For decades afterward, Sherpas served as porters for climbers going up the mountain. A habit of overlooking the locals (and plenty of misconceptions) followed. A pity, really, because this culture from Nepal is fascinating. Sherpas are driven. They win awards from National Geographic and set some of the best climbing records out there. They also have unique genetics, which boosts their excellence as mountaineers. But the risks of the trade are overwhelming. On Everest, Sherpas die more than anyone else. 10 Tribes With Superpowers You Wish You Had

10 ‘Sherpa’ Does Not Mean ‘Mountain Guide’

After Edmund Hillary, the media started the misconception that “Sherpas” describes local guides. In reality, the word means “Easterners.” Indeed, the majority are settled in eastern Nepal, home to Mount Everest. The Sherpas are also an ancient ethnic group whose ancestors have lived in the region for thousands of years. A 2011 census counted almost 313,000 Sherpas in Nepal. Curiously, they were not always famous mountaineers. Before foreigners started climbing Everest, Sherpas never scaled the cliffs. The mountain was a holy place, something that still reflects in the local name today. Jomolungma means “Sacred Mother.” Sherpas made their living as farmers, nomadic cattle herders, and weavers. They also traded in the now-famous pink Himalayan salt. However, during the early 1900s, the Sherpas tasted a decent income as guides and they were hooked. The blasphemy of climbing Jomolungma was replaced with being proud of their skills and providing more for their families.[1]

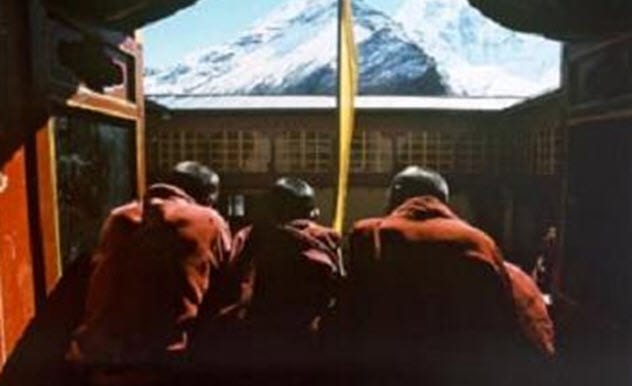

9 Sherpas Follow An Ancient Branch Of Buddhism

Sherpas borrowed their spiritual beliefs from the Tibetans. Sherpas no longer know when this happened, but the branch they chose is ancient. The Nyingmapa school of Tibetan Buddhism dates to the eighth century when Buddhism arrived in Tibet. Around 1850, several Sherpa priests arrived in Tibet to study with a great master, Trakar Choki Wangchuk. They returned with new rituals and the lifestyle that marks Sherpa Buddhism today. Nyingmapa added beauty and learning to their culture. Many rituals are joyful and accompanied by chanting. They have monks. Studying the Tibetan language also spread literacy and the skills that went with it—paper and ink production, calligraphy, and woodblock printing.[2] The latter is used to create books, and Sherpa printers started with rough equipment. Pure dedication improved their carving techniques until their sophistication rivaled that of Tibet.

8 They Pick Up Trash And Bodies

Mount Everest offers breathtaking views and crisp nature scenes. But when climbers look down and around their feet, they see something else entirely. The ground is littered with trash, broken equipment, and human excrement. Over the years, 300 people have died on the slopes, so the chance of finding a body is always in the cards. The situation is embarrassing for the Nepalese government, which relies heavily on the revenue generated by climbing permits. Every now and then, a cleanup effort gets underway. The 2019 sweep employed 20 Sherpas to collect trash and take the bags to a recycling plant. From just a few campsites, they gathered 11 tons during April and May. That year was also one of the deadliest seasons, killing 11 mountaineers in different incidents. When the Sherpas came across four bodies, it was no surprise. However, nobody knows who the deceased were or when they died. The only certain thing is that the melting snow exposed two of the bodies at the lethal Khumbu Icefall and the rest at a campsite at the Western Cwm. The cleanup crew brought the corpses down along with the rubbish.[3]

7 The Record For Most Summits Belong To A Sherpa

In mountaineering lingo, “summiting” means reaching the peak. For most climbers, Mount Everest is a one-time deal. It involves planning, training, thousands of dollars, and good luck. After summiting, they go home and brag about standing atop the world’s highest mountain. In 2019, a guide called Kami Rita Sherpa reached the top for the 24th time. Not only was this the world record but also Kami’s second summit in a week.[4] Kami’s father and older brother were both guides and taught him the trade. His career started in 1993, and by the time he set the record, he was 49 years old. He recently told the BBC that he has no intention of retiring.

6 Sherpa Women’s Records And Awards

Traditionally, the men work as guides. But that does not stop the ladies from being porters, scaling Mount Everest, or having other adventures. While many Sherpa women are breaking new ground, two deserve special mention. Lhakpa Sherpa holds the record for the most successful summits for a female climber. She has made it to the top nine times, all while raising three children, dealing with an abusive husband, and holding two jobs in the United States. National Geographic also awarded a Sherpa woman with their 2016 Adventurer of the Year award. When she was 15, Pasang Lhamu Sherpa Akita lost her parents and took up mountaineering to support her six-year-old sister. By the time she won the award at age 31, she was a seasoned climber of the world’s tallest peaks.[5] But Pasang is also a humanitarian. Months before she was announced as the winner, an earthquake hit Nepal. During the hardship that followed, the Nepali found pride and comfort in Pasang’s international award and her tireless efforts to bring aid to the victims. 10 Harrowing Stories Of Life And Death On Mount Everest

5 They Have A Genetic Superiority

When explorers first employed Sherpas, a difference quickly surfaced. The thin air of the high altitudes made the visitors tired or sick. Some died. But the guides continued to function efficiently and without fatigue. In 2017, this edge showed up in an interesting way. Kilian Jornet, an elite ultrarunner, raced toward Mount Everest’s peak without ropes or extra oxygen. Most climbers need four days and bottles of oxygen to accomplish this feat. Jornet clocked an incredible 26 hours. Hand that man a silver medal. Years earlier, a man called Kazi Sherpa had made it in 20 hours. In 2017, researchers also discovered that natural selection was behind Sherpa perkiness in low-oxygen environments. For thousands of years, this mountain community lived with little oxygen. Instead of turning blue and tired, their bodies adjusted in remarkable ways.[6] To produce energy, the body normally burns fat. But this process needs a lot of oxygen. The efficient Sherpas burn sugar, a low-oxygen alternative. Foreign climbers also deplete phosphocreatine, a compound that supports muscle strength. Phosphocreatine in Sherpas either spikes or stays level, but it rarely drops.

4 The Lhotse Face Incident

The general view is that Sherpas never get angry. However, in 2013, a group of Sherpas not only lost their cool but also allegedly tried to murder foreigners on Mount Everest. Simone Moro, a world-renowned alpinist, was busy with his fifth trek up the mountain when his group encountered Sherpas on the Lhotse Face. What sparked the scuffle remains unclear. But the guides were fixing ropes, which provide climbers with more stability. Moro and his two friends were experienced enough not to need the ropes, so nobody bothered the Sherpas while they were working. Apparently, the guides told the climbers to go home. When they refused, the Sherpas pelted them with ice. There was some yelling from both sides. At one point, everybody climbed down. Moro claimed that his team first fixed some of the rope to show goodwill. But when they reached camp and radioed this news to the Sherpas, a group of 100 showed up. Instead of gratitude, a few tried to kill the three men. One of Moro’s companions was hit in the face with a rock. Moro was kicked, punched, and stoned.[7] During a National Geographic interview, Moro said that he had “feared for his life” and that a woman had helped them. Melissa Arnot, another famous alpinist, physically shielded the three men, hoping that the Sherpas would not hit a woman. They yelled at Arnot but never harmed her. A Sherpa man also pleaded for the violence to stop. After nearly an hour, the attack ended. Later, Moro returned and made peace with the group. He did not get punched at that time.

3 They Want Other Jobs For Their Children

Most guides work on Everest because they learned the trade from family. They often do not have the education to do anything else. Even though some of them prefer safer work, being a guide is one of the highest-paying positions in Nepal. It gets them out of poverty and provides the means to educate their children so that the next generation can break the cycle. Another reason why Sherpas want their children to choose a different career is how foreigners treat them. Most Westerners cannot summit on their own. They need Sherpa expertise to make it to the top. Too many visitors are terrible climbers, and the guides have their hands full to keep the expedition safe. Worse, after some clients succeed and tell the story, they never acknowledge the hard work and risks that only the Sherpas endured.[8]

2 Their Work Is Deadlier Than Warfare

That is a bold statement. After all, combat includes flying bullets and violence. Sherpas carry loads and prepare the way ahead for their clients. Nobody shoots at them. But nature is a dangerous creature on a mountain. Anyone can perish in storms, avalanches, and falls. The plight of Sherpas was revealed when Outside magazine tried to find the world’s most dangerous careers. The analysis counted the number of deaths per 100,000 employees. Miners averaged 25 deaths, US soldiers in Iraq numbered 335, and Everest guides clocked a chilling 1,332 deaths.[9] However, 1,000 Sherpas never tumbled to their deaths. The actual number is around 94. Some magnification occurred in an absolute sense because the study could not look at 100,000 employees when computing the Sherpa death rate. As of 2018, the 94 represents one-third of Everest’s fatalities. This death rate makes being a Sherpa guide one of the deadliest jobs in the world.

1 13 Died During Everest’s Worst Disaster

Around 300 climbers follow the Southeast Ridge route every year. The pathway has pedigree—it was pioneered by Sir Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay. Along the way is a spot called the “popcorn field.” Named for the massive blocks of ice, this is one of the deadliest places on Everest. Some climbers feel it’s the most lethal place in the world for their sport. The field is like a highway for avalanches. During the day, they occur with frightening frequency. Those who wish to cross must do so at night when the ice is more stable. In 2014, tragedy struck. An avalanche caught porters inside the popcorn field. There was nowhere to run or hide. When the snow ground to a halt, 13 Sherpas were dead. The event was the worst day in the history of Everest mountaineering.[10] 10 Creepy Tales About Well-Known Mountains Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages