The latter make the headlines more often. But ordinary civilians frequently stumble across artifacts that are unique, change history, or add considerably to scholars’ knowledge.

10 The Trajan-Augustus Coin

In 2016, seasoned hiker Laurie Rimon fancied a walk in eastern Galilee. When she passed through an archaeological site, a yellow glint caught her eye. In the grass was an old coin. After handing it over to authorities, Rimon was surprised to learn that it was around 2,000 years old. What made the find more exceptional was that only one other of its kind is known to exist. The extremely rare coin was minted in Rome during AD 107. Embossed on the gold were the faces of two Roman emperors. Trajan’s profile can be seen on the back surrounded by symbols. On the front, the words “Augustus Deified” encircled the face of Augustus. This made the artifact particularly unusual. In most cases, the emperor Trajan commands both sides of the coin. He was also the one who issued a series (the Trajan-Augustus type included) of different currencies as a show of respect to his predecessors. The coin will remain in Israel, as opposed to its identical counterpart which belongs to the British Museum.[1]

9 An Ancient Hideaway

One day, Beat Dietrich took his dog for a walk. As a warden of an alpine hut in Switzerland, it was not too strange that he strolled into a high mountain pass called the Lotschberg Pass. There, in 2011, he noticed old wood and leather. Archaeologists were able to have a brief look before snow made the site inaccessible until 2017. When excavations moved ahead, a rocky shelter was identified near the highest point of the pass, which is nearly 2,700 meters (8,800 ft) high. Inside, they found personal items left behind by an ancient mountaineer. Around 4,000 years ago, a hunter or herder (or maybe a small group) used the hollow. Then, for some reason, they left behind arrows and a wooden box that once contained flour. There were also four pieces of worked elm, which could have belonged to two separate bows. Other items included leather strips, as well as a button and container which were both made of horn. The Bronze Age collection contains the oldest artifacts ever found in the pass. They also provide physical evidence to back the claims that Lotschberg was used for centuries by traders, hunters, and shepherds.[2]

8 The Somerset Skull

Years after Beat Dietrich took his dog for a walk in the snow, another man treated his canine to an outing. Roger Evans’s walk along the River Sowy in Somerset ended with a group of suspicious cops. In 2017, Evans found a human skull. The authorities’ belief that foul play was involved had some standing—the woman had been decapitated. There was nothing that the police could do, though, considering that she had died during the Iron Age at age 45. Nothing is certain, but experts have a rough idea of what happened. The woman, who lived sometime between 380–190 BC, had her head hacked off. The cut marks show that it was a deliberate act. But it’s unclear whether it was done while she was alive or already dead. Neither her body nor other human remains were found. However, other decapitated skulls in water have been recorded elsewhere. Heads were revered in the Iron Age, and this one was likely placed in the river as an act of worship. The new find adds weight to the belief that a Celtic “head cult” existed during the Iron Age.[3]

7 Storage Cave Used For Millennia

After Alexander the Great died, things got hairy in Israel. His heirs fought each other in the Wars of the Diadochi. Around that time, 2,300 years ago, somebody hid valuable items in a northern cave. The hoard remained undisturbed until three men found it in 2015. Reuven Zakai took his 21-year-old son, Hen, and a friend spelunking. The day was an exercise to prepare for another expedition, but then Hen squeezed into a narrow space and found the hidden loot. Initially, he only noticed two coins, rings, bracelets, and earrings. Most were made of silver. The trio reported their find and returned later with members from the Israel Antiquities Authority. Together with the Israeli Caving Club, to which the three men belonged, another search was launched. It soon became clear that the cave, which was dangerous to navigate, provided vaults for more than just one hoarder. They found more artifacts, including ceramics, dating from 3,000 to 6,000 years ago.[4] Officials believe that those from Alexander’s era were placed there for safekeeping by locals caught in the aftermath of his death. Perhaps the owners were forced to abandon the treasure—or worse—because they never came back.

6 Chelichnus Gigas

A few years ago, Tom Cluff took friends into Nevada’s Clark County. He planned on showing them the fossilized footprints he had discovered. The hikers paused for a picnic lunch—and noticed tracks on the rocks below. But they were not Cluff’s prize find. The previous prints had been made by an invertebrate. The new line of footprints belonged to an ancient reptile. Called the Chelichnus gigas track, researchers hit a blank when they compared it to known species. However, the creature left two clues to its appearance. There were no drag marks, meaning the reptile either did not have a tail or kept it elevated. There were also three toes on each hind foot. Unfortunately, as with so many four-legged animals, its back feet marred the front marks by stepping on them. Today, the area is a desert. But when the creature wandered there 290 million years ago, the land was marshy. The 60-centimeter-long (24 in) reptile took six strides on something, most likely a microbial mat, which kept the shape of its feet even after they filled up with sediment.[5]

5 Montserrat’s First Petroglyphs

In 2016, another group of hikers decided to troop through a dense forest on the Caribbean island of Montserrat. However, the trip revealed more than just a walk through unspoiled nature. Somebody had beaten them to the area and left marks on a boulder. Luckily, it was not graffiti but the island’s first petroglyphs. Ancient rock carvings are known among the Caribbean islands, but none have ever been found on Montserrat. The island also belongs to the British Overseas Territory, where no petroglyphs have ever been found. The engravings resemble geometric shapes and some sort of beings. Researchers are not sure if the symbols have meaning but agree that they were sacred to Montserrat’s original indigenous people. Carved 1,000–1,500 years ago by Arawak Amerindians, who also left artifacts on the island, the petroglyphs resemble those on nearby islands.[6] The pre-Columbian people left in the 1400s to escape raids from the Caribs, another indigenous tribe. Both Arawak- and Carib-speaking communities still live in South America where similar etchings have been found near rivers. If this is indeed some kind of code, cracking it will enrich Montserrat’s unique history even more.

4 Scotland’s Rock Art Hunter

When George Currie went into semiretirement, the music teacher decided to spend some time looking for rock carvings. A few steps away from a well-known site, he found one. Most people who find ancient artifacts or sites do so by chance and then only once. However, when Currie heard that his discovery had not been previously recorded, it made him determined to find some more. Over the next 15 years, in every imaginable type of weather, Curry walked the moors, fields, and sometimes peeked into a cave. By 2016, he had “collected” over 670 of Scotland’s recorded 2,500 rock engravings. They were all dated from 4000 to 2000 BC. What struck him was the kind of surface the prehistoric artists preferred. Many designs had been carved on rough rocks when smooth stone seem like a better idea. Some carvers even incorporated surface cracks and bumps into the designs. Neither Currie nor researchers understand the purpose of the etchings or how rocks were chosen. Most displayed the well-known “cup-and-ring” marks, a circular design that appears all over prehistoric Europe. Currie’s contribution has been described as phenomenal and was recently included in Britain’s most intensive study to understand the region’s earliest art.[7]

3 Gzhelian Age Reptile

Inspired by the movie Jurassic Park in 1995, two boys hit the beach looking for fossils. At one point, Michael Arsenault fell on sandstone. When he stood up, he noticed a small skeleton. It took some convincing, but eventually, the boys’ parents decided to have a look at the dinosaur their sons had claimed to have discovered. Upon arrival, the adults decided the twisty creature had some possibility and hacked it out, keeping the fossil intact within a large piece of stone. Even though no dinosaur had ever been found at Cape Egmont (western Prince Edward Island beach), Arsenault believed that it was. When a museum curator saw the fossil, he told the boy that it was not a dinosaur. It was something better. The extraordinary skeleton belonged to the only reptile unearthed from the five-million-year Gzhelian Age. At 250–300 million years old, the creature was older than the dinosaurs. Arsenault kept it in his bedroom until 2004, when he sold it to the Royal Ontario Museum. Officials analyzed it properly this time and announced that it was a new species, Erpetonyx arsenaultorum. The lizard is a priceless piece from early reptile evolution, a time that has produced very few fossils so far.[8]

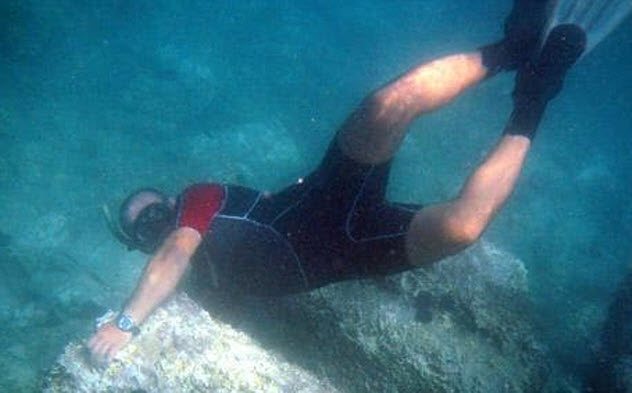

2 Submerged Temple

In 2009, 16-year-old Michael Le Quesne vacationed with his family at Maljevik, a small bay on the Montenegrin coast. One day, he was snorkeling in shallow water when rocks caught his eye. They looked natural but somewhat cylindrical. Any other person might have swum off. But Le Quesne was the offspring of a professional archaeologist father. As such, he had seen more ruins than the average kid. He fetched his dad. Charles Le Quesne’s trained eye soon identified a huge building on the seafloor. It resembled important buildings from other ancient Mediterranean sites. Thick fluted pillars, either Greek or Roman, suggested a temple or basilica. More ruins nearby make it likely that the building was the main structure of an important trading post. There are no historical records of a settlement in the area, but local shipwrecks support the belief that the new ruins belonged to a port. The untouched “temple” dates to the second century BC and could have disappeared into the sea after an earthquake. But its true purpose and history remain a mystery.[9]

1 The Faggiano House

The house in question is modern and ordinary. However, it sits on a cake layer of history from nearly every civilization that called Lecce, Italy, home. In 2000, Luciano Faggiano followed his dream of owning a small restaurant and purchased the building. The toilet needed fixing. Faggiano thought it would take about a week to dig open the troublesome plumbing. Instead of the pipe, he found a false floor. Once removed, Faggiano and his family spend years excavating an extraordinary space. Rather than run a restaurant, they explored rooms and corridors from a world before Jesus. Finds included a Roman granary, a Messapian tomb, and a Franciscan chapel where nuns prepared corpses for burial. Most remarkably, they found etchings from the Knights Templar. Frescoes, medieval items, vases, Roman devotional bottles, and a ring with Christian symbols turned up. The seemingly endless discoveries (artifacts are still being found) could spring from Lecce’s past. The exceptionally ancient land was settled by many major civilizations such as the Greeks, Romans, and Ottomans. Now the building is the Museum Faggiano. Spiral stairwells guide visitors down to levels that represent nearly every phase of the city’s history.[10] Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages