The London of 1666 consisted largely of houses constructed from oak timbers, which were covered in flammable tar in order to keep out the rain. The houses were crammed together in narrow streets, where the only real firefighters were neighborhood teams of “bucket brigades” whose only tools of the trade were leather water pails and primitive hand-operated water pumps. The Great Fire of London was said by many at the time to be an event of inevitability, and London’s citizens had been ordered to check their homes for possible fire risks. Here are ten incredibly bizarre facts that surround the Great Fire of London.

10It Was the Second Major Catastrophe to Hit the City within Twelve Months

The Great Fire of London began just as the city was starting to recover and rebuild itself from the horrendous effects of The Great Plague of London. Just a year earlier, the city had tragically lost an estimated 100,000 people (almost a quarter of its population) from an outbreak of bubonic plague, which at its peak was claiming as many as 8000 victims a week. The Great Plague of 1665, originally caused by the Yersinia pestis bacterium, usually transmitted through the bites of infected rat fleas, was thankfully the last widespread outbreak of bubonic plague in England. It was not until February 1666 that the city was once again considered to be adequately safe for the return of King Charles II and his entourage.

9The Food-Themed Fire Was Started in Pudding Lane by the King’s Baker and Ended at Pie Corner

After a hard day’s work, the King’s baker, Thomas Farriner, raked up the coals in the bakery hearth and went up to bed above his Pudding Lane bakery shortly before midnight on the evening of Saturday, September 1, 1666. The coals reignited a short time later, and the Great Fire had started. Farriner, his daughter Hanna, and a manservant all luckily managed to escape into a neighbor’s home from an upstairs window. The maid, whose name is still unknown was sadly unable to escape from the burning building and perished in the flames, becoming the Great Fire’s first victim. The fire was finally brought to a halt four days later on Wednesday, September 6, at the corner of Cock Lane and Giltspur Street, known as Pye (or Pie) Corner. A small gilded statue of a child, known as The Golden Boy of Pye Corner still stands at the site as a memorial to The Great Fire of London, and bears the following inscription, “This Boy is in Memory put up for the late Fire of London Occasion’d by the Sin of Gluttony.”

8The Lord Mayor of London Refused to Take the Fire Seriously

In the early hours of September 2, just as the fire was beginning to take hold, London’s Lord Mayor, Thomas Bloodworth, arrived at the scene of the bakery in Pudding Lane. On the grounds of costs, he defiantly refused to allow the demolition of the adjoining buildings, which would have almost certainly kept the fire contained. Lord Mayor Bloodworth, in his view of the fire’s insignificance, impatiently, and now infamously, declared that “A woman might piss it out!” He turned on his heels, returned home to the comfort and safety of his bed and left the city to its fate. In view of his behavior and attitude, he has been wholeheartedly criticized and widely blamed for the extent of the damage caused to the city.

7It Was Not the First Great Fire of London

Whilst undoubtedly the best known and most damaging fire in London’s long history, the Great Fire of 1666 was by no means the first. The city of London’s history is peppered with tales of notable fires through the ages. Boudica and the Iceni are known to have razed the city to the ground in as far back as the year A.D. 60. Notable fires also occurred in the years 675, 989, 1087, 1135 (which famously destroyed London Bridge), and the 1212 Great Fire of Southwark, which was said by John Stow in his 1603 account to have killed as many as 3000 people, although this figure is now sometimes disputed by historians.

6Samuel Pepys Buried Cheese in His Garden before Fleeing from the Path of the Fire

We all owe a huge debt of thanks to Samuel Pepys and his fastidious diary-keeping. He kept a detailed daily account of his life throughout the 1660s. His personal diaries were first published in 1825 and have become one of the most important eyewitness accounts and primary sources for both The Great Plague and The Great Fire of London. Living in the path of the fire’s spread, Pepys, along with hundreds of others, began arranging the removal of his most valuable possessions by cart and river barge to ensure their safety. One of his most cherished possessions was a wheel of Italian Parmesan cheese, much prized amongst the noble classes at the time and highly expensive. His diary entry for Tuesday, September 4, 1666, records how he dug a pit in his garden in which he buried his wine along with his cheese for safekeeping. The subsequent fate of the cheese is not known.

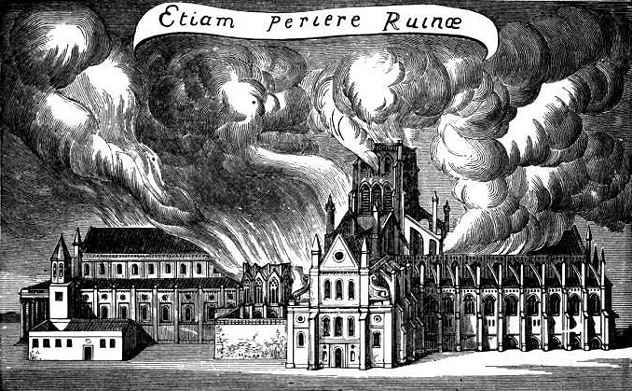

5The Fire Definitely Did Completely Destroy St Paul’s Cathedral

It has often been thought that the religious heart of the city, St. Paul’s Cathedral, survived the Great Fire of London completely intact. This is simply not true. While the domed London landmark did indeed survive the German aerial bombings of World War II in the 1940s, the medieval cathedral built in 1240 was completely destroyed by The Great Fire of London on Tuesday, September 3, 1666. Ironically, the architect Sir Christopher Wren had attended a meeting at the cathedral to discuss an ongoing program of its repairs and restoration on August 27, 1666—just eight days later, the building was razed to the ground after the flames began to lick at the cathedral’s timber scaffolding. With its five-foot (1.5 m) thick stone walls and empty surrounding plaza, the cathedral was seen by many as a safe place of refuge from the fire. The cathedral’s crypts had been filled with papers and books for safekeeping, only to provide further fuel for the fire. One week after the fire, the books were still burning. By 8:00 p.m., the flames had spread to the roof which measured a huge six acres (2.4 hectares). Covered in lead, this quickly began to melt, and just 30 minutes later, the molten lead was cascading into the cathedral’s nave, onto the surrounding streets, and down Ludgate Hill like volcanic lava. The diarist John Evelyn wrote at the time, “the melting lead running down the streets, and the very pavements glowing with fiery redness, so as no horse, nor man, was able to tread on them.” As well as being tasked to design the replacement cathedral, Sir Christopher Wren also designed “The Monument,” built to commemorate the fire. It stands an impressive 202 feet (62 m) tall—the exact distance between its base and the site of the fire’s start in Pudding Lane.

4The Fire Had an Unbelievably Low Death Toll

The extent of the material damage caused by the fire was truly astounding. The fire consumed 85 percent of the city, an area measuring one by 1.5 miles (1.6 by 2.4 km). Eighty-seven parish churches and at least 13,200 homes were completely destroyed, leading to more than 100,000 people evacuating the city southwards across the River Thames and northwards to Clerkenwell, Finsbury, and Islington. The 1673 census revealed that 25 percent of these people did not return to the city. Despite the horrendous scale of the damage caused to London, just six deaths were (officially) recorded. Incredibly, more people than this have been killed by falling from the top of The Monument erected to commemorate the fire. The actual death toll, though, is thought to have been much higher, as deaths amongst the poor classes were not recorded. In any case, human remains would not have survived the ferocity of the fire, which reached temperatures of 3000 degrees Fahrenheit (1650 degrees Celsius)—high enough to melt stone.

3An Innocent Man Was Hanged for Starting the Fire

Robert Hubert was a simple-minded French watchmaker in his mid-twenties who claimed to be a French spy and an agent of the Pope. He confessed to starting the fire in Westminster, despite the fact that the fire never actually reached this part of London. When it was brought to his attention that the fire started at the Thomas Farriner’s bakery in Pudding Lane, he then claimed to have thrown a homemade fire grenade through an open window. It later emerged that Hubert was not even in the country at the time of the fire’s outbreak, he was on board a Swedish ship and did not arrive ashore in the UK until the fire had already been raging for two days. Despite his obvious innocence and the fact that few people believed his confession, a scapegoat for the fire was urgently needed, and Hubert was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death at the courts of the Old Bailey. He was hanged at Tyburn, London on October 27, 1666. When his body was later handed by authorities to the Company of Barber-Surgeons for dissection, it was seized upon and brutally torn apart by an angry mob of baying Londoners.

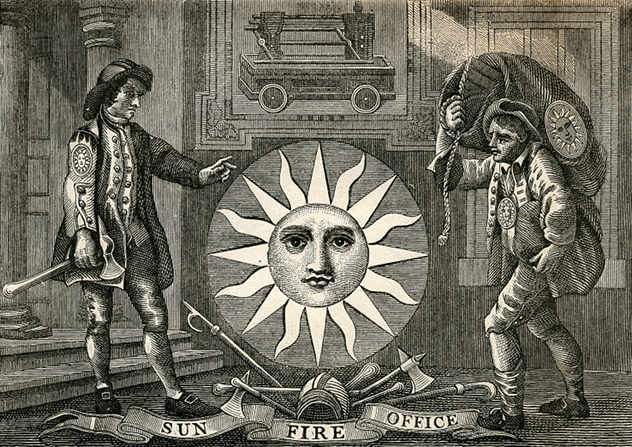

2The Fire Gave Birth to the Insurance Industry

The estimated value of the properties destroyed by the fire was £10 million (around £1.5 billion or US$1.9 billion in today’s money). The tenancy contracts of the time ensured that it was the tenants rather than the property owners who were responsible for the repairs and replacement of the houses. Tenants were even expected to pay rent while their burnt homes were being rebuilt. Reacting to demand, this all led to Nicholas Barbon setting up the “Fire Office,” the first insurance company, in 1680. This was soon followed by the establishment of other insurance companies, and by 1690, one in ten of London’s homes was insured against fire. By 1720, the number of insurance policies underwritten had reached 17,000 worth £10 million—the estimated cost of the damage caused by the fire.

1Bakers Apologized for the Fire—320 Years Later

In 1986, to mark the 500th anniversary of the granting of their Royal Charter by King Henry VII in 1486, John Copeman, Master of the Worshipful Company of Bakers, publicly unveiled a wall plaque at the corner of Pudding Lane and Monument Street, just feet from the site of Thomas Farriner’s bakery. The plaque finally acknowledged the fact that a fellow baker had been responsible for the start of the Great Fire of London, 320 years earlier. The Lord Mayor of London, Allen Davis, said in a simple response, “It’s never too late to apologize.” Gavin Elias is a forty-something-year-old male, living in a remote corner of Wales in the UK. He is always aloof.