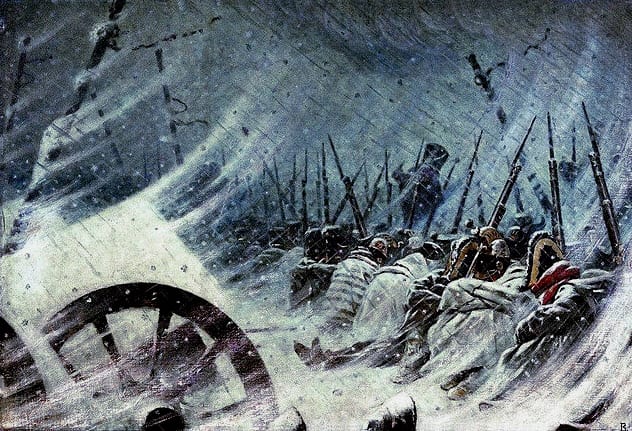

10 Napoleon’s Retreat From MoscowRussian Campaign

Determined to convince Tsar Alexander I to stop sending the United Kingdom raw materials which enabled them to continue the war effort against France, Napoleon decided to invade Russia, a decision which haunted him for the rest of his life. After he and his Grande Armee finally arrived in Moscow on September 14, 1812, Napoleon was disheartened to see that the Russian military, as well as the civilian population, had fled the city. Although Napoleon expected to find supplies to aid his increasingly demoralized army, he found nothing. After only a month of waiting for a surrender that never came, Napoleon decided to retreat,[1] leaving the city and hoping to escape the harsh Russian winter which was on its way. However, hunger proved to be as much of an enemy as the Cossacks, who constantly tormented the Grande Armee as it slowly marched westward. In addition, wolves trailed Napoleon’s men wherever they went, picking off stragglers as far as the Rhine. (Some say this is why the forests of Central Europe are home to the number of wolves that they have to this day.) In all, of the more than 500,000 soldiers who went into Russia, fewer than 100,000 ever made it out.

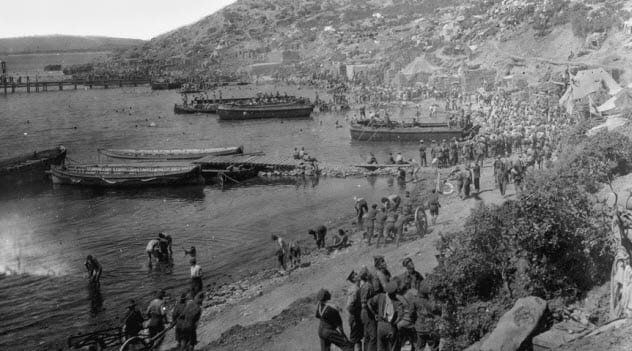

9 The Allied Evacuation Of GallipoliWorld War I

Though he later disavowed the debacle that ensued, the future British prime minister Winston Churchill was one of the architects behind the World War I operation known as the Gallipoli Campaign. Originally designed to be a largely sea-based invasion, bad weather and subsequent losses due to mines prompted the war planners to decide that a land-based invasion would work better. However, the Allied forces sustained heavy losses, barely making it more than a few miles inland. Eventually, after being bogged down just as they were on the Western Front, evacuation orders were drawn up. More or less the only thing that went right for the Allied troops during the campaign, most of those still alive were evacuated to safety. Just before the last of the Australians left, Padre Walter Dexter walked through the cemeteries, scattering silver wattle seed and saying: “If we have to leave here, I intend that a bit of Australia shall be here.”[2] One of the reasons they were able to escape relatively unscathed was the work of an Australian named William Scurry. He rigged up a self-firing rifle contraption which convinced the Turkish fighters that they were still being shot at by soldiers after everyone had already begun to leave.

8 Highway Of DeathGulf War I

After years of economic struggles (which were due to Kuwait and its policies in his mind), Saddam Hussein began the invasion of his neighbor on August 2, 1990. Uniformly condemned by nearly every other nation, the hostilities were quickly (in international terms) met with ultimatums, including the United States’ proclamation that Iraq had to withdraw its forces by January 15, 1991. Iraq refused. Shortly afterward, Operation Desert Storm began. Thoughts of retreat began to enter the minds of many Iraqi soldiers as they were overwhelmed by coalition forces. The main highway out of Kuwait City was their most likely escape route, which coalition forces quickly realized as well. On the morning of February 26, 1991, more than 1,500 Iraqi vehicles began their trek out of Kuwait. Unfortunately for the Iraqis, they were “basically just sitting ducks” in the words of Commander Frank Sweigart. A cavalcade of bombs tore through the ranks, with subsequent fires engulfing many of the vehicles. (Those fires resulted in one of the more infamous photographs[3] of the war.) Though the retreat may seem to have been unsuccessful, as many as 80,000 troops are estimated to have successfully withdrawn according to the US Defense Intelligence Agency.

7 George Washington’s Escape From New YorkAmerican Revolutionary War

In 1776, the Battle of Long Island, the first large-scale battle which occurred after the United States declared its independence, saw George Washington face off against William Howe. Washington had surmised that the capture of New York would be one of Britain’s goals, and his 19,000 soldiers were moved to Lower Manhattan. Stationed on nearby Staten Island, Howe planned to use his warships to block the river while his soldiers marched on the Americans over land. Howe’s plan met with instant success,[4] partially due to his overwhelming numbers advantage. (He had around 32,000 men.) However, he paused after the first few days of fighting, intending to prepare for a final push. Washington took advantage of this delay—as well as a fortuitous storm that drove British warships from the area—and he ordered a retreat of his men. In the end, 10,000 Americans took part in the fighting, with 8,000 of them escaping. This enabled Washington to snatch a stalemate from the jaws of defeat. Legend has it that a fog descended on the retreating Americans, with Washington said to be the last to leave.

6 Russian Retreats Against NapoleonRussian Campaign

By 1812, Napoleon had earned a reputation as an incredible general, one whose lightning speed (for the age) confounded his opponents. Many of his adversaries were used to smaller-scale, more methodical forms of fighting. After Tsar Alexander I decided to ignore the terms of the Treaty of Tilsit and begin trading with England, Napoleon decided enough was enough, with all-out war his only option. So he and his Grande Armee marched on Russia. However, Russia’s leaders were no fools. They knew that the best plan was one used by Wellington: systematic retreats[5] which would draw the French into a slow, drawn-out campaign and nullify one of their biggest advantages. Napoleon’s fighting forces often lived off the land to supplement their supply trains. So the Russians instituted a scorched-earth policy, denying their enemies anything of use. (It also did irreparable harm to Russian citizens who were living in the area.) However, Russia’s strategy proved invaluable in war. It slowly drained Napoleon of almost all his fighting men before he stumbled into Moscow.

5 The Great RetreatWorld War I

In 1914, the Battle of Mons was the first taste of the new age of warfare for the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), which came to the aid of the French Fifth Army as the Germans attempted to outflank them in World War I. Badly outnumbered by nearly two to one, the BEF nevertheless persisted. They were intent on inflicting as much damage on the Germans while keeping them from overrunning the BEF’s position. On the morning of August 23, 1914, the BEF got the chance to test their mettle as enemy artillery began to pound their line. British rifle fire was so quick and accurate that the advancing Germans were certain they were facing lines of machine guns. While the “Old Contemptibles” managed to hold their own, the French Fifth Army did not fare so well, leading their commander to order a retreat[6] early on August 24. The British had no choice but to retreat as well. They began what has come to be known as the Great Retreat, a two-week march to the Marne River. Eventually, through a number of rearguard actions, the Allies reached the river. They turned around, halting the German advance and forcing a brief retreat of their forces in the Battle of the Marne. This bought time for an even more unlikely “victory” for the British later.

4 Mao Tse–Tung’s Long MarchChinese Civil War

The Red Army of the Communist Party of China was on its last leg, hounded into extinction by the Kuomintang Army, a rival force fighting for control of the country. On October 16, 1934, the leaders of the Red Army decided that a retreat was the only option. The 86,000 troops were surrounded in the Jiangxi province and, through subterfuge, managed to break out to the west to begin their escape. Their goal was the northwestern province of Shaanxi, a place which would allow them to heal in isolation. Unfortunately for them, it didn’t take long for their enemy to notice the retreat had begun. Aerial bombardment and ground fighting whittled down the Red Army to half its original size. By January 1935, Mao Tse–tung had managed to garner enough support to take control of the army. Though his ascent helped with the problem of lagging morale, it didn’t do much to change the army’s fortunes. People just kept dying. By the time they reached Shaanxi in October 1935, only 8,000 troops remained.[7] Though the retreat can’t be seen as a military success, the 6,400-kilometer (4,000 mi) journey did become a legend among the youth of China. This inspired many of them to join the Communists over the next decade.

3 Battle Of Chosin ReservoirKorean War

In late November 1950, the Chinese Ninth Army began an overwhelming surprise attack on United Nations troops stationed at the Chosin Reservoir in eastern North Korea. In all, 150,000 Chinese troops were directed by Mao Tse-tung to encircle and annihilate the 30,000 men they faced. Initially successful in their attacks, the Chinese failed to complete the encirclement, allowing the United Nations forces to escape to the south in what proved to be an arduous journey for all involved. Narrow mountain roads slowed the Americans and their allies, with the 1st Marine Division of the United States performing some of the most storied actions in the history of the Marine Corps.[8] For over two weeks, the retreat continued, with both sides inflicting casualty after casualty upon one another. By the time the United Nations troops reached the safety of South Korea, nearly 18,000 of their men were dead, wounded, or missing. However, it was very much a Pyrrhic victory for the Chinese, who lost twice those numbers. The astonishing number of deaths, especially among their elite troops, forced the Chinese to delay any more attacks, perhaps saving South Korea from being captured. The most famous quote from this battle was uttered by General Oliver P. Smith, who said: “Retreat, hell! We’re not retreating, we’re just advancing in a different direction.”

2 Battle Of DunkirkWorld War II

In May 1940, the German blitzkrieg was tearing through Continental Europe like a plague. Poland, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg. All these countries had been conquered or would be soon by the might of the Nazis. France was soon to follow, and it’s there that this story picks up. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) had joined forces with the French army, determined to keep the Germans out of the country. However, the speed and devastating skill of their foes soon proved to be too much as the Nazis quickly stormed through the French countryside. The Germans were seemingly on the verge of taking the city of Dunkirk, the last port which could be used to evacuate the more than 300,000 Allied troops stationed there. In a stroke of luck for the Allies, Hitler ordered his men to halt on May 24.[9] Hermann Goering, the leader of the Luftwaffe, had assured Hitler that the aircraft under Goering’s command could finish the job. Though the delay only amounted to a few days, the Allies were able to fortify their defenses enough to allow nearly everyone to escape. In fact, many of the boats which helped secure passage back to Britain were privately owned: fishing boats, yachts, and lifeboats.

1 The March Of The Ten ThousandBattle Of Cunaxa

Immortalized by the ancient Greek historian Xenophon in his work Anabasis, the March of the Ten Thousand is the story of a group of Greek mercenaries who went to war in Persia. They were hired by Cyrus the Younger, who planned to go to war with his brother Artaxerxes II and seize the throne. However, Cyrus was slain in battle, stranding the Greeks in enemy territory with no one to guide them out. More than 2,700 kilometers (1,700 mi) from the sea, the Greeks were asked to surrender, a death sentence to be sure, and they refused. The Greeks were harried by the Persians for the entire journey to the Black Sea, but local tribes and the elements proved to be deadly foes as well. After suffering through a snowstorm which thinned their numbers, the Greeks arrived at a town named Gymnias. They didn’t wait there long because a local guide assured them that they were only five days from the sea. Five days later, Xenophon began hearing cries from the men at the front of the line. Fearing an attack, he rushed to the front, only to realize what the men were screaming: “The Sea, The Sea.”[10] Though some of them died on the journey, most managed to arrive safely in Greece.