colonists kicked off their anti-British rumblings back east, Spanish explorers were making their way through the southwest. In 1629, they founded the San Estévan del Rey Mission in what is now western New Mexico. Back then, the land belonged to the Acoma Pueblo people. The Spanish intended for the mission to bring Catholicism to the natives. Part of the Spaniards’ hopes centered on the afterlife: They wanted indigenous people to follow the church’s burial customs. For decades, the Spanish tried to attract the Acoma Pueblo to their lifestyle. The visitors had some success until the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Then, for two decades, the natives took control of the mission and mostly shut down the Spanish incursion. As for the cemetery on site, its creation is a story unto itself. The area sits on a mesa of bare rock with little topsoil. Opportunities for agriculture are sparse and limited. Even worse, in-ground burial is next to impossible. The Spanish solved this by forcing natives to carry tons of soil up the rocks to spread on top. Once the covered area was deep enough, it was packed down. Then, Spanish settlers could adequately bury their dead at the mission. Today, the cemetery consists of five of these levels. Some reach 50 feet (15 meters) above what used to be the natural rocky ground. Different settlers and natives throughout history are buried there. The Acoma people got their way in the end too. Even though the mission is of Catholic origin, locals managed to sneak in a few of their traditions over the centuries. Today, mission visitors can see sculpted faces inside the cemetery’s walls. These are guardians that carry native spirits safely into the afterlife. One section of the graveyard wall also has a large hole. There, spirits are said to freely leave the site to take on eternal existence after death.[8]

2 NYC’s African Burial Ground

For nearly two centuries, New York City had a little-known cemetery meant for Black residents. Both enslaved and free Black people were buried there as early as the 1630s. The ground was active until about 1800. Then, the city stopped using it. Eventually, it was paved over and repurposed. For nearly 200 years, it was forgotten. Then, in 1991, construction began on a new officer tower along Broadway Avenue. As the ground underwent excavation, mass graves were found. Suddenly, the construction project became a critical preservation scene. Archaeologists rushed in and supervised the work. Further excavations found the graveyard covered more than six acres of space. Shocked at the discovery, historians termed it the African Burial Ground. Notable Black people are thought to be buried there. That list likely includes Juan Rodrigues, the first free Black man in Manhattan, who arrived in the city in 1613. Judging by the size of the area, historians estimate more than 15,000 people were laid to rest there. The remains include the first generations of slaves transported against their will to America. Today, it is the earliest known African cemetery in the United States. Thankfully, by 2003, all the excavated remains were placed in hand-carved coffins and properly reinterred.[9]

1 Massachusetts’s Myles Standish Burial Ground

The Myles Standish Burial Ground calls itself the oldest “maintained” cemetery in the United States. As we’ve already seen with some dubious dates on this list, that may be up for debate. But there’s no question this cemetery is very old. It appears to have been first established as early as 1638. Its location in the Massachusetts city of Duxbury has historical meaning too. The area is close to where the Mayflower first made land from England early in the 17th century. So it should be no surprise to learn that many of the Mayflower’s notable pioneering passengers are buried there. Other notable burials include he for whom the cemetery is named. Military commander Myles Standish was buried in it after he died near Duxbury in 1656. The man who played such a key role in protecting the Pilgrims during their early years in America is forever honored in the graveyard. In fact, his body has since been exhumed (twice!) to be honored with more significant memorials. In addition to Standish, the site hosts many old Pilgrim grave markers. They include some fascinating examples of historic Puritan imagery. As a group, they were obsessed with mortality. And boy, do their gravestones show it. Gravestone designs of unsettling angels, smiling death’s heads, spooky skulls, and outlined coffins all confront modern visitors. Creepy![10]

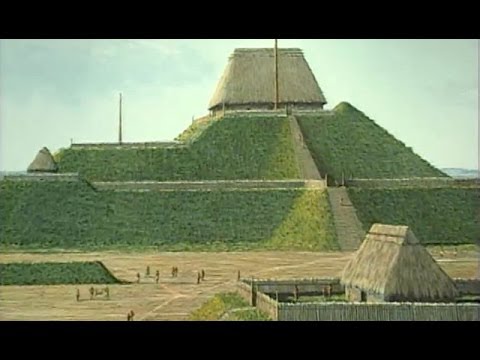

+ Bonus: Cahokia

You didn’t think we forgot about Cahokia, did you? While grave mounds in West Virginia and New Mexico made this list, they don’t compare to the most iconic of all. Centuries ago, southern Illinois’s Cahokia was the largest settlement in America. The sprawling indigenous city had everything. At its peak from about 600 to 1350, more than 15,000 people lived there. Watch this video on YouTube Cahokia had large residential neighborhoods, open spaces for events, large marketplaces, and even a permanent agricultural area. It also had a series of notable grave mounds. Today, historians believe the man-made hills were used for several purposes. Burying the dead was foremost among them, of course. But Cahokia residents also held religious ceremonies on the mounds and worshiped native gods from the top. Today, the biggest of these hills is known as Mound 72. Archaeologists have been working on that site since the 1960s. Over the years, they have preserved the remains of more than 270 people. Some were interred in mass graves. Others were given more ornate burials. Those buried in the most shallow graves appear to show signs of violent death. Interestingly, scientists believe those are also the most recent burials, dating to roughly 1300. Considering Cahokia was abandoned at some point in the 14th century, archaeologists think these burial mound findings point to a violent regional war that broke up the big city.[11]