During the decomposition process, the compost heap produces a considerable amount of heat, reaching around 66–82 degrees Celsius (150–180 °F). From culinary feats to matters of green energy, people have come up with imaginative ways to make the most of the heat from their compost heaps. We know that compost enriches our soil, but here are some other ways it can enrich our lives. So kick back, brew yourself a cuppa compost tea (don’t), and enjoy the ingenuity of some of our compost pioneers.

10 Make Your Own Dairy Products

In 1980, Jim McClarin had a breakthrough moment and compost cookery was born. Writing in Mother Earth News, McClarin described how he left his yogurt pail in his compost pile to keep it warm.[1] The next morning, he discovered that the heat produced by the compost had been higher than expected and a cheese curd had formed instead. Cheese and compost find common ground in their aromatic qualities. Sadly, McClarin did not elaborate any further on the compost-driven cheese-making process. Instead, he experimented with temperatures at different depths in his compost mound. He dug around to find the perfect temperature zone for compost yogurt, which became a regular part of his diet from then on.

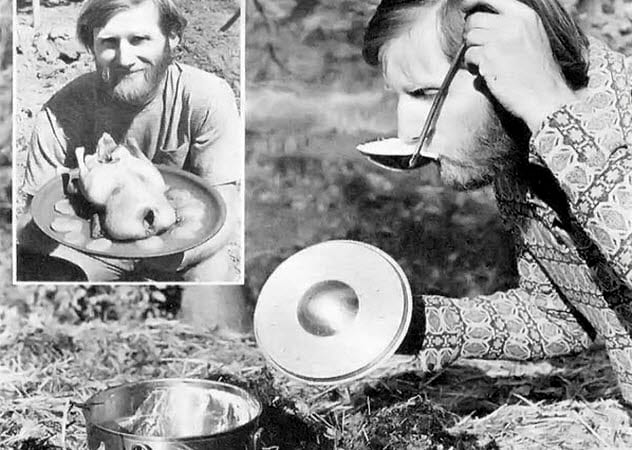

9 Hard-Boiling Eggs

According to the “half-buried mental note” of compost cookery trailblazer Jim McClarin, cooking eggs in compost may be an ancient Chinese practice. At this stage, though, the technique is untested enough to merit safety warnings. So we don’t recommend that you do it. But if you decide to try this at home anyway, wrap your food tightly and eat it with care. After all, this is cookery among a cocktail of decaying plants, food, and possibly manure. Unlike in the kitchen, cooking an egg in compost is a slow, inaccurate procedure.[2] Those who have tried it report cooking times ranging from 1 to 24 hours. McClarin suggests that you put your eggs in before bed so they’ll be ready for your breakfast the next morning. Ultimately, the process depends on the heat of your heap, which can fluctuate massively depending on what has been put on it and when. Compost cooking may be efficient in terms of energy use, but time is another matter. Although McClarin wrapped his egg in a plastic bag, others have just put the egg straight in. Personal experience here suggests that an egg wrapped in one layer of foil and tied up in a sandwich bag is still not enough. My egg looked beautiful, even silky. The yolk was the finest golden yellow. But the smell was too much to bear. In the end, all that I produced was a nice photograph.

8 Bake A Cake

A class of homeschooled children in Massachusetts successfully baked a lava cake in a mound of compost.[3] It took roughly a day. As we consider the diverse potential of the emerging art of compost cookery, this brings us hope. Not to take anything away from the kids here, but we should bear in mind that they did have access to a 6-meter (20 ft) compost pile. The cake itself was buried 0.6 meters (2 ft) deep. Overall, a 6-meter (20 ft) mound of compost is bound to produce and retain significantly more heat than most of us are likely to get in our own personal heaps.

7 Gourmet Cuisine

For years, the staff at the Highfields Center for Composting had tentatively experimented with heating cans of soup in their compost piles. But it took professional chef Suzanne Podhaizer of the former restaurant Salt to take this to the next level. Podhaizer successfully compost-cooked a branzino-and-scallop dish, served on a bed of well-cooked (though slightly squashed) rice. The resulting meal was described as “thoroughly cooked, earthy, and satisfying.”[4] Podhaizer made use of the center’s compost heap—or “worm parlor”—where the restaurant regularly sent their food scraps. They also used the compost to fertilize the plants in their kitchen garden. Here’s the beauty of Podhaizer’s dish: It was cooked with energy that was partially from Salt’s own leftovers, and then leftovers from her scallop dish were fed back into the system. Again, McClarin’s influence can be felt here. As his technique developed, he was able to cook full roast beef meals as well as duck with orange and apricot, served over a red wine and wild plum sauce. He never succeeded in cooking soft pinto beans, though.

6 A High-End Compost Restaurant

New York has been exploring a range of food waste initiatives and is undergoing what has been termed a composting “revolution.” The city’s department of sanitation has introduced a number of composting sites near subway stations as well as looked into the logistics of asking all restaurants and businesses to compost their food waste. According to Bon Appetit in 2013, a big New York restaurant took this one step further, planning to cook its dishes in the heat produced by composting. It remains unclear whether the restaurant succeeded. Due to legal reasons, presumably surrounding the sale of food cooked in compost, the restaurant was unable to be named. While it appears that the high-end compost restaurant never got off the ground, Bon Appetit pointed out that the temperature at the heart of a compost heap can be higher than a sous vide bath. Although there are obvious differences between a countertop water bath and a compost heap, it clearly has intriguing potential for high-end sustainable cuisine.[5]

5 Compost-Powered Showers

Proximity to your compost pile may not be preferable here, but many people have found ways to build shower systems using their compost. Some methods are as simple as coiling the majority of a length of hosepipe inside the heap and fitting a showerhead and stand to the other end. In this case, the effort of maintaining a compost heap outweighed the benefits of the warm shower it produced. Solar panels proved to be much more efficient and just as green. Permaculture teacher Darren Doherty was far more successful. By burying a 2-meter (7 ft) by 2-meter (7 ft) heating system in his compost and combining that with a solar heating system, he was able to produce up to 150 liters (40 gal) of hot water at one time.[6] On average, that’s roughly enough water for over 20 minutes of showering or two hot baths.

4 Harvest Methane

Direct contact with your compost may not be your cup of tea. Luckily, heat is not the only by-product of the composting process. When done right, compost also releases methane gas. This relies on maintaining a balance in the compost between acid-producing bacteria and the methane-producing bacteria that eats it. Methane is often harvested from landfills, which produce enough gas to power 8,500 local homes in some cases.[7] There are also examples of a number of farms, such as Green Mountain Dairy in Vermont, which are producing electricity for the grid from the methane released by manure. On a smaller scale, the Urban Farming Guys have built what they call a “methane biodigester.” Simply, this is comprised of one cylinder (or barrel) of compost with a smaller cylinder placed upside down on top of it. This serves to capture the methane released and to pressurize it. A pipe is attached to the methane chamber at one end and to a stove or generator at the other. With this model, methane is steadily produced for 7–8 weeks. This seems to offer the best of both worlds: cooking from the by-products of your compost without the inaccuracy (or residual smell) that comes from burying your food in it. Of course, there’s nothing stopping you from doing both at once.

3 Run Your Car

In the 1970s, Frenchman Jean Pain developed various ways to run the majority of his home from the energy produced by his compost heap. With the organic waste he produced from maintaining his woodlands, Pain fertilized what became “incredibly prolific gardens.” He also ran a compost water heating system—one that was capable of warming a 93-square-meter (1,000 ft2) home. On top of this, Pain developed his own air heating system. He buried heat ducts inside one of his compost piles, with entry and exit pipes that ran directly into a building. His ingenuity didn’t stop there. He also made use of a methane-harvesting tank and ran water cooling pipes around the outside of it to regulate its temperature. With this method, Pain was able to heat water for his house and productively collect methane from his compost heap.[8] This produced 1.4 cubic meters (50 ft3) of gas per day. From this, the Pain family was able to power the appliances in their house and run their Citroen 2CV truck, giving it enough fuel to drive 100 kilometers (62 mi).

2 Heat Your Swimming Pool

To loosely reimagine Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as a compost mound, we’re coming pretty near the top with this list. From the domestic success of Jean Pain, we must move firmly into the realm of life’s luxuries. So once you’ve had a nice, long, compost-heated shower and feasted on the scallops you’ve retrieved from your steaming heap, where do you go next? Gaelan Brown’s recent book, The Compost-Powered Water Heater, offers a practical introduction to DIY compost heating systems. Among others, one of Brown’s suggestions is to build a system that can heat your pool for free. Now, the idea of lounging by your perfectly warm, refreshing pool on a hot summer’s day need not be marred by a stinking pile of compost. Brown stresses that the compost heating system has the added benefit of reducing obnoxious odors. While a compost-powered hot tub might be out of the question here, a heated pool is still pretty luxurious.[9]

1 A Renewable Energy Source

Taking their influence from Jean Pain’s innovations, a number of groups have been exploring the wider potential of compost’s by-products as a renewable energy source. The University of Edinburgh’s School of Engineering developed a compost heat exchange which was capable of producing water at 60 degrees Celsius (140 °F). When they tested it against similar solar and ground source heating systems, the compost system provided the most reliable supply.[10] There is also the Compost Power Network, a not-for-profit organization that researches compost heat recovery and has collaborated on research projects with several universities. They have been developing Pain’s methods and are working on safe compost-based energy systems that make renewable energy possible in tandem with nourishing the land we live on. Ben likes chickpeas and lemon trees. He’s converting a food van.