Far from being unintelligent farmers, people during medieval times had complex behaviors, mysteries, and very relatable problems. But perhaps the most magnetic quality about them is that tiny, alien part the modern mind will always be amazed by. Simple things whipped up deadly frenzies, and their approach to marriage and parenting is almost unrecognizable today.

10 They Rearranged Graves

In medieval Europe, a massive 40 percent of graves were disturbed.[1] In the past, unsavory robbers were solely blamed. However, two cemeteries recently revealed it may have been a community thing. The Austrian cemetery Brunn am Gebirge contained 42 graves from the Langobards, a sixth-century Germanic tribe. All but one had been rummaged through, and only certain objects were taken. There was also a noticeable way in which the remains were treated: Skulls were removed, or an extra one was added. Most bones were moved with some sort of tool. The motive is unclear, but the tribe might have been trying to prevent the undead from rising. It is also possible the Langobards wanted reminders of their lost loved ones. This could be why over a third of the skulls were missing. In an English graveyard, Winnall II (seventh and eighth centuries), skeletons were bound, decapitated, had twisted joints, and contained bones from other individuals. Originally, they were thought to have been given strange funerals. There is growing evidence, however, that the manhandling happened later, perhaps because locals believed the restless souls brought bad luck.

9 Marriage Was Difficult To Prove

Getting married in medieval England was easier than tripping over a log. All that were needed was a man and a woman, and each had to verbally agree to the union.[2] If the girl was 12 and the boy 14, no family consent was necessary. No church or priest came into play. People often tied the knot wherever they were, be it down at the local pub or in bed. (Sex counted as automatic marriage.) A church warning echoed one of the dangers of such glib matrimony. It cautioned young men not to abuse it just to fool girls into having sex. Most couple-related cases before the court were indeed to prove that a wedding had happened and to enforce it. If couples married alone, it was extremely hard to say what was agreed to (or wrongly assumed). For this reason, vows were encouraged to be taken in the presence of a priest. Divorce could only happen if the union was never legal in the first place. Reasons included still being married to a previous partner, being related (distant ancestors were often invented), or being married to a non-Christian.

8 Men Received Infertility Treatment

In the ancient world, the usual approach to a childless marriage was to eye the wife with suspicion. This was also assumed to be the case in medieval England. But researchers found the opposite to be true. From the 13th century, men were also held accountable, as medical books of the time discussed male reproductive problems and sterility.[3] The pages also contain some odd advice to identify the infertile partner and what treatment to employ: Both had to pee in separate pots full of bran, seal them for nine days, and then check for worms—the smoking gun. If the husband was believed to be the one who needed treatment, he faced hairy options to treat his “unsuitable seed.” To cure conception difficulties in any person, one recipe called for dried pig testicles to be ground up and consumed for three days with wine. Though physicians accepted infertility as a medical condition, medieval courts were less forgiving. A wife could divorce her husband if he was impotent.

7 Apprentices Caused Trouble

In Northern Europe, parents had the habit of booting teens from the house and into an apprenticeship that often lasted a decade.[4] The benefits for the adults included one less mouth to feed, and the master got cheap labor. Surviving letters, written by the teens, show the experience was traumatic. Some historians feel the youngsters were sent off because they were unruly and that their parents believed training would have a positive impact. Perhaps the master craftsmen knew trouble when they saw it because many had their students sign a contract to behave. Even so, apprentices got a bad name. Being away from their families, resenting their lives of labor, and bonding with fellow ticked-off teens soon produced gangs. At their most tame, they gambled and frequented brothels. In Germany, France, and Switzerland, they gatecrashed carnivals, caused disorder, and once held a town to ransom. In London’s streets, violent fights broke out between different guilds, and in 1517, they looted the city. It is likely that the hooliganism came from disillusionment. Despite all the years invested, many understood that it was no guarantee of future work.

6 The Real Medieval Elderly

In early medieval England, a person was considered elderly by age 50.[5] British scholars hailed the era as a “golden age” for people of advanced age. It was believed that society revered them for their wisdom and experience. This was not entirely true. Apparently, there was no concept of letting somebody enjoy their retirement; the older folks had to prove their worth. In exchange for respect, society expected older members to continue to contribute—especially warriors, holy men, and leaders. Soldiers still fought, and workers still worked. Medieval authors had mixed emotions about growing old. Some agreed that the elderly were spiritually superior, while others belittled them as “hundred-year-old children.” Old age itself did not receive pretty poems. Text described it as a “foretaste of hell.” Another misconception is that everybody keeled over before getting truly old. Some people still lived well into their eighties and nineties.

5 Everyday Deaths

During the Middle Ages, not everybody perished from spectacular violence and warfare. Citizens also died from domestic violence, accidents, and too much fun.[6] In 2015, researchers perused the medieval coroners’ records of Warwickshire, London, and Bedfordshire. The results offered a unique look at daily life and hazards in these counties. Death by pig was a real thing. In 1322, two-month-old Johanna de Irlaunde died in her crib after a sow bit her in the head. Another pig killed a man in 1394. Cows also were responsible for several fatalities. According to the coroners, drowning accounted for the biggest number of accidental deaths. People succumbed in ditches, wells, and rivers. Murder is to be expected. One graphic story from 1276 details how Joan Clarice cut her husband’s throat and literally beat his brains out. Several died from disputes, but falling also culled quite a number. People toppled from trees, buildings, and too much drink, and one woman fell off a chair she used to reach a candle. In 1366, John Cook wrestled a friend for fun but died the next day from his injuries.

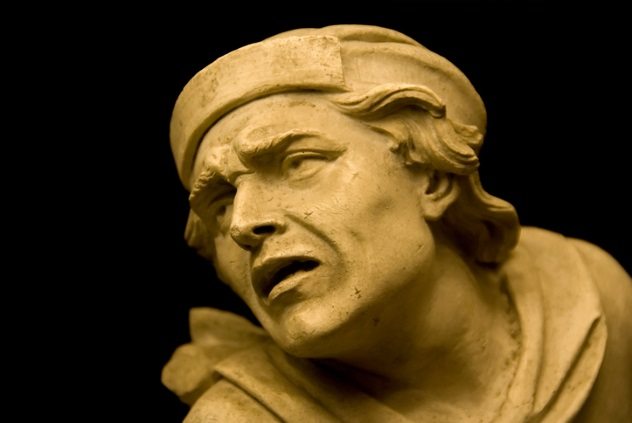

4 Londoners Had It The Worst

To put a finer focus on the bloodshed, one did not truly want to move the family to London. It was the most violent spot in England.[7] Archaeologists pondered over 399 skulls, dating from 1050 to 1550, from six London graveyards across all classes. Nearly seven percent showed suspicious physical trauma. Among these, lower-class men aged 26 to 35 filled the most graves. With violence rates double that of anywhere else in the country, the cemeteries showed that working-class males faced extreme aggression. Once again, the coroner’s roll gave some insight. An unnatural number of homicides happened on Sunday evenings, a time when most lower-class men were in taverns. It is likely that drunken arguments happened frequently, with fatal results. In addition, only higher classes could afford a barrister or partake in duels where both parties had protection. The rest had to settle disputes and revenge with deadly informal fights.

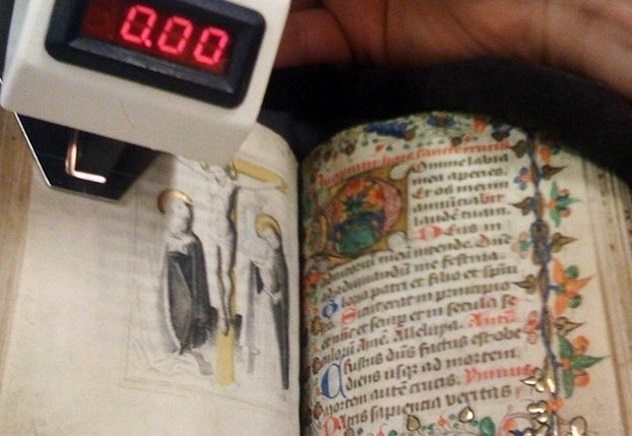

3 Medieval Reading Habits

During the 15th and 16th centuries, religion was immersed in every part of people’s lives. Prayer books, in particular, were popular.[8] Using a technique that calculates shades on a surface, art historians realized something: The dirtier the page, the more readers were drawn to the content. To understand what their reading habits were as well as possible reasons behind it, several prayer books were scanned. The most thumbed pages showed medieval Europeans were not that different. One manuscript held a prayer dedicated to St. Sebastian, said to be able to ward off the plague. The prayer was constantly touched, likely by someone who dreaded getting sick. Other prayers about personal salvation also received more attention than those asking the same for another person. These prayer books were treasured and read daily. However, a humorous find involved one particular prayer. The long piece was always read very early in the morning. Since only the first pages were smudged, it would appear the verse put most people back to sleep.

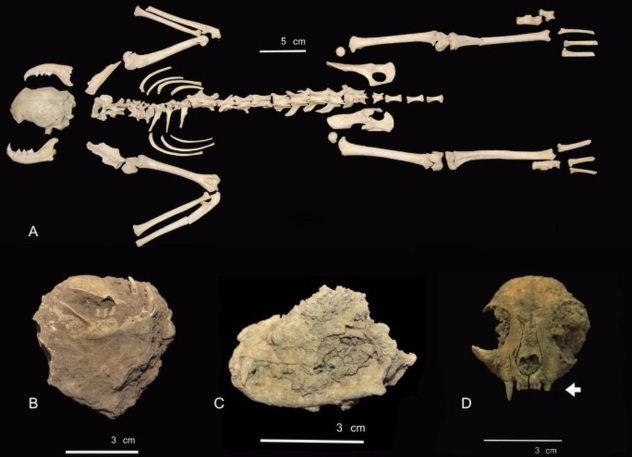

2 They Skinned Cats

In 2017, a study found that the cat fur industry also extended to Spain. This medieval practice was widespread and used both domestic and wild cats.[9] El Bordellet was a farming community 1,000 years ago. Among its many medieval finds are pits thought to have stored crops. But some of them held animal bones, and an unexpected number, around 900, belonged to cat skeletons. They were all in the same pit. Bone growth indicated they were nine to 20 months old, the best age to yield a large, unblemished pelt. Another strong indication that the felines were skinned were cut marks. They marred the remains at the right angles, intensity, and number. It may make pet lovers cringe, but Northern Europe already slaughtered felines as clothes trimming or to make cat coats. However, researchers believe the El Bordellet cats could have served another purpose—as an ingredient in a ritual. Their pit included a horse skull, chicken egg, and goat horn. All three are known additions to magical medieval rites.

1 Wearing Stripes Was Deadly

Stripes make a chic fashion turn every few years, but back in the day, a lined outfit could get a person killed. In 1310, a French cobbler decided to wear striped clothing for the day. He was condemned to death for his decision. The man was part of the town’s clergy, which did not sit well with the belief that stripes belonged to the Devil. Good citizens, too, had to avoid wearing bands at all costs. Prolific documentation from the 12th and 13th centuries reveals the strict stance authorities took against the pattern. It was considered the dress of society’s most tarnished—prostitutes, hangmen, lepers, heretics, and, for some reason, clowns. Even the disabled, bastard children, Jews, and Africans were slapped with stripes.[10] It is a mystery how the hatred became so easily entrenched. Why not spots or squares? No theory can adequately explain the link between Satan and stripes. One speculative grab cites a Bible verse: “You will not wear upon yourself a garment that is made of two.” Perhaps the medieval mind interpreted the passage as a reference to stripes. Whatever the reason, by the 18th century, the strange aversion was over. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages