Sound familiar? It’s the motto of the United States Postal Service, right? Actually, the USPS has no motto, but this quotation from Book 8 of The Persian Wars, by Herodotus, which is inscribed on the General Post Office in New York City, is a fair evaluation of the lengths to which postal carriers have gone – and still go – to get our mail to us.

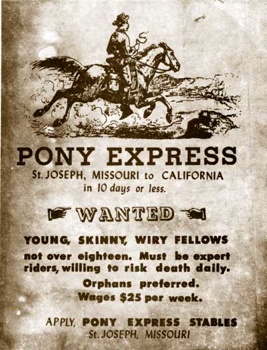

In 1860, William H. Russell was sure that his Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express Company could beat the time of stagecoach wagons, which made the trip from Missouri to California in 24 days. The company built way stations every 10-15 miles, and published the following advertisement: Wanted: Young, skinny, wiry fellows not over 18. Must be expert riders, willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred. Wages, $25.00 per week. Johnny Fry and Sam Hamilton were first to sign up, signing an oath under which they swore not to cuss, fight, abuse animals, or lie. The Pony Express was born to great expectations. “No danger or difficulty must check his speed or change his route, for the world is waiting for the news he shall fetch and carry… God speed to the pony and the boy!” (The Western Journal of Commerce: Kansas City.) Russell’s prediction proved accurate: the first run was completed in 10 days – less than half the stage time. Riders covered 75-100 miles each day, stopping at the way stations only long enough to change horses. Sending a letter on the Pony Express was not cheap: $5.00 for 1/2 oz., compared to standard U.S. postage, which was 10¢. But if you were in a hurry, there was no better choice. In 1861, President Lincoln’s inaugural address made the fastest transcontinental trip up until that time: St. Joseph, Missouri to Sacramento, California in 7 days, 17 hours. But that same year, the transcontinental telegraph was completed, and on October 26, 1861, the Pony Express came to an end after just eighteen months of operation.

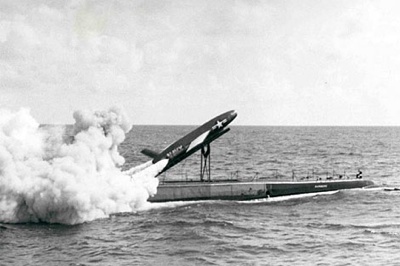

Mail has been delivered by horse, boat, sled, snowshoes, skis, trucks, motorcycles, automobiles, mules, pole boats, airplanes, hovercraft, dog sleds, parachutes, and snowmobiles. But none is stranger than missile mail. In 1936, two rockets transported mail about 2000 feet across a frozen lake toward Hewitt, New Jersey, from Greenwood Lake, New York. The rockets crash-landed and slid across the ice. The Hewitt postmaster walked onto the ice and dragged the mail bags the rest of the way. Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield later attempted again to shoot the mail. On June 8, 1959, Summerfield declared, “Before man reaches the moon, mail will be delivered within hours from New York to California, to England, to India, or to Australia by guided missiles.” The submarine USS Barbero fired a guided missile with 3000 letters toward the naval air station in Mayport, Florida. The missile, at 600 mph, covered the 100 miles in 22 minutes. The cost, however, was too great to justify missiles as a standard method of mail delivery.

In Supai, Arizona, a sign in the local café reads, “No fries til mail.” The town of Supai eats more mail than it reads. At the bottom of the south rim of the Grand Canyon, and home to 525 Havasupai Native Americans, Supai is the last place in the United States to get its mail by mule train delivery. Helicopters and air drops are impractical here, so the 3-5-hour trip is made by mule five days a week, with each mule carrying up to 200 lbs. of mailed supplies.

When New York jeweler, Harry Winston, decided to donate the fabled Hope Diamond to the Smithsonian Institution, he chose first class mail. “It’s the safest way to mail gems,” Winston was quoted as saying. The delivery from New York City to Washington, D.C., cost Winston $2.44 in postage, and an additional $142.85 for a million dollars’ worth of insurance. Letter carrier James Todd picked up the diamond at City Post Office and drove to the Natural History building, where he delivered it to the curator. Afterward, Todd told the Washington Post that he felt “a little shaky,” not because of the enormous value of the 45.52 carat diamond, but because he was not used to getting so much attention at his job.

In December, 1954, the postmaster in Orlando, Florida, received the following letter: On December 7, 1954, David received the following response:

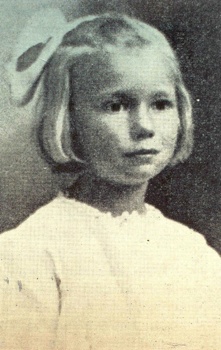

In 1914, a four-year-old named May Pierstorff, who lived with her parents in Grangevillle, Idaho, was going to visit her grandmother in Lewiston. Her parents calculated that Parcel Post was cheaper than full fare. At 48.5 lbs., the child came in under the weight requirement of less than 50 lbs. It was then legal, and still is today, to mail chickens, so her parents were charged postage at the chicken rate. The Pierstorffs pinned the fifty-three cents in postage to her coat and put May in the baggage car, under the care of the postal clerk. Though it was customary to leave packages in the post office overnight, when May arrived in Lewiston, the postmaster took her to her grandmother. By 1920, it was illegal to mail human beings, although not before an angry mother mailed a baby to the husband who had left her.

The pneumatic tube systems represented a different kind of tunnel vision. Under New York City, workers still occasional encounter remnants of what was once a flourishing underground mail delivery system. Powered by positive rotary blowers and reciprocating air compressors, pneumatic mail tubes could fly under the city at a rate of 100 mph, regardless of snow or traffic snarls overhead. At one time there were 136 operators in New York City, called rocketeers. They could send one tube every 12 seconds. By the 1950s, 55% of NYC mail was send by tubes. There were problems, however, Each container could hold only five pounds, and could not carry more than one kind of mail. The process was expensive, partly because each container needed to be sorted twice. The time saved in shooting the mail through the tubes was lost in sorting and resorting. The system was suspended from 1919-1922, briefly resurrected in New York and Boston, and finally discontinued in 1953.

Rural Free Delivery, RFD, was born when Postmaster General John Wanamaker thought it made more sense for one person to deliver mail to country homes that for fifty people to go to town for their mail. Until that time, postmasters would often hire a boy to deliver; schoolteachers sent the mail home with their students, and the post office stayed open for one hour after church on Sunday, but none of these systems seemed satisfactory. The problem with delivery to country homes was, of course, mailboxes. Soon the roadsides were “littered” with orange crates, lard cans, feed boxes, and many other contrivances to hold mail. By 1901, Congress went into action, deciding after prolonged debate that country mailboxes needed to be of a standard size, have a signal flag to show when mail was inside, and be of a height and proximity to the road to be convenient for the mail carrier. The standard basic mailbox cost fifty cents, but there were some locked boxes that cost several dollars. As a result of this expense, some customers refused to buy a mailbox, and the post office refused to deliver their mail, resulting in some contentious exchanges. When Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward began sending out large catalogs each year, they hit upon a retailing gold mine. But the mailboxes needed to be resized, and in the 1920s, Congress approved the larger mailboxes still in use today.

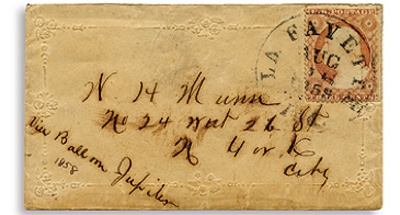

History’s first airmail flight happened in 1859, aboard the hot air balloon, Jupiter. The historic flight took place on August 17, with the temperature in the 90s. John Wise, the aeronaut, was given 123 letters in Lafayette, Indiana, to deliver to New York City. The balloon had to ascend to 14,000 feet to pick up any wind, but that wind, unfortunately, carried it south. After covering only 30 miles in five hours, Wise descended in Crawfordsville, Indiana, where his trip was labeled a “trans-county-nental” flight. Wise gave the mail to a postal agent, who put it on a train for New York.

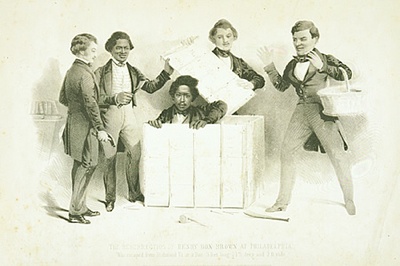

Henry “Box” Brown, a slave who had seen his wife and children sold away from him, mailed himself to freedom on March 29, 1849. With the help of a storekeeper in Louisa County, Virginia, Brown had himself packed into a crate that was 3’x 2’x 2.6’ and labeled “This Side Up With Care,” to be sent to the home of Philadelphia abolitionist James Miller McKim. At 5’8” and weighing 200 lbs, Brown curled himself into the box with only a small container of water and traveled in that position for 27 hours. The crate was loaded onto a wagon, then to the baggage car of a train, then another wagon, then a steamboat, then another wagon, then a second baggage car, then a ferry, then a third railroad car, and finally a wagon that delivered him to McKim’s house. When no sound was heard from the box delivered to his house, McKim asked, “Is all right within?” and Brown answered, “All right.” When the box was opened, Brown stood up, and passed out. Public outrage at his story led to the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which made it illegal to help escaping slaves. When the law was passed, Brown moved to England, where he remained until 1875.