Even if you don’t think they’re quite the lookers, you have to admit that the facts about them are captivating. These creatures are incredibly hardy and live almost everywhere you find water. And since the planet is mostly water, you won’t have to look very far. So let’s dive into why these minuscule animals are so astounding.

10 What the Heck Are They?

There are more than 1,100 species of these tiny invertebrates. Tardigrades are purported to be closely related to arthropods like crustaceans, spiders, and other insects. But their classification is still somewhat of a mystery due to their many unique attributes and because there is no way to directly correlate them to the arthropod family. It’s mostly their resemblance to some animals in this family that gives them this potential label. It’s very possible that they will end up representing something entirely new on the tree of life! At one time, they were believed to be more closely related to bacteria, but this was a misconception due to tainted samples, as proven by future research. In reality, they are multi-celled organisms that evolved from eukaryotic cells, which means that their genetic material is located in a central nucleus. Without getting all science-y, it simply means that they have more cells than bacteria, which have never grown to be more than one-celled organisms. It’s fairly obvious now that we can see them. Yay for advanced technology![1]

9 Little Body, Killer Teeth

Tardigrades belong to a special category of animals referred to as extremophiles. This simply means they can survive in conditions most other creatures can’t, including humans. They have a translucent body with an exoskeleton that consists of four segments and eight stubby legs with four teeny, tiny claws on each used to grab onto the surfaces from which they feed. Their heads are a well-defined fifth segment, even if they look a bit squished. They range in size from 0.5 to 1.2 millimeters (0.02 to 0.05 inches), but they usually do not grow larger than 1 millimeter. And admittedly, their mouths are slightly creepy looking. The mouth is round, can actually telescope outward like a spear, and is full of sharp teeth (called stylets) they use to pierce and then suck the liquid out of their meals. We’ll discuss their diets a little later, but they aren’t vampires like mosquitoes or spiders, at least not in the sense of enjoying blood. And thankfully, we aren’t on the menu either. At least not yet.[2]

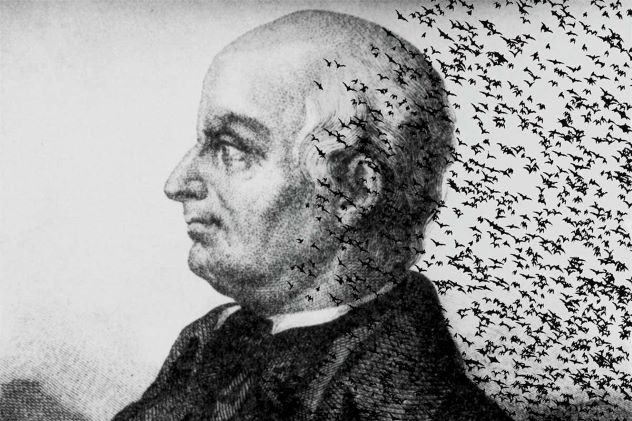

8 Been Around for Millenia

Despite only recently being studied in more depth, they were discovered back in 1773 by J.A.E. Goeze, a German pastor. Three years after that, they were given the name Tardigrada, “slow stepper,” by an Italian biologist named Lazarro Spallanzani. And recent studies have revealed that they have a much longer history than when people finally began recognizing their existence. Realistically they are probably one of the oldest terrestrial organisms out there. They’ve existed for an estimated five hundred million years or more. Who says humans are the most adapted to survive? Look at bacteria and other things invisible to the naked eye that have long predated the human race and thrive quite heartily still. It’s a pretty astonishing and magical world when you observe it outside of the limited scope of typical human mindsets. Put down the smartphone and go exploring…after you finish reading this, of course![3]

7 Desiccated and Frozen…but Alive

These little guys are most often found in water, especially fresh water. But they also live in every habitat on Earth where water is present, from Antarctica to the oceans to tropical rainforests to mountaintops and even in sand and soil. The easiest place to find and study them is in the water film found on mosses and lichens. So yes, you can likely find them in your own backyard, especially if you live near a body of freshwater! They are considered aquatic since they need water to live. The water around their bodies is necessary to allow gas exchange and prevent them from desiccation, basically being a sun-dried tomato or dehydrated fruit. But, if they are removed from the water, they don’t actually die. They can be reanimated once they are returned to that life-giving H2O. And that isn’t all! They can be frozen at extremely low temperatures for very long periods of time and still be reanimated once they thaw. How awesome is that? They’re getting cooler with every new thing we learn about them.[4]

6 A Fungi Diet

So what do they eat? Mainly they feast on mosses, flowering plants, bacterias, and lichens, or as they are more commonly known, fungi. They are also known to slurp on animal cells, and some of them are actually cannibals, eating other tardigrades. They suction out the fluids that are nutrient-rich after using that kind of disturbing mouth to puncture the cell walls and membranes of their targets. It’s a really good thing they don’t have a taste for us, or they wouldn’t be quite so cute anymore. Now just imagine, like a scientist, how many ways they have probably helped by devouring bacteria that could have caused more plagues or at least localized disease. They’re plump, little miracles swimming all around us. Mini, water-dwelling angels![5]

5 Extreme Survival

Let’s learn a little more about that remarkable ability to come back to life that has made the scientific world so keen to study them further. Through a process known as cryptobiosis, they are able to slow their metabolic rate to as low as 0.01 percent, essentially making it possible for them to survive without eating. Their organs are protected by a sugary gel that continues to produce a large amount of antioxidants. On the occasions that they are exposed to extremely low temperatures or dehydrated, they form something called a tun. They curl into a tiny ball by tucking in their head and hind legs. And in freezing conditions, they can also somehow prevent the growth of ice crystals. There’s no way science is finished studying that ability. And if the water they live in has lower than normal oxygen levels, the tardigrades can stretch out, slow their metabolic rates, and absorb oxygen through their muscles. As if all of this isn’t incredible enough, they can produce a protein that protects their DNA from radiation damage. They can also survive some noxious chemicals, low-pressure vacuums, boiling alcohol, high pressure such as deep ocean depths, and changes in water salinity. It’s becoming less of a wonder how they have survived so many mass extinctions over time![6]

4 Brace for Impact

Water bears aren’t entirely indestructible or immortal despite their many shocking survival capabilities. It may seem that way, but they do have some weaknesses and will eventually die. One thing they definitely cannot survive is human stomach acid, which is a good thing because you’ve almost certainly drunk some in your lifetime without knowing. And their natural life span, without being frozen or desiccated, is about two and half years. And they can’t survive an impact in excess of 3,218 kph (2,000 mph). Yeah, people shot them out of guns to test the limits of their survival skills. Humans are so weird. Recently it has been discovered that their life spans are greatly shortened in water temperatures of 38°C (100°F) or more. Climate change may be just as much of a detriment to them as it is to all other forms of life. We truly need to get better control of our habits that are speeding up that process for all of our sakes. Let’s save the bacteria-destroying water angel moss piglet! New campaign?[7]

3 Walk This Way

Watch them walk! The videos are out there now, and it is precious. When they are not swimming, tardigrades lumber along on those eight little legs in search of moss and mushrooms to suck dry. And they have the gait of insects 500,000 times larger than them and even crustaceans. It looks surprisingly similar to galloping. They just do it very, very slowly. Ever feel like a tardigrade without your morning coffee? Watch this video on YouTube They are aquatic. Hence, water angels (hoping that catches on)! So, of course, they also swim. They do this with those miniature legs too. And they can swim a bit more quickly than they walk. They also float, but it is usually on bits of debris instead of free-floating. So their float seems a bit more like surfing. They’d probably kill the competition at the Pipeline in Oahu, Hawaii.[8]

2 Males Need Not Be Present

The Moss Piglets have some interesting reproduction practices too. Some species even reproduce asexually. The female lays the eggs, and they develop on their own with no need for external fertilization. Clean and efficient (but maybe not as fun). It also eliminates the need for any males in the species (um…wait a minute there). If you’re a fan of science fiction or horror films, watch No Men Beyond This Point, and you’ll see what might happen if people went the way of the self-reproducing tardigrade! Watch this video on YouTube In some species that have been observed mating, the lady lays anywhere from one to thirty eggs. But the eggs are implanted in the molting cuticle of her skin. Once the guy comes along, he wraps around her, and they work toward stimulation together, sometimes for an hour or more. The male then releases the sperm under her skin. In other species, the female sheds the cuticle completely and lays the eggs in it. The male comes along later to fertilize the eggs. The eggs take around 40 days to develop and sometimes 90 days if they have been desiccated. So it’s not the most romantic process.[9]

1 Tiny Alien?

Because of their multitude of strange and death-defying attributes, there’s a belief spreading that the tardigrades are aliens that arrived here on a meteor. This is probably more science fiction than fact. But that didn’t stop people from turning them into aliens. We sent them to the moon after all, if only by accident. Poor little water angels. An Israeli spacecraft was carrying thousands of tardigrades in an effort to study their survival capabilities in the vacuum of space and the various forms of radiation. But it crashed and landed on the moon. The water bears were in a “hibernation” state and encased in artificial amber. And it is firmly believed by the program’s director that the moss piglets very likely survived and are still in their suspended animation state. Now the tardigrades are astronauts too. Truly fascinating.[10]