Additional finds also unravel the deeper nuances of the civilization. They provide glimpses at challenges, unexpected connections, and tantalizing clues to mysteries.

10 The Sandstone Sphinx

Near the town of Aswan stands an old temple. Called Kom Ombo, it has been the subject of study for years. In 2018, archaeologists had to drain groundwater from the pharaonic ruins. During the process, an enigmatic statue rose into view—a sandstone sphinx. Compared to the more famous one at Giza, the 38-centimeter-high (15 in) creature was a miniature. Nevertheless, the discovery was remarkable. It added more flavor to the temple’s past and, despite thousands of years, was in mint condition. Two months before the statue made its appearance, two sandstone reliefs showing King Ptolemy V were found in the same part of the building. This placed the sphinx in the Ptolemaic dynasty (305–30 BC), although its purpose remains unknown. Sphinxes were important. Sometimes, they were used as tomb guardians, and they often depicted the face of a real pharaoh. Archaeologists are fervently hoping that the sandstone sphinx is a portrait of one of the royal Ptolemies. If future studies can confirm this, the statue’s remarkably undamaged facial features could provide a direct glimpse at a lost pharaoh.[1]

9 Massive Ritual Structure

Founded around 3100 BC, the ancient Egyptian city of Memphis is located around 20 kilometers (12 mi) south of modern-day Cairo. It was the home of King Menes, who merged Upper and Lower Egypt into a single, powerful entity. Part of Memphis can be found in the modern-day town of Mit Rahina. In 2018, archaeologists worked at Mit Rahina when they unearthed something remarkable. Though a little shy on the details, the find was described to the press as a massive building that was most likely a residential block occupied during the time of Memphis. In addition to the Egyptian building, the team also found another attached to the block. However, the second structure was not entirely native. It contained a big Roman bath and a room. According to the archaeologists, the chamber was most probably used for religious ceremonies.[2]

8 A Priest Graveyard

The site of Tuna el-Gebel is no stranger to ancient discoveries. This makes the 2018 appearance of a large cemetery even more amazing. The subterranean graveyard was 2,300 years old and west of the Nile River. Experts estimate it could take five years to fully excavate all the burial shafts. Thus far, 40 sarcophagi, or stone coffins, were recovered and many contained priests. This particular group worshiped the god Thoth, said to have brought the skill of writing to mankind. The mummified remains of one man suggested that he was a high priest. Inside the richly packed coffin, one item stood out. He wore an amulet with writing. Once deciphered, the hieroglyphics translated into a quirky-sounding “Happy New Year.” Apart from a vast collection of ceramics, jewelry, and charms, the graveyard also yielded more than 1,000 shabti statues. These tiny figures are believed to be the helpers of the dead, doing the deceased’s career duties in the afterlife.[3]

7 The Dakhleh Cases

At Dakhleh Oasis rests the remains of 1,087 ancient Egyptians. When researchers investigated the bodies in 2018, six cases showed cancer. They included a child with leukemia, a man with rectal tumors, and several others who might have contracted the cancer-causing human papillomavirus (HPV). Although cancer is nothing new—even HPV developed before humans—it was interesting to compare notes. Similar to today, HPV is prevalent in young adults in their twenties and thirties. This was also the case at the oasis cemetery. Though the disease could not be genetically confirmed, the age group and bone lesions suggested that HPV behaved the same among ancient populations. Statistics also suggested that the chances of developing cancer today in Western societies was around 100 times more than when these individuals were buried (3,000–1,500 years ago). Nothing in the culture’s vast records proves that ancient Egyptians had a solid concept of cancer. They probably knew something was terribly wrong but had no specific treatment other than caring for visible symptoms, such as skin ulcers and pain.[4]

6 The Striped Sock

This ancient artifact looks like it was knitted a week ago. Complete with stripes that remain popular today, this sock once belonged to an Egyptian child. It was woven around AD 300, which was also about the time that somebody no longer had any use for it. (The sock was found in an ancient rubbish dump.) However, to the British Museum, it was incredibly precious. Experts wanted to dive into the dye and weaving techniques used to make the garment. However, all available techniques demanded destruction of a section or the whole sock. Only in 2018 did the museum pioneer an imaging tool that was noninvasive. Using the scan, they found that the stripes’ colors came from three natural dyes. Madder was used for producing red, woad for blue, and weld for yellow. The scan also gave a good preliminary understanding of the weaving techniques used. The obsession with this tiny sock’s manufacturing secrets may seem odd, but there is a reason. Ancient Egyptians are considered to be the ones who invented the knitted sock, and the infant’s garment could shed more light on their craft.[5]

5 Village With Silos

Long before the pharaohs and the construction of the pyramids, a village stood along Egypt’s Nile River. Discovered in 2018, it turned out to be one of the most ancient ever to resurface on the Nile Delta. The age of the village is just one remarkable thing. Apart from beating the invention of Egyptian royalty and pyramids, the nameless location also existed over 2,000 years before somebody scratched the first hieroglyphics. The 7,000-year-old settlement also yielded ruins that included the remains of deep storage silos. They contained a massive number of plants and animal bones. Finding out more about these scraps could lead to the understanding of how farming developed in Egypt. With this village situated around 140 kilometers (87 mi) north of modern-day Cairo, a mystery surrounds the reason why the site was ultimately abandoned. The village clearly enjoyed successful habitation for almost 2,000 years but emptied around two centuries after Egypt was unified by an unknown pharaoh.[6]

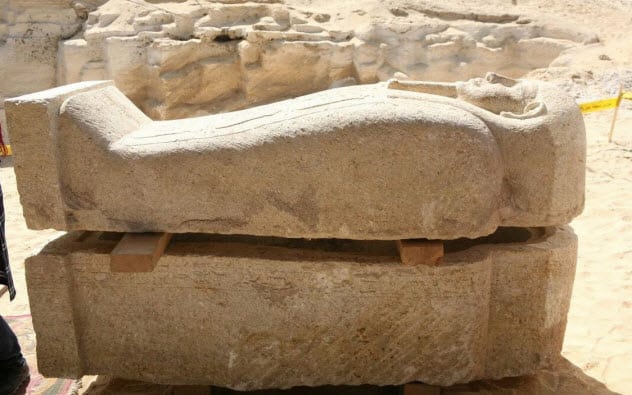

4 The Black Sarcophagus

In 2018, a black granite sarcophagus hit the news big-time. Found in Alexandria, it weighed 30 tons and required help from the Egyptian military to remove its lid. Scholars thought that they would find an important individual, possibly even Alexander the Great. However, three mummies inside drifted in a mysterious red goop. The latter turned out to be modern sewage water that had destroyed and mixed with mummy parts. The next guess suggested that the trio were soldiers. One skull showed arrow wounds, and there were no elite grave goods. The military officer theory crashed when one body turned out to be a young woman. With the exception of royal leaders, women were not a part of the ancient Egyptian military. All the bodies dated to the early Ptolemaic period, which began in 323 BC. They appeared to have been buried at different times. One man showed signs of having survived trepanation (ancient skull surgery). This is a rare sight among Egyptian remains. The mystery surrounding the identities of the three mummies has not yet been solved.[7]

3 The Lost Oasis

The site of Bir Umm Tineidba, which was found in the Egyptian desert of Elkab, was once thought to be an archaeological blank. Yale researchers arrived in 2018 with cutting-edge technology, and the story changed. Bir Umm Tineidba was once an ancient hub where people left graffiti, art, tombs, and buildings. The rock art dated to an age before hieroglyphics (about 3300 BC) and showed exceptional examples of early Egyptian drawings. The images resembled those from the Nile Valley, suggesting that the two populations had mixed. The possible discovery of hybrid groups could change how archaeologists view Egypt’s evolution into a state. Among several burial mounds, the most noteworthy belonged to a young Egyptian woman. Her elite grave goods showed that the site also had connections with the Red Sea region. To the south of the rock art and graves stood an unknown Roman settlement. Consisting of over a dozen ruins, it dated to AD 400–600. Its presence also filled in another blank in the region. But this time, it was about similar Roman sites in the desert. More studies at Bir Umm Tineidba also promise to reveal more on how the region transitioned from the Late Antique to the Early Islamic Period.[8]

2 Unraveling Mummification Mystery

Experts know a lot about the ancient Egyptians. However, nobody alive today knows how to turn somebody into a mummy. In 2018, scholars caught a big break. At the Saqqara necropolis in the Nile Delta, excavations unearthed an embalming workshop. Five mummies were inside the workshop, and an additional 35 were found in an adjoining burial shaft. Those in the shaft dated from 664–404 BC. They revealed that mummification was not a social equalizer. The elite got better treatment. But it was the tools left behind in the workshop that caused the most excitement. Researchers already know that embalming took 70 days, starting with washing the body, removing the organs, and drying the corpse in salt for 40 days. Before being wrapped in linen, the body was treated with oils.[9] The type, quantity, and order in which the oils were used is where modern understanding of mummification hits the wall. Incredibly, the workshop had labeled measuring cups with the mysterious oils. Future chemical testing will identify exactly what substances were used and perhaps help solve the mystery of the process.

1 Pits With Severed Hands

Not every ancient Egyptian find is a golden mask or a beautifully painted mural. Sometimes, discoveries are downright gruesome. In 2017, Egyptologists working at royal ruins in Avaris found four pits, two of which were located in what some believe was once the throne room. Together, the shafts contained 16 human hands chopped off 3,600 years ago. The entire batch consisted of right hands, and their exceptionally large sizes showed that the victims were all men. The creepy sight confirmed a practice already seen in hieroglyphics—hacking off an undesirable party’s hand in exchange for a reward. Experts believe that Egyptian noblemen “bought” enemy hands from their own soldiers with gold and then ritually buried the body parts. Though it is hard to say to whom the hands belonged, a strong clue is the historical level in which they were found. It dated back to the time when the Egyptian army finally expelled the Hyksos, a foreign nation that conquered Egypt in 1650 BC. If not Hyksos hands, the horrific amputations might have been punishment for Egyptian soldiers who revolted while fighting the Hyksos.[10] Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages